Fresh audio product: Trump, Israeli public opinion, the meaning of Ukraine

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

November 7, 2024 DH comments on the Trump victory, especially the role of inflation • Dahlia Scheindlin on Israeli public opinion • James Foley and Vladimir Unkovski-Korica, authors of this article, on the role of Ukraine in the Western political imagination

Fresh audio product: right’s war on an Idaho college, Israel’s goals

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

October 31, 2024 Laura Jedeed, author of this article, on the right’s war on North Idaho College • Mouin Rabbani on what’s driving Israel’s multiple wars, and on the state of the Axis of Resistance

Fresh audio product: arming and funding Israel, how people actually like their jobs

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

October 24, 2024 William Hartung, co-author of this paper, on how much aid the US has given to Israel over the last year (plus some wacky stuff on AI weapons) • sociologist Scott Schieman on his surprising research showing that people actually like their jobs

Anatol Lieven on the Biden/Harris grand design

This is the lightly edited transcript of an interview I did with Anatol Lieven on Behind the News, October 17, 2024. The audio is here.

My introduction to the segment:

Joe Biden’s foreign policy has been consistently and impressively bellicose, aggressively supporting wars in Ukraine and the Middle East and amping up tensions with China. And his anointed successor, who has something like a 50-50 chance of succeeding him, looks to be following suit. Many people have read Kamala Harris’s courting of endorsements from the Cheneys—the Liz and Dick of our times—as mere pragmatic electioneering, but they’re far from the only neocons to endorse her. Over a hundred former Republican foreign policy officials, including the odious John Negroponte, who had a hand in running Reagan’s wars in Central America in the 1980s, and George W’s CIA director Michael Hayden, who did a lot of warrantless wiretapping while he ran the National Security Agency, signed a letter endorsing her last month, out of concern that Trump would be a poor empire manager. So too has Bush’s Attorney General Alberto Gonzales, who provided legal opinions that justified torture. As Aida Chavez noted in The Intercept, “A section from the 2020 [Democratic] platform on ending forever wars and opposing regime change was completely removed in 2024.” The people who brought you the Iraq war are back.

These endorsements have been applauded by lots of liberals as a political victory for Harris, but the policy implications are alarming. But it is a return home for the neocons, many of whom were Democrats, a party that gave us the CIA, NATO, and the Vietnam War.

Here’s Behind the News regular Anatol Lieven to make sense of it all. Anatol is the director of the Eurasia Program at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft. In the 1980s and 1990s, Anatol covered the former Soviet Union, Eastern Europe and the wars in Afghanistan, Chechnya, and the southern Caucasus, for the Financial Times and the Times of London

I want to talk about each of the hotspots in the world in turn, but I want to start with a general discussion. The Biden administration’s foreign policy seems extremely bellicose and sometimes surprises me how bellicose it is. Is it like a wounded animal just striking out or is there some greater logic behind this? What is the strategy that is fueling this appetite for multiple wars and confrontations?

Basically, the whole of the American foreign and security establishment and the greater part of the political establishment, not all. I mean, there are dissidents on the right and left, essentially signed up to what used to be called the Wolfowitz Doctrine from the memo of 1992, which set out that the US should pursue and enforce permanent hegemony, not just in the world as a whole, but in every region of the world. This, as wise people pointed out at the time, meant that the US would inevitably come into conflict with a range of other states around the world who were never going to be prepared to allow the United States to dominate them and their regions in this way, because the Wolfowitz doctrine also said two things. It said that no state would have any influence beyond its borders, except that which was in the interests of the United States and allowed by the United States.

And it also said that the US had the right and indeed the duty to change the internal policies and systems other states in accordance with its wishes. And as some people pointed out at the time, this was basically an attempt to extend a hard version of the Monroe Doctrine. In other words, not a defensive version, but an interventionist version to the whole planet. And yes, I mean this was bound to lead to tension and even conflict wherever major countries had interests, vital interests, differing from those of the United States. But by a strange process of intellectual and cultural transformation, but with deep roots in American history, this has effectively become the ruling doctrine of both American political parties because it’s the ruling doctrine of the foreign security elites on whom they draw for their senior officials.

Thirty-two years ago, the US had more standing in the world, more economic standing, more cultural standing, more political standing than it does now. It was impossibly insanely grandiose back then, but it seems even more so now.

Well, I think that’s right, and oddly enough, two things have come together. One is that the very, very brief in historical terms, unipolar moment from the end of the Cold War to when Iraq started going badly wrong—or the financial recession of 2008—in any case, less than 20 years, has been now taken as the norm from which everything else is an illegitimate and strange and unacceptable divergence so that the US dominating everywhere is the norm. And if Russia tries to assert that it has always had vital interests in what happens in Ukraine that is evil and illegitimate and must be resisted. But at the same time, of course, yes, I mean the American elites are aware that the United States has a much smaller share of world GDP, as does the West in general, than it did 30 years ago, that China is now a superpower in its own right, that as we saw in the rejection of sanctions against Russia, most of the world, even countries that want good relations with the US like India, will not follow American orders.

And so, to the megalomania has been added an element of hysteria, of fear, of fear that America is losing this globally dominant position. And that seems simply psychologically unacceptable to the American Establishment. The idea that America could step back, make compromises, allow, seek cooperation with other major powers, recognize elements of their vital interests, they just don’t seem able to do that. Obviously, the Trump administration couldn’t do it, but leading elements of the Obama administration—not I think Obama himself, but obviously people like Hillary Clinton and Victoria Nuland—they couldn’t do it. And Antony Blinken and Jake Sullivan certainly can’t do it.

What is behind this? You said that it’s the foreign policy establishment. Is it a matter of personnel? Are there interest groups driving this? Is it too cynical to point out that arms dealers are rolling in money?

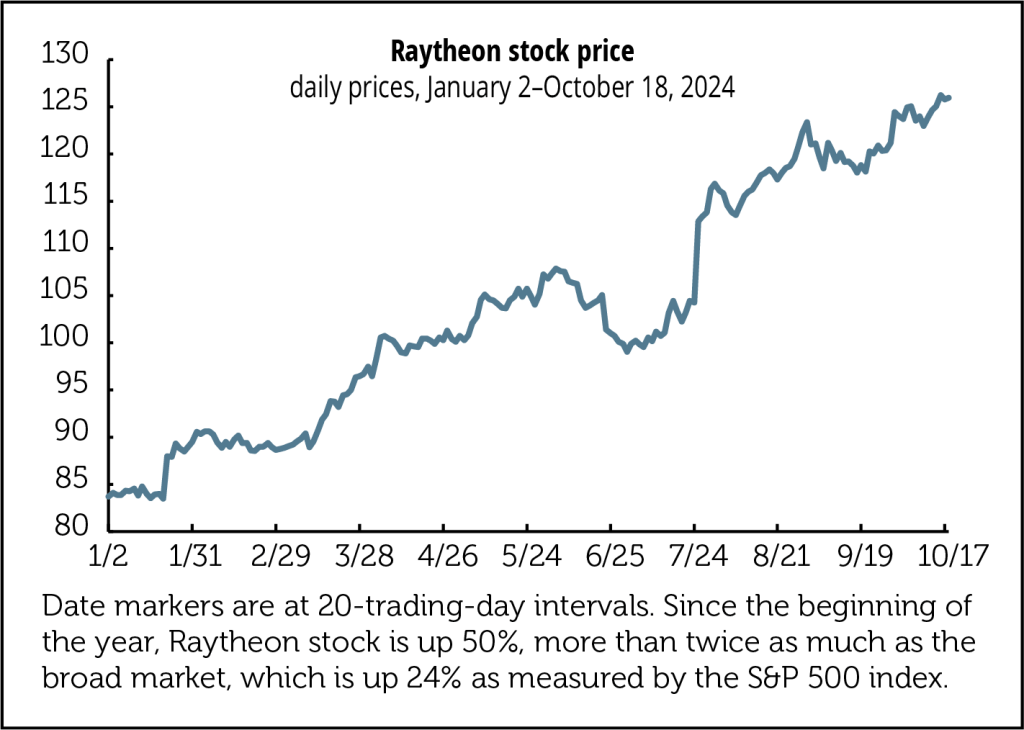

Well, it’s many elements. A very not historically unique but nonetheless unusual element is that provided by the Israel lobby because even if, well, as a previous generations of American diplomats pointed out, even if America is determined to exercise hegemony in the Middle East, blind allegiance to Israel is a crazy way of doing that. But beyond that, yes, the military industrial complex plays a role. You see Raytheon’s shares booming and Raytheon officials declaring hymns of joy over arms supplies to Ukraine and to Israel. But I think as well, every major country around the world with any kind of foreign security establishment has some form of foreign security doctrine, which everybody who wants to be part of that establishment has to sign up to. And if you dissent from it, you are kicked out. So you see that in China. The Chinese establishment believes that China has to return to its ancient role as a superpower, dominating its own region and with major influence, not exclusive influence, but major influence on world affairs as a whole.

If you don’t believe that, you’re not going to last long in the Chinese foreign security establishment. The Russian establishment believes in a multipolar world in which Moscow will be one of the poles. I mean only one. They know that America will always be a pole China will be a pole. India in future will be more and more of a pole, but Moscow must be a pole, *and Russia must be in a position to defend its vital interests on the territory of the former Soviet Union. Once again, if you dissent from that, you better start looking for another job outside the Russian establishment. And the American foreign security establishment has a doctrine. But the problem is that this doctrine is essentially a megalomaniac one. It is one greater than any country, even in a way the Roman and Chinese empires, which at least confine themselves while they had to their own regions and didn’t try to dominate the whole world. The British empire dominated large parts of the world, but from early on it knew that it couldn’t take on the United States, and it knew that it couldn’t actually unilaterally do anything on the continent of Europe.

It’s really only America that is believed that it both can and should dominate the whole of the world. But you have to believe that if you are going to get ahead, get to the top of the American system.

Okay, let’s do some detailed looks here. Ukraine first. In some circles, you can get in trouble for pointing to a US role in provoking the invasion of Ukraine, but you can’t really understand the whole crisis, much less think about solving it without conceding that. Is that possible?

I mean, it is possible because after all, you have a lot of highly intelligent American commentators and some Brits who have been saying just that Stephen Walt, John Mearsheimer, very distinguished retired American diplomats, Jack Matlock, Tom Pickering, the late George Kennan. So many people have said this, but ever since the expansion of NATO became a bipartisan matter in the mid 1990s, essentially anyone with a career to make has fallen into line behind this idea that NATO, under US domination, must be the only security institution on the European continent, with the right to dictate the terms of European security to everybody else. And that Russia has no security role beyond its own borders. And that as once again, people have been warning for 30 years now was bound to lead if not to actual war with Russia. Although the CIA warned of war with Russia in Ukraine in the mid-nineties, and of course the present director of the CIA, William Burns, warned in 2008 that NATO membership for Ukraine is the reddest of all Russian red lines and that the whole of the Russian establishment is violently opposed to it.

That is not an excuse for Putin’s invasion. And indeed, in private, a lot of Russians who regard themselves as Russian patriots and are now committed to at least avoiding defeat in Ukraine, in private and sometimes in public candidly admit that the invasion was a disaster from every point of view. But it was not—unlike what you read so many people saying—it was not the act of some crazed maniac. It stemmed from a view of Russian vital interests that is shared by the whole of the Russian establishment and that we set out to violate.

What is the US goal here, withdrawal of Russian troops, total collapse of Russia? Ukraine is looking weaker and weaker in the battlefield of making it harder to extract concessions from Putin at this point. So where is this all leading?

Part of the problem is that as indeed General Milley amongst others has hinted, and I think this is quite a general view in the Pentagon and possibly even in the CIA, we blew the chance for compromise with Russia on much better terms for Ukraine twice. The first was at the very start of the war when Russia and Ukraine were negotiating a compromise piece. This has been almost totally forgotten, but in the first month of the war, Zelensky in public said the following: Before the war, I went to every major NATO capital, including Washington. And I asked, can you guarantee that when within five years, Ukraine will be admitted into NATO? And they all said no. Zelensky then said publicly to the Ukrainian people, well, at that point we might as well have a treaty of neutrality with Russia with of course, international guarantees. And the territorial issues, on much better terms for Ukraine, would be shelved until future negotiation.

But of course, for whatever set of reason, but it does look as if the west played a major part, that process was abandoned. The second chance was in the autumn of 2022 when the Russians had suffered a series of really major defeats and might have been willing to accept a compromise. A compromise. I mean one that would not have involved Russian withdrawal from Crimea and the Eastern Donbas, but could have involved Russian withdrawal from other areas and a treaty of neutrality, but with really strong guarantees for Ukraine. But we didn’t take up that possibility. And now as you say, Russia is in a much stronger position. The Russians certainly feel that time is on their side. And if you look at European election results and opinion polls, it is extremely unlikely—well, German government has said this—that European aid can remain at anything like the present level for many years to come.

And if European aid diminishes, then two things will happen. Either a US president will have to go to the US Congress and ask for much, much more money indefinitely for Ukraine, or of course Ukraine will collapse. and we will have to seek a compromise peace with Russia up to now. I mean, you have leaks, you have suggestions in public, you have hints, but no western leader and precious few Establishment commentators have had the guts to come out and say, publicly, look, our previous demand for total Russian withdrawal from Ukraine is over. That’s not going to happen. The only chance to preserve most of Ukraine is to seek a compromise.

China, which is a growing adversary—though somewhat eclipsed by all the hot wars right now—what is the goal there? Some kind of containment to reverse China’s rise as a global competitor that seems doomed, which isn’t to say they wouldn’t pursue this strategy anyway, but what are they trying to accomplish with China?

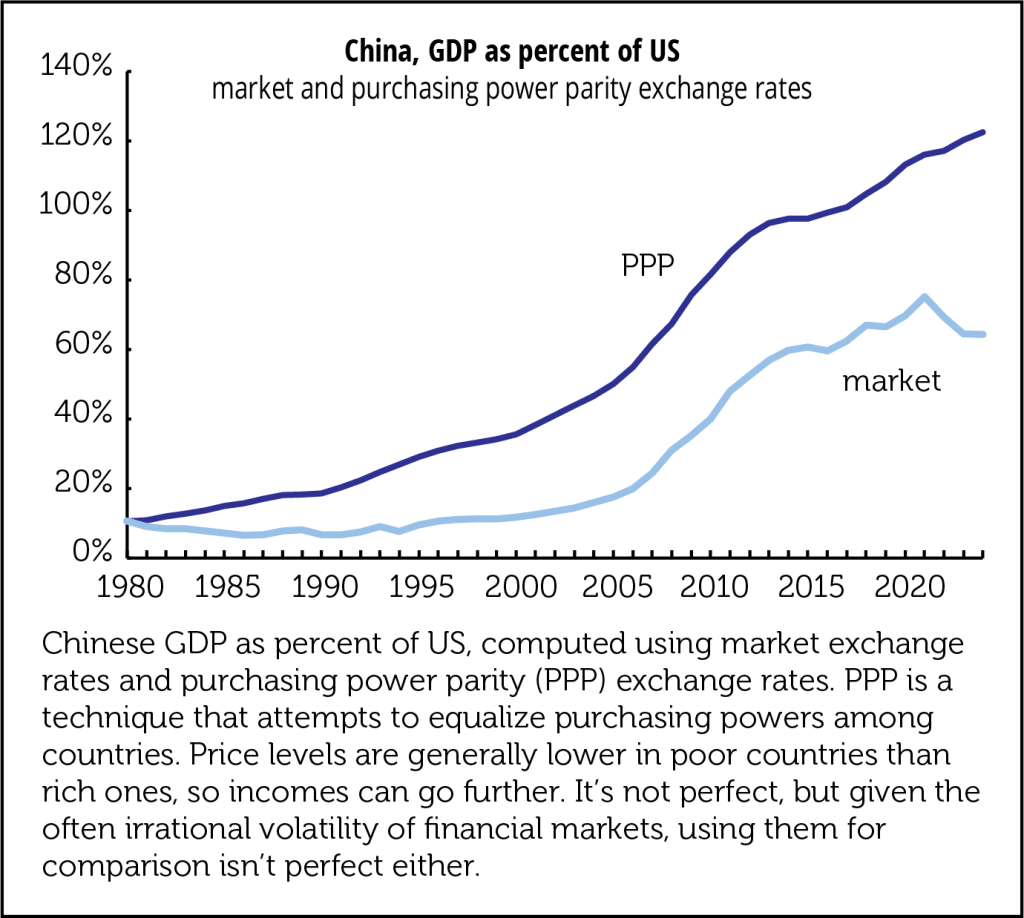

It seems that they are trying to contain China, both geopolitically and economically. I mean essentially to trap China at about its existing level of development, but without this leading to actual war and that, well, I don’t think that’s going to work because of course all development is not just absolute, it’s relative. And while China is obviously not growing nearly as fast as it did for most of the past 40 years, it’s still growing faster than the US and a lot faster than Europe, which means that the West as a whole is still relatively declining.

So, this makes the whole relationship with China totally different from the US rivalry with the Soviet Union, which obviously was in no sense an economically dynamic power as China is. And also of course, the wider world. The US could appeal to elites all over the world who were afraid often with good reason of Soviet communism, appeal to religious elites against Soviet communist atheism. It could even appeal to social Democrats who were afraid of Stalinism.

But of course, China doesn’t pose that threat at all. Despite all these attempts to talk about an axis of authoritarianism and China spreading its model, it isn’t. China has established a model, and people can follow it if they wish to do so, but there is no evidence of China trying through subversion or pressure to get Brazil to go back to dictatorship or Thailand to get rid of its monarchy. No, there’s none of that. And so of course most countries around the world do not want to choose between the US and China and react very badly to US attempts to force them to choose.

Well, if you’re talking about trying to contain China’s economic and political rise, if the name King Canute comes to mind.

Yeah, exactly.

Now Israel’s rampage. Mouin Rabbini said recently that people aren’t suffering from outrage fatigue over the warmongering because Israel keeps upping the ante of horrors. It does seem that way. And now at first US support seemed reflexive, almost atavistic. But as something else going on? I’ve been seeing such suggestions lately that Biden’s inner circle is actually enthusiastic about remaking the Middle East, which sounds suspiciously like what Bush and Cheney and the neocons were saying a couple of decades ago. How do you see this support? Is there just that atavism or is there some grander imperial design behind it?

In the wider US Establishment, it is a mixture of activism and let’s face it, fear, personal fear of the personal consequences. If you speak out against Israel within circles of the establishment, I mean this is open now on the part of the Neoconservatives and others, and of course the Neoconservatives have now moved back where they first came from 60 years ago into the Democratic party. You see this with Cheney supporting Biden. You see this with Kagan and Frum all the others now supporting Biden. Yes. I mean, I think that there is now a hope of, not in the same way because I don’t think anyone is talking about invading Iran, but basically doing to Iran, you know what the Bush administration did to Iraq, crippling it or even destroying it, breaking it up as a functioning state and thereby eliminating the last state in the Middle East, which is openly and determinedly hostile to both the US and Israel.

At that point, all you would have left is Syria under Russian protection, as long as the Russians hang on there. And then a collection of US client states, which will complain and make speeches in the UN like Jordan. The king of Jordan will bitterly denounce Israel in the UN while allowing US missiles to be based on his soil to shoot down missiles attacking Israel. And then from the Israeli and much of the US Establishment point of view, America and Israel would simply have won. They would then dominate the Middle East for all foreseeable time—except of course they wouldn’t, because as we found in 2011, the peoples of the Middle East also, well, they didn’t have a vote of course, but they have the ability to come out and overthrow their regimes.

The kind of hegemony of which the neocons and parts of the US Establishment in general are dreaming is, in my view, I mean simply politically unsustainable for very long. Leaving aside, of course, the question, which frankly is becoming simply a joke in the eyes of the vast majority of the world population, that US global hegemony was supposed to have a certain moral base, liberal internationalism and all that. Well, liberal internationalism is dead in the ruins of Gaza.

There’s this ridiculous charade of drawing red lines and then shrugging when they’re crossed. Now it’s over Israel’s apparent attempt to starve people out of Northern Gaza. But given the history that looks like another game of charades. Israel is also dismembering Lebanon. There seems to be no limit to us indulgence of Israel’s. Is there one?

When it comes to Israel’s treatment of its immediate neighbors? No. Clearly there isn’t. However, two questions. The first is just how far will Israel go, and would the US allow Israel to go in attacking Iran? As I’ve said, the neocons and parts of the Establishment would like Israel to go all in an attack on Iran, but despite recent Israeli successes, it’s questionable whether Israel can do that on its own or whether the US would have to come in as well. And then obviously you are talking about a much bigger conflict with, and, depending on how the Ukraine war goes and when it comes to an end, but you are most probably talking then about Russia and China really not in war, but in funding and weapons supplies coming to Iran’s help against the US as an obvious way of pushing back against us pressure on them in their own area.

So that’s the first question. Will the Israelis be confined to a limited strike on Iran, or will they go all in to try to destroy the Iranian economy, to destroy Iranian energy exports? And of course, if they do that, they could well produce a global economic crisis. Higher energy prices would have a terrible effect on Europe, but to some extent as well on the US public, which is one reason I think why nothing is likely to happen until after the US elections because the last thing that the Biden and Harris teams want is a surge in US gasoline prices.

That’d be curtains for them.

It would indeed. But what happens after the elections? We don’t know.

The second question, and this is something that we now have to look at very seriously, if you listen to or watch, not just the more extreme elements in the Israeli cabinet are saying, but large sections of Israeli society and Israeli academia—which are not being reported, of course by far, the greater majority of the Western mainstream media—are now talking about ethnic cleansing, driving the Palestinians from large parts of Gaza and replacing them with Israeli settlers and annexing this area and restricting the Palestinians more and more in the West Bank until large numbers of them leave. Or even the idea of simply deporting them all, driving them out into Jordan. You have this language in Israel about how Jordan is the homeland of the Palestinians and everything west of the Jordan is Israeli.

Would the US go along with that? The thing about that is that if the Israelis did that, it could or even probably would bring down the existing Jordanian state and monarchy. If they drove the population of Gaza into Egypt, would the Egyptian regime survive? Well, at that point, you are talking about key US allies in the Middle East being destroyed by Israeli actions. Would the US go along with that? I would’ve thought that at that point there really would be some kind of pushback in the US Establishment and the US military, but who knows?

Now to conclude this world tour, Biden is on the way out. So let’s talk about the successors. What does Harris’s foreign policy view look like? Does she have one other than more of the same? The way she’s been recruiting neocons to her campaign, it looks like it’s not just electoral arithmetic trying to get all those Republican voters, but it does seem to reflect some of her thinking. What do you make of it?

Yes. It will be either more of the same or it will be worse. We have to see who makes up Harris’s team. We just don’t know. People talk about Phil Gordon, and he is certainly a moderate and has very close European contacts and affinities. But as with Obama, you could find a Secretary of State like Liz Cheney, God forbid, who would simply ignore the wishes of other members of the Cabinet and drive a neocon agenda. And since Harris clearly is absolutely ignorant of international affairs, hopelessly so, one can well imagine that a determined enough team of neocons could make us policy much worse. I certainly don’t think there’s any chance of it being much better.

Trump. It’s impossible to predict anything about that guy. He’s so impulsive and shallow, but there are some people who view him as a peace candidate of sorts. Is there any truth to that?

Trump does appear to have understood that the American people do not want more wars with American troops actually being involved and killed on the ground. And of course, his Vice President Vance did lead the charge in Congress against unlimited and indefinite funding for Ukraine. And on Ukraine, Trump has said that he will seek a peace settlement and given that so much of what’s happening on the ground is heading in that direction anyway, I think there is some chance of that. But in the Middle East, he is just as absolutely pro-Israel as the Biden administration and could be even more unhinged when it comes to an attack on Iran. The only hopeful thing is that in the past we’ve seen again and again, for example, with regard to North Korea, that Trump will make these ferocious trumpeting statements and then not actually do anything about it.

And then there’s China. The only thing to be said for the Biden administration is that it does seem to have been aware most of the time, not always, of the extreme delicacy of this situation. So, when Pelosi insisted on going to Taiwan, this was not something that Biden wanted. Well, delicacy and Trump are not words that go very well together, but once again, it’ll depend on who he chooses as his Secretary of State. It will depend on how much influence Vance has within the administration. It will depend on all these things that we just don’t know.

I have to say, it’s a damned odd picture for democracy. You have a series of issues which are involving the US public in enormous costs, hugely high spending coming out ultimately of taxes. You’ve got issues which in the worst case scenario could actually lead to the nuclear annihilation of the United States or the least of crisis that would bring the entire world economy and the US economy down in ruins. And the US public have not actually been told what either of these candidates would do. This isn’t a pretty picture as far as democracy is concerned.

Is all this, not to mention the general devolution of our political class, what it’s like to live in a declining empire, one unable to face its own decline graciously. The level of chaos and violence seems like a product of decay.

When I was born, Eisenhower was still just president of the United States, and Ike, with all his faults, was a great man, very thoughtful leader. And now we have Trump and Harris. But of course, this is 64 years on. And I mean, when you think about it, 64 years is longer than the time that separated Bismarck from Hitler or Marcus Aurelius from one of the more decadent and loathsome Roman third century emperors. A lot can happen in three generations, and a lot of decadence and decline can happen during that time.

Fresh audio product: the Biden/Harris grand design, the emptying Balkans

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

October 17, 2024 Anatol Lieven on the ambitiously aggressive grand design of the Biden/Harris foreign policy • Lily Lynch, author of this article, on the emptying out of the Balkans

Fresh audio product: new Marx translation, Israel after October 7

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

October 10, 2024 Paul North and Paul Reitter on their new translation of Marx’s Capital • Nimrod Flaschenberg and Alma Itzhaky, authors of this article, on the political culture of Israel after October 7

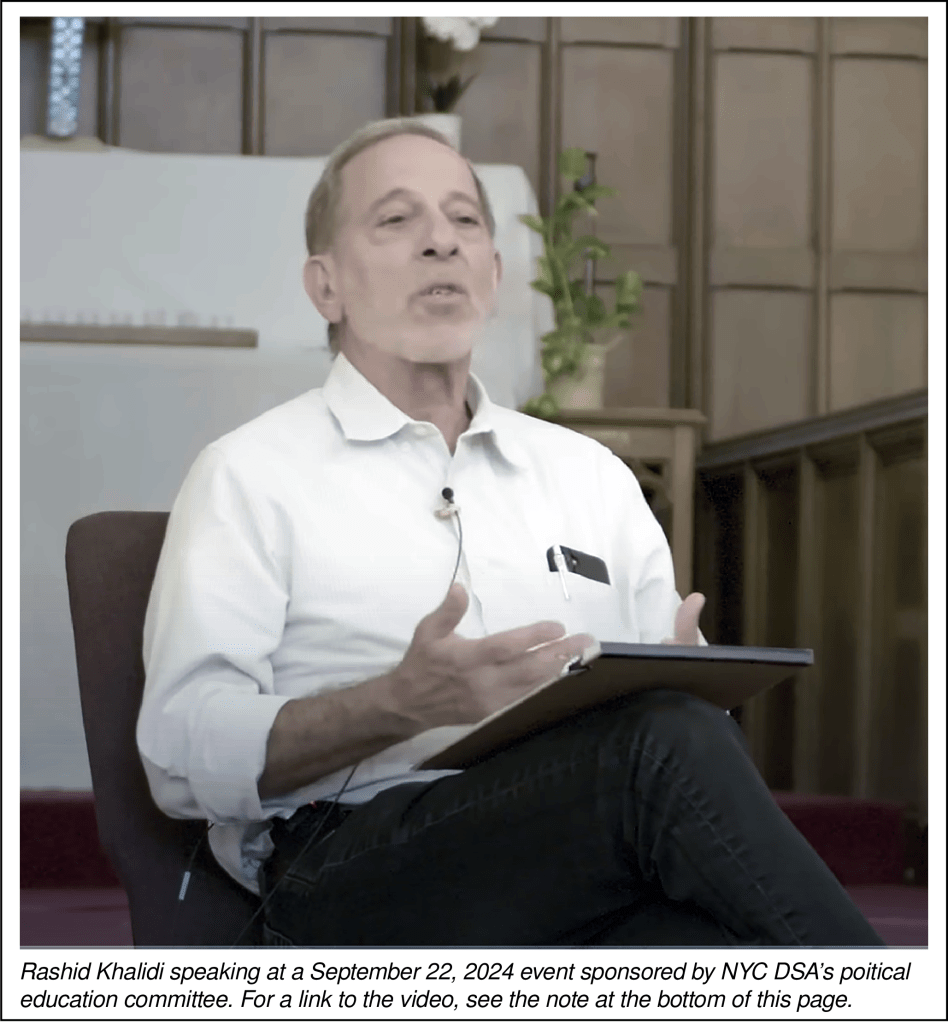

Rashid Khalidi on settler-colonial Israel: an interview

This interview with Rashid Khalidi, author of The Hundred Years War On Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, was broadcast on Doug Henwood’s Behind the News, October 3, 2024. Khalidi’s family was a member of the old Palestinian elite that was destroyed in 1948 when Israel, freshly born as a state, expelled three-quarters of a million Palestinians from their homes to make way for the settlers. Along with the larger history, he writes extensively about that family in the book. It’s not a new book—though BtN has never been impressed with novelty for novelty’s sake—but it has acquired a new relevance given the latest phase of that century-long war. Khalidi has been an academic for much of his life, but he’s also been deeply involved in Palestinian politics over the years. He’s just retired from teaching at Columbia University, where he now has emeritus status. It’s been lightly edited for publication.

Applying the term “settler colonial” to Israel really annoys its supporters. But not only is it accurate, it’s the language the early Zionists used. Could you review the history of that discourse?

The early Zionist leadership, people like Theodor Herzl, Chaim Weizmann, Ze’ev Jabotinsky, David Ben-Gurion, all believed they had a right to take over Palestine. They believed they had a Biblical right, they believed had a right as people persecuted in Europe in need of a refuge. They represented a national movement, an attempt to develop a national movement out of Judaism and the Jewish people, a modern national movement. At the same time, none of them made any bones about the fact that they were doing this as part of a settler colonial process. The names of the institutions, like the Jewish Colonization Agency, one of the major institutions that was involved in taking over land from Palestinians, indicates that they understood that this was a process of colonization.

The one who was the most open about it was Jabotinsky who said that this is a colonial process: we have a right here, but we understand that this is like any other colonial process and colonized peoples always will resist. Others were less forthright about it, but they all understood the same thing, that whatever their rights were, whatever the justice of their cause in their eyes was, they were doing something that involved displacing an entire people in a colonial process. Nobody ever contested that really before World War II, when suddenly decolonization began, and colonialism had a bad odor globally. And so the Zionist movement and then later Israel began to describe itself as an anticolonial actor because they had come into conflict with the British for a number of years during anf immediately after World War II. But the colonial settler nature of this was confirmed after Israel’s victory in 1947, ’48, ’49, when they expelled three-quarters of a million Palestinians stole their land, refused to allow them to return, took over all of their property. This is settler colonialism. There’s no other description for it really. And anybody with eyes to see who has watched the process of the colonization of the West Bank, the Occupied Territories, Jerusalem, and the occupied Golan Heights since 1967 cannot see anything but settler colonialism. I mean, I cannot imagine how you would describe it unless you’re a Biblical fanatic and say, this is the return of the Jewish people to land to which only they have rights. Well, if you believe that we are not involved in the same discourse.

A striking thing, reading the history is how the Zionist project has relied on imperial patrons—which counters all the David and Goliath metaphors,—the settlers just to sell their project. First it was Britain. Now the US. Sometimes one wonders what was in it for the patrons. So let’s talk a bit about the British—why their fervor from Balfour onwards? The British ruling class is a long history of antisemitism. Did they just want to get the Jews out of Europe? What explains the fervor for the project?

Two things explain the fervor for the project. The first is ideological. It goes back to the early 19th century before modern political science had ever developed, before even the first modern political Zionist writings were committed to paper. And this has to do with a movement in the Anglican Church in England, and among Protestants generally, a great renewal of faith and a rereading of the Bible such that the return of the Jews to the Holy Land was seen as a bounden Christian duty in order to hasten the Second Coming of Christ and so forth. We get the same view among many Evangelicals in the United States today. This starts in the early 19th century, both in the United States and in Britain. The figure most closely associated with it is a very influential British aristocrat by the name of Lord Shaftesbury. He was the father-in-law of the British Prime Minister Lord Palmerston.

He and many others pushed this and this became ingrained in the British Protestantism, this understanding that it was a bounden duty to return the Jews to the holy land. Now, it just happens that at the same time, you have, as you pointed out, a deep strain of antisemitism in England, which goes back to the 12th century when King Edward kicked all the Jews out of England. It was one of many cases where European rulers expelled the entire Jewish population. The King of France did it in the 13th century. The kings of Spain and Portugal did it at the end of the 15th century. And that virulent, theologically based antisemitism was there at the same time as you had this, I guess you’d call it philosemitism or Christian Zionism, among members of the British ruling class. The great irony is that Lord Balfour, who obviously is the person who pens the Balfour Declaration on behalf of the British cabinet in November 1917 in a previous incarnation as conservative Prime Minister, was responsible for one of the most antisemitic acts since King Edward, which was the Alien Exclusion Act to prevent Jewish refugees from the pogroms, the deadly pogroms that were going on in the Russian Empire at the turn of the 20th century, from coming to Britain.

So, you have both of those elements which have to do with philosemitism and Christian Zionism and antisemitism. And secondly, and I think much more important, you have a strategic element. Britain realized early on in the 20th century that it was absolutely vital to its strategic interests, control of the shortest route to India, which meant control of the Suez Canal in Egypt, which meant protecting the eastern frontier of Egypt, which they saw as vulnerable, and which in fact turned out during World War I to be vulnerable, by controlling Palestine and the related realization that there was a possibility of the building of a railway between the Mediterranean and the Gulf, which would become the shortest land route through the Mediterranean, then via railway to the Gulf. And the British decided they had to control that as well. That’s why you have some very peculiar shapes on the map today.

That eastern arm of Jordan, which connects with the western edge of Iraq, is a British concoction to ensure British control of that shortest land route between the Gulf and the Mediterranean. And Palestine is the Mediterranean terminus of that. So for multiple strategic reasons, the British had decided long before Chaim Weizmann, came along, long before Balfour was foreign secretary, that they needed to control Palestine. This was a decision of the Committee of Imperial Defense, of the British General Staff, of British ministers in 1906, ’7, ’8, ’9, ’10, ’11, ’12, long before the Balfour Declaration. So strategic reasons and the idea that the Zionist movement would be a useful pawn in this that enabled Britain after World War I to ignore their promises to other countries to have an international regime in Palestine and to take Palestine for themselves. So, there are strategic reasons and the ideological reasons that I mentioned.

Over time, the Zionists proved very skilled at playing their imperial masters to their advantage.

One of the things you have to understand if you accept that this is a settler colonial project, is that it’s unique. It’s different than any other. Most of the others are extension of the sovereignty in the population of the mother country. Zionism didn’t have a mother country, but it needed an external metropole. And so Herzl ran around Europe to the Kaiser, to the French, to the Ottoman Sultan, to try and find that external patron. Weitzman hit pay dirt in London with the British government. That was something they always understood. That is absolutely vital to keep these external patron or patrons because the project necessitates that anchor in Europe and later on in the United States. That’s something that they used to their advantage when the British decided to limit their promises to the Zionists in 1939, and they pivoted very quickly to the United States and the Soviet Union who became their patrons in the immediate postwar period, pushing through the Partition resolution, which is the birth certificate of the state of Israel, the 1947 General Assembly resolution, partitioning Palestine, both recognizing the state of Israel immediately—it’s established in May 1948—and providing Israel with the arms, which enable it to defeat the four Arab armies that it fought against in the 1948 war.

This attentiveness to external patrons. They later on shift to Britain and France who supply most of their weapons in the fifties and sixties. The weapons that they win the 1956 war and the 1967 war are mainly French and British weapons, and it’s the French who gave them the wherewithal to develop their nuclear weapons. Later on, they pivot to the Americans. So, there’s always been a concern to maintain an anchor in a western European/American metropole for this project, even as it became based in Israel after the establishment of the state.

I don’t want to emphasize the flaws and weaknesses of the Palestinian side too much given the overwhelming power and brutality of Israel and its patrons. But there are some issues to talk about here. One, you write a lot about your family in your book, which was part of a Palestinian elite. You’re critical of that elite. It didn’t seem up to the task, to use the Marxist language, of forming a national bourgeoisie. What were its limitations?

Well, the first thing is it was largely not a bourgeois leadership. The first thing is that it was largely a leadership rooted in the traditional notable class, which were people who were landowners, which were people who were part of the bureaucratic elite of the Ottoman Empire, and who hoped to continue that role under the British and their brethren and sistern, or mainly brethren, in other Arab countries did that. They were not a bourgeoisie. The bourgeoisie was a junior partner in that leadership of the 1920s and 1930s. They were not particularly democratic. They were not engaged in mass politics for the most part. They were traditional leadership of what Albert Hourani called notables, the kind of people who had been part of Ottoman governance for generations and generations, centuries actually. And they hoped and assumed that they could continue to play that role under the British

They were sorely mistaken because they fundamentally misunderstood what the British were doing. The British intended to replace them and their people with an entirely different leadership and an entirely different people. That’s what the Balfour Declaration said. That’s what the mandate for Palestine said. And one of the great failures of this leadership was to realize this early enough. Eventually, Palestinians realized this and rose up in revolt, but it wasn’t a revolt that was organized by or led by this traditional leadership. It was a grassroots, popular uprising that led to a three year rebellion that the British only put down with great difficulty. And the leadership doesn’t come off well in my reading and in the reading of most historians during this period from World War I to 1948.

And you also write about how over the decades the leadership of the PLO has been ill-prepared, no match for the Israeli counterparts, no political strategy to influence outside opinion. The leadership enjoyed its perks and forgot their constituents. Now, we shouldn’t overlook how many of the most dynamic leaders Israel assassinated—even in the cultural sphere—but the leadership has been fairly unimpressive. Why?

A couple of things. I’m very critical of them. But they achieved certain things. You have to give them credit for resuscitating the Palestinian national movement in the fifties and sixties at a time when everybody thought that Palestine had disappeared from the map. The Israelis were gloating. I believe it was Golda Meir who said, the old will die and the young will forget. Well, the old died, but the young did not forget, and it was this leadership that revived the Palestinian national movement, to their credit. It had been completely destroyed, shattered. The previous leadership was discredited. They were all scattered to the winds. That class and those individuals and those families that had dominated Palestinian politics up to 1948 disappeared from the political map. And the new ones, to their credit, resuscitate the Palestinian national movement and get the Palestinians a seat at the table.

Now, what they did with that seat is where the burden of my criticism comes in, which is that they utterly failed to understand the global balance of power, to understand the United States and Western Europe, to understand how those places functioned and how hard it would be to overcome the visceral nature of Western support for the Zionist project and for Israel. I think a comparison with the Zionist movement and Israeli leaders is quite useful here. You’re talking in the case of people like Herzl, Ben-Gurion, Weitzman, people like later on, Abba Eban, Golda Meir, Benjamin Netanyahu, of people who are Americans, Europeans in their origins, in their education, in their outlook, in their training, in their language, and their culture, and are also Israelis, or Zionists for the ones who like Herzl who die long before the state is created Jabotinsky. All of these are people who are at home in the European milieu.

They understand Europe and the United States. Golda Meir lived in Milwaukee for years. Netanyahu lived in Philadelphia and at Cornell where his dad was teaching for years. You listen to them, you listen to Golda Meir, you listen to Benjamin Netanyahu, and you hearing the accents of natives from this country. And that’s true of Abba Eban and speaking perfect Oxford English. He was South African by origin. So, you’re talking about an elite in the Zionist movement and later in Israel, a large proportion of whom profoundly understand Western culture and politics because they were part of it. That’s not the case for the Palestinians. Until the present generation you do not have people who’ve grown up and have been steeped in Western politics, Western culture, Western languages, Western law, and they therefore were in an enormous disadvantage by comparison with Zionists and later Israeli leaders in dealing with the West, whether strategically or in terms of public relations or diplomatically or in any other way. And that has shown unfortunately in the performance of the PLO, well, the Palestinian leadership of the twenties and the thirties, but the performance of the PLO and more recently of the Palestinian Authority. They’re pathetically out of their depth in dealing with the United States and Western countries. The PLO did a pretty good job dealing with the Third World. They were relatively successful. They could understand that Global South because they were part of it. They could relate to it, they could speak to it. They did not have the same facility with the United States and Western Europe.

I can understand the Cold War logic of an alliance with Israel as a bulwark against Communism. The USSR has been dead for over 30 years. Most Arab regimes are now very reliable US allies. So how do you explain the lingering support for Israel and its absolutely manic intensity?

Well, there’s multiple elements. I mean, you have the Evangelical element, which is a throughline from Britain in the 1930s and 1940s through the United States in the 2020s. That is a base of support that is solid in every era, given that it’s theologically grounded. Second thing that you have that’s important is that all of the leading institutions of the Jewish community have been won over to Zionism between the 1940s and the 1960s. Most Jewish communities in most parts of the world were not particularly favorable to Zionism until Hitler comes to power in the thirties and until the Holocaust. That’s true in the United States. It’s true in Europe. People voted with their feet. Thousands went to Palestine, [laughs] millions went to the United States and Canada and Australia. Or they stayed and tried to change their societies or keep their heads down. They were not convinced of the tenets of Zionism until European antisemitism reached this mad paroxysm of the Holocaust.

And that understandably changed a lot of people’s minds. And by the 1960s, the American Jewish Establishment, the leading institutions of the American Jewish community, had come to treat Israel as a central element in Jewish identity as they came to treat the Holocaust as a central element of self-understanding. And the two were seen as linked, of course. So that’s another element. It’s increasingly unrepresentive of younger generations of people in the Jewish community, but it’s certainly true of the people in the sixties and seventies who own most of the money and controlled most of the institutions. The Conference of Presidents and the ADL and the American Jewish Committee and so forth are run by people whose political consciousness was formed in the fifties, sixties, and seventies. And that was an era in which an Israeli narrative took root in that community.

And then finally, you have strategic elements. You’re absolutely right that Israel was a particularly valuable ally during the Cold War. It was seen as the trump proxy against Soviet proxies. But you’re also right that the Cold War ended in 1991 with the demise of the Soviet Union and that the United States has continued to see Israel as a valuable ally because the United States has found other bogeymen to justify its strategic stranglehold over the Middle East—the Islamic Revolution in Iran and the regime that grew out of that, and then later on, various terrorist outfits like al-Qaeda and ISIS. And Israel successfully sold itself at the turn of the 21st century to the United States as an indispensable ally in the global war on terror. And we see this today in the seamless cooperation between the American intelligence services and the American military with Israel in hunting down Hamas leaders in Gaza and in hunting down Hezbollah leaders in Lebanon.

There’s reportage in the New York Times, which is the main propaganda outlet for Israel in the United States, this is taking place, and this goes back to this idea that these things are joined at the hip. Everything that the United States finds objectionable in the Middle East, including global terrorist outfits like al-Qaeda and ISIS are no different than Hamas and Hezbollah, which of course have national roots and national causes, and are rooted in the Palestine issue and in Israel’s occupation of Lebanon, and not in some global Islamism. But there’s a narrative that Israel succeeded in selling in this country—Netanyahu played a crucial role in this, but it was Ariel Sharon who was really the most successful salesman at the outset—such that the United States has hitched itself essentially to Israel’s war on a variety of actors in the Middle East, with the complete illusion that these are America’s enemies just as their Israel’s enemies. It’s hard to see exactly how Hamas is the United States’s enemy, except that it’s linked to Iran and this hostility between the United States and Iran. this enmity, goes back to the Iranian revolution.

You wrote in The Hundred Years War, which was published in 2020, so I guess you wrote these words in 2018 or ‘19, about how American public opinion was changing, and we’ve certainly seen that accelerate over the last year. How wobbly is the Zionist discursive hegemony these days in the US?

Well, it depends on who you talk about. If you talk about public opinion in general, that hegemony has disappeared. It’s fighting a rearguard action, and because its narrative is so threadbare, it’s obliged to resort to completely spurious allegations of antisemitism to smear people who are calling for Palestinian freedom or people who are decrying the slaughter of civilians in Gaza now in Lebanon. On that level, it’s fighting a rearguard action. On the elite level, however, on the level of the mainstream corporate media, on the level of the great institutions of our society, the universities, the museums, the foundations, on the level of our politics, it’s still hegemonic. There’s not a politician who doesn’t repeat some drivel that’s drawn from this Israeli playbook every time they open their mouth. “The only democracy in the Middle East”—a country that’s kept a population almost as large as the Jewish population of Israel under prison camp conditions and military occupation since 1957 is the “only democracy in the Middle East”?

Millions of Palestinians have lived under the jackboot of a military government locked up in Gaza or held in cantonments all over the West Bank by Israeli walls and Israeli checkpoints without any right to determine anything about their lives, whether they can go, they can come, they can import, they can export, that they can’t register their children in the without Israeli permission. That’s a democracy? There isn’t a politician who doesn’t repeat that nauseating lie. Roger Cohen, today’s New York Times, shared democratic values. So let me see. Torture in prison camps is a democratic value. Slaughtering civilians at a ratio of three to one or four to one, as against your nominal enemies, is it in a democratic value? That bilge is repeated ad nauseum by all of the elites, whether the political or the media or the corporate or the other elites. So, on one level, that narrative is still hegemonic, and that’s unfortunately the level of the people who own and control our politics and our economy and much of our cultural production. At a grassroots level among artists, among students, among unions, among churches, and among minorities, that narrative is in deep, deep trouble.

Is there a way out of where we are, one secular democratic state sounds appealing but impossible to imagine. The old two state solution with the Palestinian one fully sovereign and not an apartheid style bantustan—that seems almost as dreamy, more dreamy than ever after this latest round of bloodletting. And given the destruction of the civilizational infrastructure, the Palestinians, and the hardening of Israeli attitudes, can you imagine any kind of plausible solution at this point?

Well, I don’t think anything is possible in the immediate future, given what you just said. Israel suffered a series of traumatic shocks on October 7th. It was the first invasion of Israeli territory since 1948. It was the largest civilian death toll in Israel since 1948. It was the most severe defeat of Israel’s military, certainly since 1973, and 800 civilians were slaughtered. It was a massive intelligence failure. The traumatic shock of all of that is still reverberating in Israel and has very much hardened Israeli attitudes. The slaughter of 42,000 people in Gaza, as you can imagine, has hardened Palestinian attitudes and the ongoing slaughter of, whatever the toll is, 1,200 people, most of whom as always with the Israelis are civilians, is going to harden attitudes in Lebanon and other parts of the Middle East.

So, nothing can be envisaged in the short term. In the medium and long term, you’re going to see decreasing support for Israel in the West. This ludicrous idea of shared values is going to be tattered. Now, Western values may change. The West may become more autocratic, more undemocratic, more hostile to the rest of the world. That’s certainly possible. The rhetoric of a Trump or the rhetoric of an Orban or the rhetoric of the Austrian party that just won the election indicates that that’s a possibility. In which case, Israel is a perfect ally. Tramples all over international humanitarian law, spits at the United Nations, is hostile and racist towards non-Jews. That’s an attitude that I think a lot of major political parties, including the Republican Party, would find perfectly congenial. But unless that is the future of Western European countries and the United States, there’s going to be a separation of ways between this absolutely essential metropole and this project in Israel.

And there’s going to be a problem within Israel because a lot of people are going to say, is this the country I want to bring my children up to live in? There’s a flight of people from the Middle East. There’s a flight of Israelis from Israel. There’s a flight of Palestinians and Lebanese as well. A hundred thousand Lebanese left for Syria in the last 24, 48 hours. Imagine going to Syria, a war-torn country because you’re in such danger in Lebanon. But Lebanon, Palestine, Jordan, Egypt, Syria, those countries are going to endure. Israel is going to have a problem because the kind of people who are leaving are the doctors from the hospitals, the high-tech folks, the investors, the professors, the more liberal element of Israeli society, and also the more educated and more productive members of Israeli society. And this is going to be a problem going forward. Do you really want your children to be occupying South Lebanon in 2030? Do you really want your children to be occupying Gaza in 2028? Well, that’s the future that this regime, this government in Israel is plotting for that country. I don’t think that that’s a future a number of Israelis at least, are going to enjoy living with.

Video of Rashid Khalidi’s conversation with Carrington Morris, a September 22 event organized by New York City DSA’s political education committee, is available here.

fresh audio product: a century of war on Palestinians, Hezbollah after Nasrallah

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

October 3, 2024 Rashid Khalidi, author of The Hundred Years War on Palestine, talks about Israeli settler-colonialism and its imperial patrons • Aurélie Daher looks at Hezbollah and the challenges it faces after the assassination of its leader

Fresh audio product: wildfires in Brazil, transition in Mexico

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

September 26, 2024 Forrest Hylton, author of this article, on wildfires in Brazil and the political impotence of Lula’s administration • Edwin Ackerman on politics in Mexico as AMLO hands over power to Claudia Sheinbaum, having engineered a controversial overhaul of the judiciary (article here)

Fresh audio product: boys talk, economists on inequality

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

September 19, 2024 Niobe Way, author of Rebels with a Cause, on the emotional and social lives of boys and what they’re telling us about society • Branko Milanovic, author of Visions of Inequality, reviews what economists have said about the topic over the centuries

Fresh audio product: durability of slaveholder wealth, a conservative looks at the election, effects of teachers’ strikes

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

September 12, 2024 Neil Sehgal, co-author of this paper, on the durability of slaveholder wealth, via a look at Congress • Emily Jashinsky with a conservative’s view of the election • Melissa Lyon, co-author of this paper, on the effects of teachers’ strikes

fresh audio product: German neo-Nazis, the superrich

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

September 5, 2024 Robert Pausch of Die Zeit on the far right’s strong showing in German regional elections • Rob Larson, author of Mastering the Universe, looks at the superrich

Fresh audio product: upsurge in Bangladesh, writing the Indian constitution

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

August 29, 2024 Naomi Hossain explains the uprising in Bangladesh that deposed PM Shekih Hasina • Sandipto Dasgupta, author of Legalizing the Revolution, examines the transformation of India from colony to nation through the exercise of constitution-writing

Fresh audio product: better approach to China, reviewing Petro in Colombia

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

August 22, 2024 Jake Werner on a progressive China policy (paper here) • Gabriel Hetland, author of this article, on the record of Colombian president Gustavo Petro, a leftist trying to govern a deeply conservative country

Fresh audio product: a look at Jeff Yass, another look at the “pro-worker” GOP

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

August 8, 2024 Arielle Klagsbrun of the All Eyes on Yass Campaign on the insufficiently known right-wing funder Jeff Yass • Sohrab Ahmari and Hamilton Nolan debate the existence, real or imagined, of pro-worker Republicans