Does productivity = unemployment?

There’s a controversy aflame in the left–liberal blogosphere around a revelation in Ron Suskind’s new (and apparently error-riddled) book, Confidence Men. (Brad DeLong has the page.) Suskind reports on tense high-level meetings within the Obama administration as it became clear that the StimPak wasn’t really working. Unemployment was drifting higher, and the Keynesian faction—Christina Romer, then chair of the Council of Economic Advisors, and later Lawrence Summers, then resident wise man—was calling for more stimulus. Obama said no. It was politically impossible, but Obama also argued that the productivity revolution has made workers obsolete. Against that, a few hundred bill in further stimulus—which would be DOA in Congress in any case—would do little.

Romer and Summers (who, it hurts to say, has been looking pretty good recently) argued that productivity need not create unemployment. After Obama supported an orthodox briefing by former OMB head (and inexplicable sexpot to some) Peter Orzag (who also recently said that we need less democracy to have a sensible fiscal policy), Romer objected, urging a more expansive fiscal policy. Obama cut her down in what Suskind calls “an uncharacteristic tirade.” A few months later, with unemployment now over 10%, Summers essentially made Romer’s earlier argument, and Obama listened “respectfully.” After the meeting, Romer said to Summers, “Larry, I don’t think I’ve ever liked you so much.” He told her that the feeling would pass—but then noted that Obama had been a lot more “generous” with him than her. When you’re on the wrong side of Larry Summers on feminist issues, you’ve got a serious problem.

Matt Yglesias assures us that his conversations with administration officials report that Summers and Romer won the productivity=unemployment argument eventually, and convinced him that the problem was low demand, not high productivity. But Yglesias himself also reports on an interview that Obama gave in June in which he blamed ATMs for high unemployment. And airport self-check-ins too. Stuff like that, that any globetrotter sees. So apparently Obama still believes that there’s only so much gov can do because all these business geniuses are using machines so cleverly.

Respectable Keynesians argue that the problem is demand, which is a cyclical argument more or less, while the productivity story is more structural. But maybe both sides are right in a way. Productivity is way up but wages are flat. Workers have seen little of the productivity revolution.

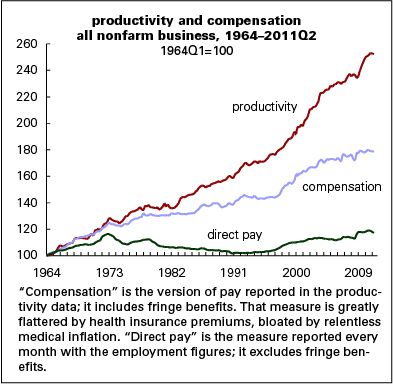

The canonical tech-driven productivity acceleration took hold around 1995. From then until the cyclical peak year of 2007, productivity growth averaged 2.6% a year—4.3% in manufacturing. Compensation, which includes fringe benefits (see graphic caption), rose 1.7% a year—and 1.5% in manufacturing. Direct pay overall rose 0.9% a year—0.3% for factory toilers. During the recession, productivity growth slowed, employment collapsed, and wages rose modestly. In the “recovery years” of 2010 and 2011, productivity growth—this time not from a tech revolution but from sweating a shrunken workforce harder—has resumed growing at a 2.6% pace (2.1% is the very long-term average, by the way). But both compensation and direct pay have fallen by an average of 0.3% a year.

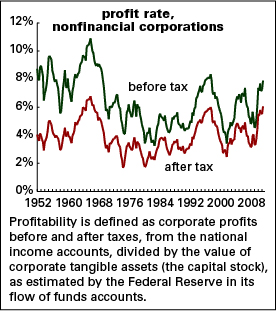

If workers were paid better, there wouldn’t be so much of a demand problem, would there? But then we stumble upon a contradiction: the entire recovery in corporate profitability that began in 1982 came from squeezing wages and workers. The trajectory of profit expansion is very uplifting—returns are roughly double what they were in the early 1980s:

After the profitability collapse of the 1970s, things began to turn around as the Volcker recession and the PATCO firing transformed capital–labor relations. Corporations enjoyed dramatically improving returns from the early 1980s through the late 1990s. Profitability took a major hit in the early 2000s recession, with the bursting of the tech bubble, but it recovered, only to stumble again in the 2007–2009 recession. But it’s staged a remarkable recovery. In the second quarter, nonfinancial firms were more profitable than they were at any time since 1997, in the frenzy of the dot.com moment.

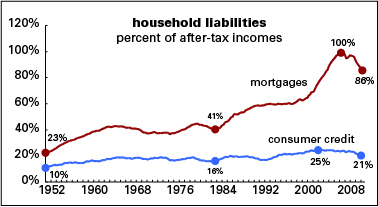

For most of the last 30 years, much of the working class was able to borrow what it wasn’t earning to make ends meet. Household debt rose strongly:

Mortgage debt rose from 41% of after-tax income in 1983 to 100% at the 2007 peak. It’s since come down hard, and the economy and political mood show it. Consumer credit—auto loans and credit cards and such—went from 16% to 25%. It’s come down too.

So here’s the demand problem: there’s no longer an endless supply of easy credit to make up what’s not in the paycheck. The greatest product of the productivity revolution is the production of profits, which has enabled a vast upward distribution of income and wealth. No one really wants to touch that one. So what’s a capitalist order under no serious political challenge to do except dither and squabble?

This post seems like a good place to note this work on how greater income inequality can lead to greater private indebtedness, as it echoes what you’ve been saying.

Excellent, excellent post.

BBC blogger Adam Curtis recently brought up the trap of TINA and von Hayek here:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/adamcurtis/2011/09/the_curse_of_tina.html

Pretty much it echoes his earlier film “The Trap”….what we are seeing here is an orthodoxy that will not die, a zombie economics. Somebody needs to put it out of its misery, but it won’t be the sitting government.

Doug:

Thanks for this and your other recent post. As always, a lot to ponder. I hope to see like this in the future.

well, they are likely to do what they always do and help to restore profitability through driving wages and social security down even further in the name of austerity and balancing the budget

Interesting stuff.

“The canonical tech-driven productivity acceleration took hold around 1995. From then until the cyclical peak year of 2007, productivity growth averaged 2.6% a year—4.3% in manufacturing. Compensation, which includes fringe benefits (see graphic caption), rose 1.7% a year—and 1.5% in manufacturing.”

Obama made this exact point in a campaign interview with David Leonhardt for BusinessWeek magazine. He said worker compensation had not kept up with productivity increases through the Clinton and Bush years and that it wasn’t fair. I thought he’d be better on economics b/c of that on other things he said.

Supposedly in the Suskind book Romer is quoted as saying that Obama came up to her and said “so the Fed has blown its wad?” So he does (did?) agree with Doug on monetary policy just “pushing on a string?” Maybe it explains why he didn’t make nominations to the Federal Reserve a priority and why there are still vacancies.

Regarding Yglesias, it usually boils down to Republicans bad and Democrats good, so I would guess he doesn’t want to credit Bush with a housing “boom.”

The Bush tax cuts could have added to the bubbliciousness of the last decade. And then there’s the Global Savings Glut and the Chinese not wanting to ever have to go to the IMF for help.

Even if it’s true, this just sounds like a good reason for work sharing. The point of technology once upon a time was to open up more leisure and for robots to do all the unpleasant work for us. Obama is just a lazy thinker.

Obama discussed these issues during his campaign for the Presidency.

from a Wall Street Journal interview (no link)

“We have drastically increased productivity since 1995, and there was the theory that if you increase productivity enough some of these problems of living standards would solve themselves. But what we’ve seen is rising productivity, rising corporate profits but flat-lining or even declining wages and incomes for the average family.

What that says is that it’s going to be important for us to pay attention to not only growing the pie, which is always critical, but also some attention to how it is sliced. I do not believe that those two things — fair distribution and robust economic growth — are mutually exclusive.”

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB121366164848479237.html

“Sen. Obama cited new economic forces to explain what appears like a return to an older-style big-government Democratic platform skeptical of market forces. “Globalization and technology and automation all weaken the position of workers,” he said, and a strong government hand is needed to assure that wealth is distributed more equitably.”

He doesn’t mention organized labor but he did during the recent jobs speech before Congress where he said nations shouldn’t compete in a race to the bottom. Now this is good rhetoric but I don’t know how much substance he has backed it up with.

Doug:

“So here’s the demand problem: there’s no longer an endless supply of easy credit to make up what’s not in the paycheck.”

Why can’t we have another bubble? Once deleveraging is complete won’t demand pick back up? And then another bout of “irrational exhuberance” as Greenspan put it.

Pingback: Counterparties: The Jetsons were Keynesians | Felix Salmon

Unemployment rates these days are so high. we really need some economic bailout. ‘

<a href="Newly released content coming from our new web site

http://www.melatoninfaq.com/melatonin-supplement/