The disappearing strike

According to Bureau of Labor Statistics figures released this morning, last year saw the second-smallest number of major strikes in recorded history: seven. This is close to the record low set in 2009, five—in the depths of the Great Recession, when the unemployment rate was approaching 10%. Last year’s average unemployment rate was less than half that, 4.3%.

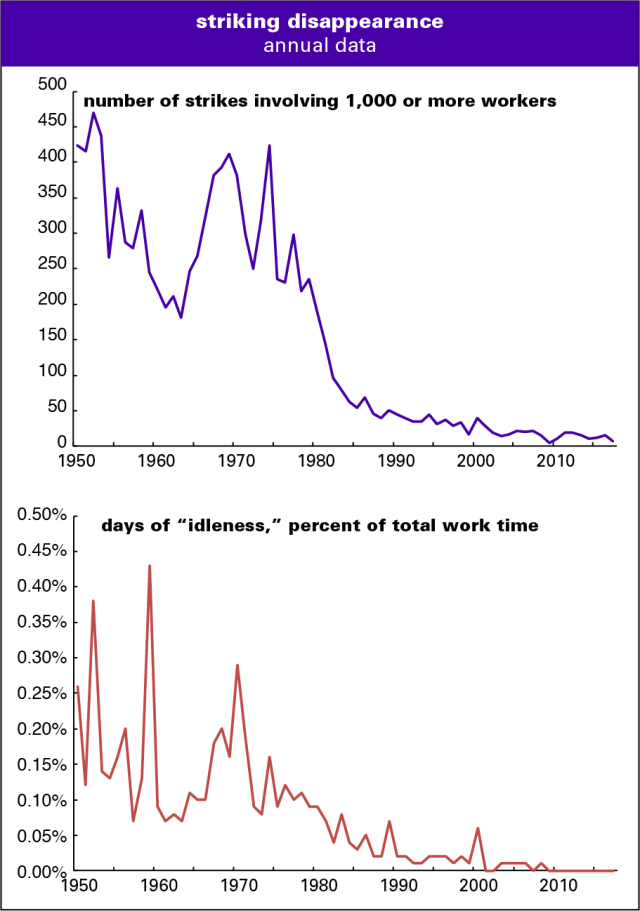

Here’s the grim history of the decline of labor’s most powerful weapon in two graphs:

The number of days of “idleness”—a curiously moralizing word for an instrument of class struggle—wasn’t as close to a record low. There were four years in which this measure (the number of workers involved times the length of the strike) was lower—all recent years (2009, 2010, 2013, 2014).

Between 1947 and 1979, there were an average of 303 “major” strikes (involving 1,000 or more workers) every year; since 2010, the average has been fourteen. The average number of days of “idleness” went from almost 24,550,000 in the first period to 708,000, a decline of 97%. This decline just might have something to do with stagnant wages, greater job instability, and disappearing benefits, though of course turning it around is a lot harder than writing an exhortatory blog post.

Most of those days off the job, 79% of them, came from just one strike, the IBEW‘s against Charter Communications, which is in its 318th day as I’m typing this. Just two other strikes were against private-sector employers (AT&T and car dealers in Chicago). One was against a university hospital system (Tufts—see Jane McAlevey’s article on that strike, one of the few inspiring stories in this bleak landscape, here). And three were against government employers, all in California (Riverside County, the City of Oakland, and the University of California). Private employers have absolutely no reason to worry about a strike, and haven’t for more than a decade. And when the Supreme Court hands down its decision in the Janus case, which will almost certainly eviscerate public sector unions, government employers are likely to feel the same way.

McAlevey’s mentor, Jerry Brown (the former president of 1199–New England, not the California politician), used to say the strike was like a muscle: if workers didn’t exercise it regularly, it would atrophy. It’s atrophied.

It’s a perverse problem. It’s hard to get workers to strike if they fear for their jobs and the gains from strikes are so often so low (especially since employers nowadays will pre-emptively lock out workers instead, even if it means they can’t hire permanent replacement workers), but without striking they won’t ever find the gains that are possible.

Strikes are down, crime is down, activism is down, both major parties are conservative or reactionary — this in a time when the lives of most of the people are growing worse and wealth and power disparities are increasing. There is little resistance of any kind. It’s very odd.

Reblogged this on 21st Century Theater.