Tariff follies

Our new emperor has a well-advertised love of tariffs. They appeal to his grandiosity, as dramatic imperial gestures that will bring the world to heel at no cost to Americans, given his stubborn delusion that foreigners, not consumers, pay the duties. Should he carry through with his threats to slap 10%, 20%, 30%, tariffs on imports—many of them on products that aren’t even made here, so there aren’t any domestic substitutes—prices will rise significantly, quite the turn for a guy who ran against Bidenflation.

I’ve written about Trump’s tariffs for Jacobin, notably their regressive effects, hitting the poor far harder than the rich, while doing nothing to stimulate domestic production, their intended purpose. (Between March 2018, when the tariffs were imposed, and January 2021, when Trump left office, steel production fell by 6%, almost twice as much as overall manufacturing.) All important, but now I’d like to take a quick look at tariffs in American economic history.

In his Truth Social post announcing the creation of an “External Revenue Service” (ERS), Trump made some outlandish claims. It will, as he put it, demonstrating his idiosyncratic understanding of trade (and strange capitalization practices), “collect our Tariffs, Duties, and all Revenue that come from Foreign sources. We will begin charging those that make money off of us with Trade….” Trade can be beneficial to both parties, though he makes it sound like a purely exploitative relation. And almost no one aside from him and his circle of advisers thinks that foreigners, rather than US consumers, pay tariffs,. But let’s set these issues aside for now.

Instead, let’s look at tariffs over the long sweep of history. According to a useful factsheet from the Congressional Research Service, tariffs were an easy way to collect revenues in the early history of the country, which didn’t have a developed administrative structure. There were only so many ships docking in so many harbors to unload goods. So, taxing that merchandise was not much of a technical challenge. The government was small and didn’t need that much revenue anyway.

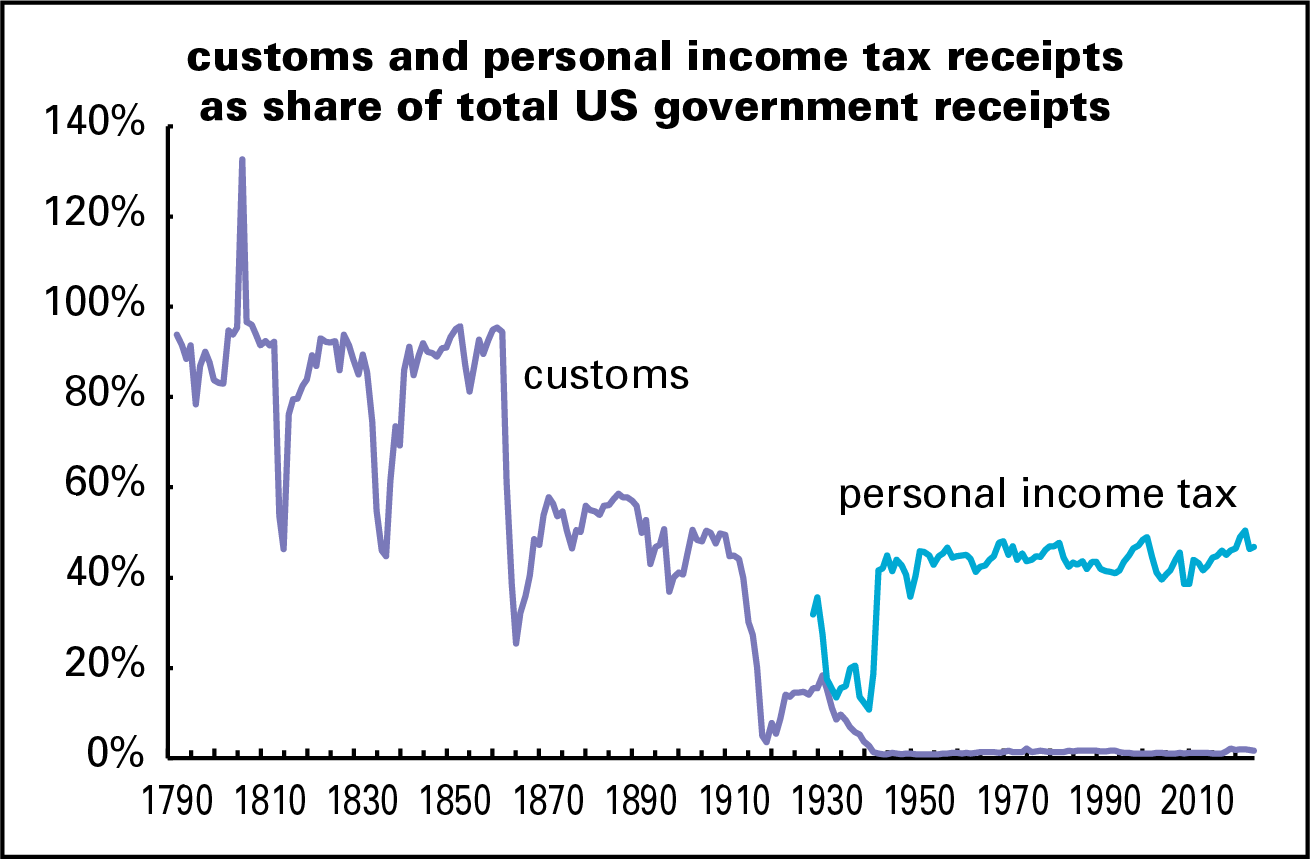

And government was small. From 1792 to 1930, federal revenue averaged less than 3% of GDP. (See graph above.) Obviously those old GDP figures are guesses, but let’s take them as a decent approximation of reality. From 1792 to the eve of the Civil War, 1860, tariffs provided an average of 86% of total federal revenue. There were some bumps before the Civil War, notably the War of 1812, which juiced expenditures and savaged imports. Besides borrowing heavily, the federal government increased excise taxes, reducing dependence on tariffs and leaving them accounting for just over half of federal revenues in the last third of the 19th century. With the introduction of the personal income tax (PIT) in 1913, tariffs receded in importance; since 1945, the PIT has accounted for 45% of federal revenues. (See graph below.)

(Speaking of federal revenues, the popular notion that taxation has been growing like topsy can’t survive fact-checking. As the graph shows, federal revenue as a share of GDP has been nearly flat for the last seven decades; in fact, the 2024 share, 17.1%, is below the 1951 share, 18.4%.)

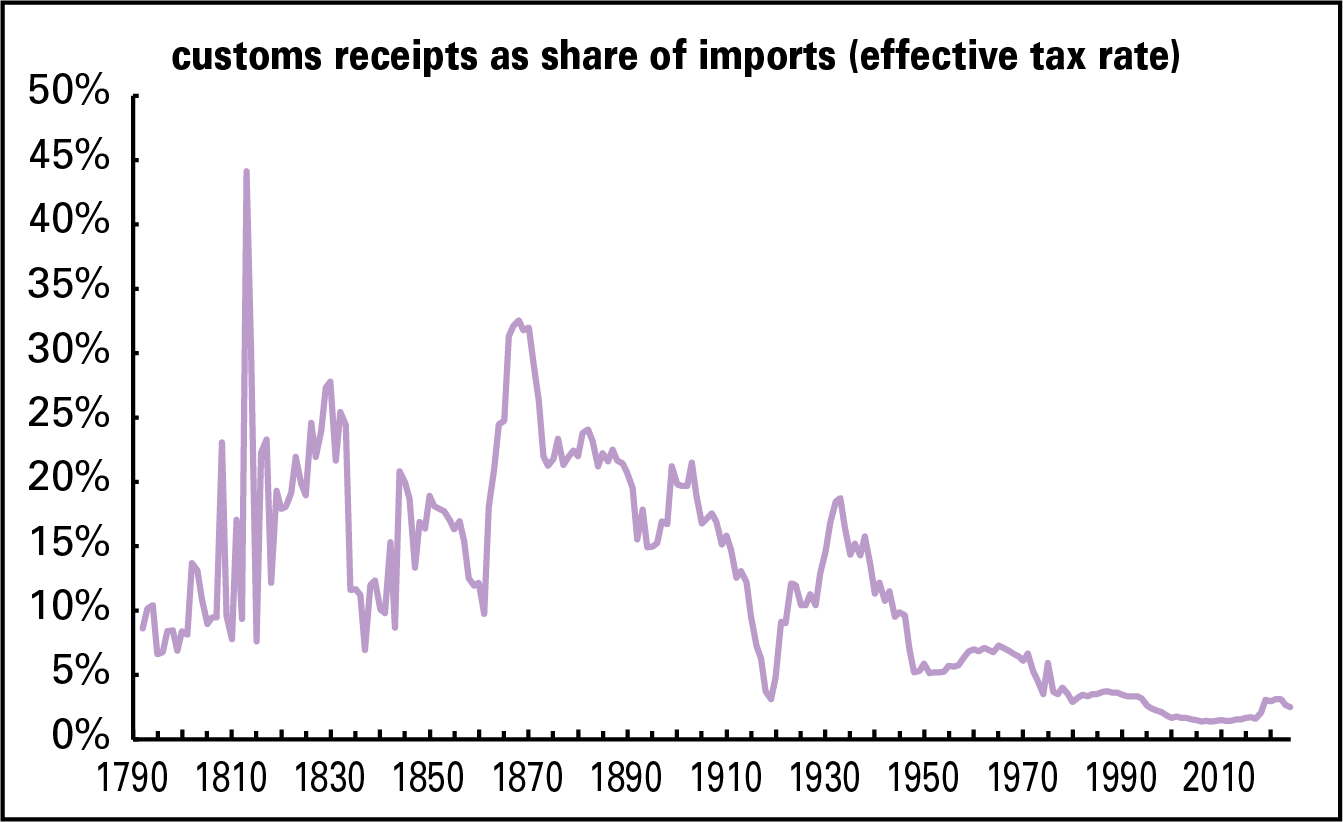

With the growth of the PIT, and federal revenues generally, tariffs (or customs duties, to use the technical term) have largely disappeared as source of federal revenue. In the graph above you can see a spike around 1930, the time of the infamous Smoot-Hawley Tariff, which many, though not all, economists believe contributed to the Great Depression. Customs receipts barely cracked 1% of total revenue in the 1990s and 2000s. With the tariffs imposed during the first Trump administration, and preserved by Biden, that share doubled to an average of 2.0% from 2019 to 2022, but they eased back to 1.6% in 2024. The effective tax rate—customs receipts as a share of goods imports, graphed below—follows a similar trajectory: high in the 19th century, lower in the early 20th, and low and mostly declining since the end of World War II. That looks poised to change.

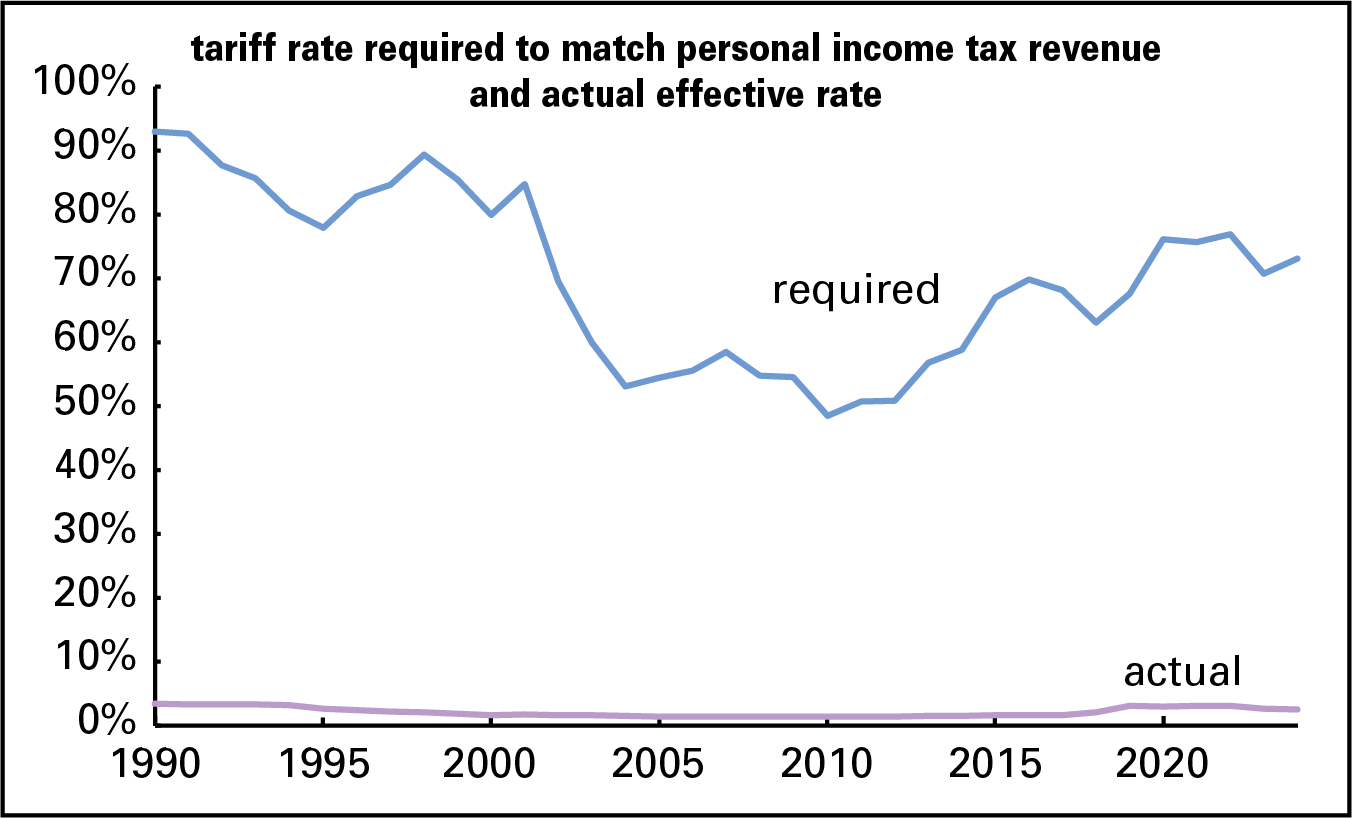

Since Trump has floated the idea of replacing the PIT with tariffs—switching from “taxing our Great People using the Internal Revenue Service,” as he said in the Truth Social announcement of the ERS—it’s interesting to experiment with how large those tariffs would have to be to plug the revenue gap. In the first three quarters of 2024, goods imports were $3.3 trillion at an annual rate, and the PIT brought in $2.5 trillion. Matching that would require a tariff rate of 70%. (Graph below.) The effective tariff rate last year—revenues divided by the value of goods imports—was under 3%.

Obviously a 70% tariff would decimate imports, but we’re not even considering that. And more than trivial increases would prompt retaliation from our trading partners, dinging US exports—and crafted to hit Trump-supporting regions especially.

It all seems like a stretch.