Explaining the rot

In my article about fighting the coronavirus and economic crises yesterday, I said:

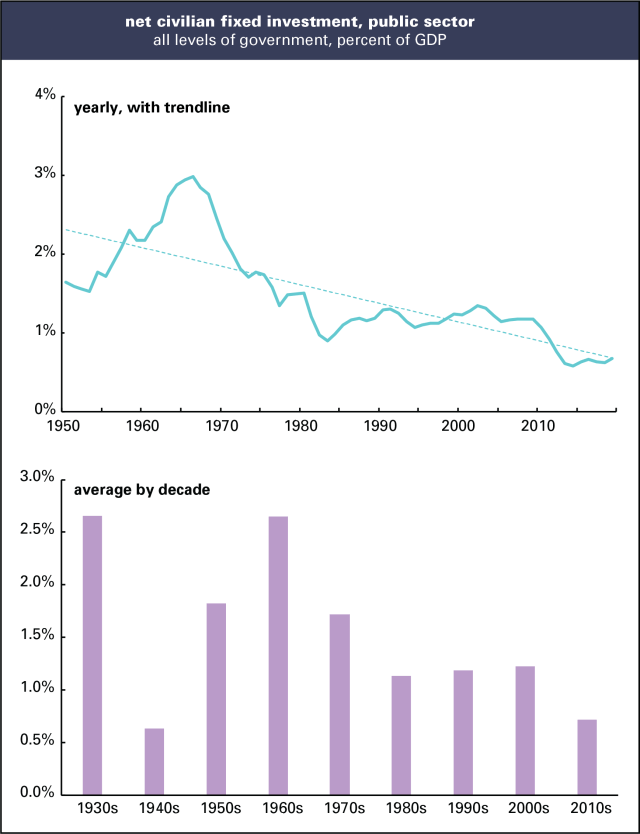

We also need to invest in the physical and social infrastructure of this country. For decades, civilian public investment net of depreciation has hovered just above 0, meaning that we’re doing little better than replacing things as they decay.

Here’s some more detail on that, which updates a September 2017 post.

Graphed below are histories of net public investment in the US, from the national income accounts. (The source is table 5.2.5, here.) “Net” means after accounting for depreciation, aka wear and tear. And public investment means government expenditures on long-lived assets like buildings, equipment, and roads. Not all of such expenditures are good. Prisons are in there, though they’re only a small portion of the total. But a robust public infrastructure is a foundation of a civilized life, and, as you can see, we’ve done little to build that foundation. It shows in collapsing bridges, dilapidated schools, and glaringly now, almost no public health system.

(I started the yearly graph in 1950, not 1929 when the national income accounts begin, because the figures for the Great Depression and World War II years would be distracting, but they’re captured in the decade averages.)

The New Deal saw a boom in public investment, creating an infrastructure we still use—bridges, schools, post offices, parks. (For details, see the Living New Deal site.) World War II resulted in a severe squeeze on public investment, taking it down from a peak of 3.2% of GDP in 1939 to zero and less during the war years. It recovered in the 1950s, and by the mid-1960s, came back almost to 1939 levels. That’s when the US was building schools, public universities, and the Interstate Highway system. (It wasn’t just federal spending—state and local governments were active builders as well.) It began falling in the 1970s and continued to fall in the 1980s and 1990s, the time of Reagan’s “government is the problem” and Clinton’s “the era of big government is over.” It stayed flat in the early 2000s, and in stark contrast with the 1930s, fell during the Great Recession and its aftermath. The reaction to that crisis, which took unemployment up to 10%, was austerity, not expansiveness. Public investment has ticked up slightly since, to 0.7% in 2019, which is also the average for the decade. That average is only 0.1 point above the 1940s, the years of world war.

It’s not just the federal government that’s been retrenching—it’s state and local as well. The 0.7% average for the decade is the sum of 0.6% at the state and local level and 0.1% at the federal. In other words, the federal government is barely keeping up with its infrastructure as it rots.

We badly need to turn this around with investments in old-fashioned things like schools as well as new ones, like clean energy generation and high-speed rail (which the private sector isn’t likely to produce on its own). A Green New Deal, in a phrase.