Fresh audio product

Just added to my radio archives:

March 10, 2012 Vijay Prashad on Syria, Libya, and why not to give up hope on the Arab Spring • Sean Jacobs on that Kony nonsense, African reality, and imperial designs

Credit union switch fizzles

Last fall, there was a lot of buzz about moving money out of banks and into credit unions. Grand claims were made about results. I had my doubts—politically (see here) and financially (see here). One can disagree with me on the politics, but it turns out that not much money was moved.

The Federal Reserve is out with its flow of funds accounts for the fourth quarter. These are a detailed accounting of assets, liabilities, and money flows throughout the U.S. financial system. And before anyone says that the Fed is lying to defend its Wall Street constituency, consider that the main audience for these accounts is banks and bourgeois economists. You could probably count the number of radicals who study these accounts seriously without taking off your shoes.

So, here’s the verdict. In the fourth quarter of last year, credit union deposits increased by $9.9 billion, or 1.2%. In the same quarter, commercial banks increased their checking and savings deposits by $232.2 billion, or 3.5%. The increase in bank deposits (and my measure of this excludes deposits exclusively used by large financial institutions) was 23 times the increase in credit union deposits.

And what did the credit unions do with their very modest windfall? They actually reduced their consumer lending (things like credit cards and auto loans). They increased their mortgage lending, but they increased their purchases of federal agency (e.g. Freddie Mac and Ginnie Mae) and Treasury bonds considerably more. They also increased their short-term lending to commercial banks via the federal funds market—in fact, more than a quarter of their increase went there. As I’ve said before, they already have more money than they know what to do with. Put your money in a credit union and it’s more likely than not to end up in very orthodox pursuits.

Sure, we need a better financial system. We need tighter regulation of the old one and new institutions that can lend preferentially to worker co-ops and other non-capitalist enterprises. But this credit union thing won’t cut the mustard. As I’ve said before, it’s a matter of politics, not individual portfolio allocation decisions.

The February job market: not bad by recent standards

And now for the major economic news of the week, the U.S. employment report for February. It was another solid affair—the third month in a row of over 200,000 job gains, with plenty of supporting details. I do have some worries about the quality of these new jobs, not to mention their durability, but for now things are looking better than they did even a few months ago.

The headline gain of 227,000 came with upward revisions of 61,000 to the back months (41,000 to January and 20,000 to February). Gains were widespread through the economic sectors. Manufacturing extended its impressive recovery, adding a very respectable 31,000 jobs, with what the Brits call the metal-bashing industries in the lead. Mining and logging were also strong, reflecting a little-noticed (and environmentally worrisome) increase in domestic U.S. energy production. (Factoid: North Dakota has lately been producing more oil than Ecuador, a member of OPEC. Transportation and finance were modestly in the plus column.) Temp firms, bars and restaurants, and health care posted strong gains—the first two tenuous and not-well-paying sectors; health care has some good jobs and some bad jobs mixed in. Retail and construction were lost workers, among the few sectors that did. Government job losses slowed considerably—local gov was even modestly in the black.

Despite those decent job gains, it’s important to point out that they’re slightly below the long-term historical average, including recessions. It’s about a third below the rate typically seen in expansions (leaving out recessions, that is). But considering how bad things have been, modestly subpar seems exuberant.

Average hourly earnings were up a very weak 0.1% for the fourth month in a row. For the year, hourly earnings were up 1.9%. They’ve been running between 1.8% and 2.0% for more than two years now—below the rate seen during the Great Recession, and barely keeping up with inflation. This weak growth rate suggests that low-wage jobs figure disproportionately figure in the recovery.

The figures I’ve been quoting come from the monthly survey of several hundred thousand employers. The BLS also does a simultaneous survey of about 60,000 households. It’s rich with demographic detail, but the smaller sample size makes it more error-prone, especially in the short term. But the establishment survey can miss new startups, which can be especially important in times of economic recovery. So disparities between the two surveys can be analytically interesting. This month, the household survey was considerably stronger than its establishment counterpart. Employment rose 428,000—or 879,000 when adjusted to match the payroll concept. The unemployment rate was unchanged, but only because of a significant influx of new and returning workers into the labor market. The number of job losers was down for the month. And the number of people quitting jobs voluntarilty rose. Clearly the public is feeling increasing confidence in the job market. “Hidden” unemployment measures were either flat or down. Those classed as not in the labor force but wanting a job now rose trivially, and those working part time for economic reasons fell strongly. The broadest measure of unemployment, U-6, which includes unwilling part-timers as well as those who’ve given up the job search as hopeless, fell 0.2 point to 14.9%. Though that’s still tragically high, it’s still this measure’s lowest level since February 2009.

Only the extreme duration of unemployment categories saw an increase – those jobless for less than 5 weeks, and those without work for 99 or more weeks. Though down from its highs, the number of long-term unemployed remains very sticky, which is both a serious social and economic problem, as millions hang on the margins with deteriorating skills and attachment. But the rise in the number of short-term unemployed is what you’d expect as frictional unemployment—people briefly unemployed between jobs—begins to take precedence over the recessionary kind.

More on the household survey’s outperformance. On one hand, it’s encouraging, and suggests that the payroll survey may be missing some business startups, as it often does early in recovery/expansion periods. But the adjusted household survey has been outperforming since 2006. It showed fewer job losses in the recession and has staged a stronger recovery over the last two years. While the missing new establishment story no doubt figures here, it’s also likely that some serious structural issues are at play.

For example, a 2009 NBER working paper (pdf) by Katharine Abraham, John Haltiwanger, Kristin Sandusky, and James Spletzer finds that workers at the demographic extremes are most likely to be categorized as employed in the household survey but not by the establishment survey. That is, poorly educated, immigrant, and minority workers are more likely than average to be employed off the books, and highly educated, skilled workers are more likely to be employed as independent contractors. Given employers’ reluctance to make lasting commitments these days, it’s quite likely that growth in these sorts of less-than-formal employment arrangements is an important factor in the labor market recovery (and also cushioned the recession’s blows). These are jobs, but not stable ones with benefits.

So, all in all, a decent employment report. But in 2010 and 2011 we saw a run of strength early in the year, followed by a deterioration as summer arrived. There was a similar pattern in 2004, but it did not repeat in 2005, as strength was sustained beyond spring. Perhaps this pattern of growth followed by a fade is a seasonal adjustment quirk, or a more structural feature of early recoveries. But maybe 2012 will be the year when recovery finally takes hold, and we can start putting all the post-crisis wobbliness behind us. Of course, we’ve still got over 5 million jobs to recover that we lost in the Great Recession, not even allowing for population increase. We also still have all kinds of long-term structural problems, like a lack of economic dynamism, polarization, a debt overhang. But things are getting better, slowly and tenuously better.

New data on student debt from the NY Fed

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York is out with some new data on student debt (“Grading Student Loans”). Two major highlights: beware of using simple averages, and, more strikingly, more than one in four borrowers is behind on payments—more than twice the share of other forms of personal debt.

First, the debt levels. Total student debt is about $870 billion—more than credit card balances ($693 billion) and auto loans ($730 billion). That’s an enormous number, but economists have paid it little attention—surprising, considering the attention paid to household finances. And student debt continues to rise, even though most other forms of personal debt are flat or even down, as consumers engage in the process that Wall Street likes to call “deleveraging.”

About 37 million people owe student loans, or 15% of the population. But the age profile of the debtors, not surprisingly, skews young. Over 40% of people in their 20s are on the hook, and 25% of those in their 30s. But just 7% of those 40 and over have student loan balances. Two-thirds of the debt is owed by people under 40, who are not known for their high incomes.

If you divide debt outstanding by the number of debtors, you get an average of $23,300. But that average is pulled upwards by a minority who are deeply in debt. The median debt is about half that mean, or $12,800. Here’s the New York Fed’s breakdown of the high-balance numbers:

About one-quarter of borrowers owe more than $28,000; about 10 percent of borrowers owe more than $54,000. The proportion of borrowers who owe more than $100,000 is 3.1 percent, and 0.45 percent of borrowers, or 167,000 people, owe more than $200,000.

Or, in a picture:

How are debtors doing in servicing the debt? On first glance, about 1 in 10 borrowers is behind on payments, which is about the same ballpark as credit cards, mortgages, and auto loans. But that first glance is very misleading because many borrowers—nearly half, in fact—are enjoying deferments until graduation and even grace periods beyond that. Adjusting for those, the New York Fed finds more than 1 in 4—27%—of borrowers at least one payment behind.

That’s an enormous level of distress—and it suggests than many more debtors are really stretching to make payments. And with debt levels rising, the level of distress isn’t likely to subside anytime soon.

As I wrote in LBO a while back (“How much does college cost, and why?”):

It would not be hard at all to make higher education completely free in the USA. It accounts for not quite 2% of GDP. The personal share, about 1% of GDP, is a third of the income of the richest 10,000 households in the U.S., or three months of Pentagon spending. It’s less than four months of what we waste on administrative costs by not having a single-payer health care finance system.

But we can’t do that—it’d be un-American.

Fresh audio content

Just posted to my radio archives:

March 3, 2012 Trudy Lieberman on health care reform so far • Yanis Varoufakis on the Greek debt deal and economic collapse

Morning again in America?

So it looks like Obama plans to sing from the Reagan songbook for his campaign—specifically from the “Morning in America” pages. In case you were too young the first time around, or now are too old to remember, the original went something like this:

The logic is this: Reagan got re-elected during the recovery after a deep recession, so Obama can do the same. Also, Reagan whipped Grenada’s ass and Obama killed Osama.

Foreign victories don’t count for much in election campaigns but economic conditions count a lot. So how bright is Obama’s morning compared to Reagan’s?

TPM took a look at this question earlier today (Is It Morning — Or Dawn — In America?), but in a very incomplete way. Here’s a broader look. And the answer is: not as bright as 1984, actually.

For most people, what matters most is the job market. And today’s job market lags 1984’s.

First, total employment.

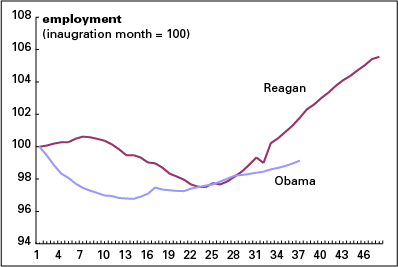

Both presidents endured sharp hits to employment (though for Obama, the declines extended those of his predecessor). Obama’s hit was earlier and deeper than Reagan’s. But Obama’s recovery has been weaker. By Reagan’s 37th month in office, employment was nearly 2% above where it was when he was inaugurated; for Obama, employment is still down almost 1%.

Now unemployment.

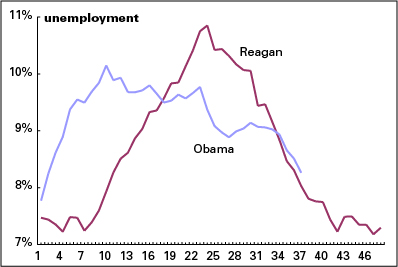

Reagan suffered a higher and later peak in unemployment (10.8% in month 23, compared to Obama’s 10.1% in month 10), but enjoyed a much steeper drop. As of the 37th month, Reagan’s unemployment rate was 8.0%, a decline of 2.4 points from a year earlier. Obama’s 8.3% is just 0.8 point down from a year earlier. And Obama’s unemployment rate is worse than it looks, since vast numbers of people have dropped out of the labor force and therefore aren’t counted as unemployed. In the year before Reagan’s 37th month, the participation rate—the employed plus the unemployed as a share of the adult population—rose by 0.1 point, as people were drawn into an improving job market. Obama’s, however, is off by 0.5 point, as people discouraged by job prospects give up on the search.

As LBO has shown in the past, you can explain most post-World War 2 presidential elections using a model consisting of just two variables—inflation-adjusted after-tax income per capita and presidential approval. If income is positive and approval over 50%, the incumbent or another member of his party is highly likely to win. Things are not looking so good for Obama on that score—though the model is best when run with numbers for the spring, not the late winter, so let’s hold off on predictions for a few months.

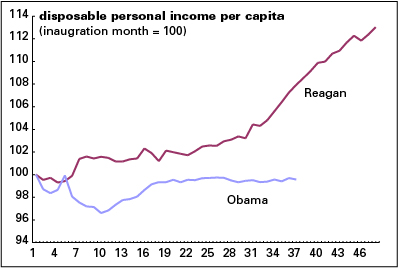

Here’s the income comparison. (Officially the measure is known as real disposable personal income [DPI] per capita.)

DPI took a much sharper hit under Obama than Reagan, and has been flat for a year-and-a-half. DPI is still 0.4% below where it was when Obama took the oath of office. The comparable figure for Reagan is up nearly 8%. DPI is an average, and can be distorted upwards by action at the high end, but it’s still a decent broad measure, and by that measure, Obama’s doing very badly. (Not that it’s his personal fault, of course.)

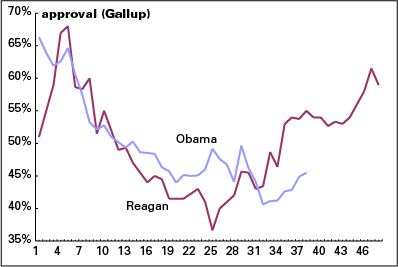

And how about approval? On that, Obama’s doing a little better than might be expected given those crummy income numbers—but still, Reagan was 9 points ahead of Obama (54% vs. 45%). And Reagan was up 17 points over the previous year—Obama’s down 4.

So is it morning once again in America? Not really. Predawn maybe.

New radio product

Freshly posted to my radio archives:

back after KPFA fundraising hiatus—if you like this show, please support the station now! and mention Behind the News if you do—there’s a best of BtN premium, consisting of 26 of my best interviews of the last decade, available for a pledge of $75

Gary Weiss, author of Ayn Rand Nation, on her cult and influence • Adolph Reed on Black History Month, the return of the ghoulish Charles Murray, and politics in gloomy times

Austerity & bankers’ coups: the NYC precedent

With the displacement of Greece’s elected government by Eurocrats acting in the interest of the country’s creditors, I thought this would be a good time to reprise the section of my 1997 book Wall Street that covers the New York City fiscal crisis of 1975, which was something of a dress rehearsal for the neoliberal austerity agenda that would go global in the 1980s. Certain celebrity academics are constantly cited for making this argument, but I was there first. You can download Wall Street for free by clicking here: Wall Street.

This chapter, and this book, has mainly been about the private sector, but it would be incomplete to finish a chapter on “governance” without looking at the relations between Wall Street and government, not only in the U.S., but on a world scale.

One advantage that Wall Street has in public economic debate, aside of course from its immense wealth and power, is that it’s one of the few institutions that look at the economy as a whole. American economic policymaking is, like all the other kinds, largely the result of a clash of interest groups, with every trade association pleading its own special case. Wall Streeters care, or presume to care, about how all the pieces come together into a macroeconomy. The broadest policy techniques—fiscal and monetary policy—are what Wall Street is all about. For some reason, intellectuals like the editors of the New York Review of Books and the Atlantic have decided that investment bankers like Felix Rohatyn and Peter Peterson have thoughts worth reading in essay form. Not surprisingly, both utter a message of austerity—the first with a liberal, and the second with a conservative, spin—hidden behind a rhetoric of economic necessity. These banker–philosophes, creatures of the most overpaid branch of business enterprise, are miraculously presented as disinterested policy analysts.

Wall Street’s power becomes especially visible during fiscal crises, domestic and international. On a world scale, the international debt crisis of the 1980s seemed for a while like it might bring down the global financial system, but as it often does, finance was able to turn a crisis to its own advantage.

While easy access to commercial bank loans in the 1970s and early 1980s allowed countries some freedom in designing their economic policies (much of it misused, some of it not), the outbreak of the debt crisis in 1982 changed everything. In the words of Jerome I. Levinson (1992), a former official of the Inter-American Development Bank:

[To] the U.S. Treasury staff…the debt crisis afforded an unparalleled opportunity to achieve, in the debtor countries, the structural reforms favored by the Reagan administration. The core of these reforms was a commitment on the part of the debtor countries to reduce the role of the public sector as a vehicle for economic and social development and rely more on market forces and private enterprise, domestic and foreign.

Levinson’s analysis is seconded by Sir William Ryrie (1992), executive vice president of the International Finance Corporation, the World Bank’s private sector arm. “The debt crisis could be seen as a blessing in disguise,” he said, though admittedly the disguise “was a heavy one.” It forced the end to “bankrupt” strategies like import substitution and protectionism, which hoped, by restricting imports, to nurture the development of domestic industries. “Much of the private capital that is once again flowing to Latin America is capital invested abroad during the run-up to the debt crisis. As much as 40–50 cents of ever dollar borrowed during the 1970s and early 1980s…may have been invested abroad. This money is now coming back on a significant scale, especially in Mexico and Argentina.” In other words, much of the borrowed money was skimmed by ruling elites, parked profitably in the Cayman Islands and Zürich, and Third World governments were left with the bill. When the policy environment changed, some of the money came back home — often to buy newly privatized state assets for a song.

That millions suffered to service these debts seems to matter little to Ryrie. Desperate Southern governments had little choice but to yield to Northern bankers and bureaucrats. Import substitution was dropped, state enterprises were privatized, and borders made porous to foreign investment. After Ryrie’s celebrated capital inflow, Mexico suffered another debt crisis in 1994 and 1995, which was “solved” using U.S. government and IMF guarantees to bail out Wall Street banks and their clients, and creating a deep depression; to make the debts good, Mexicans would have to suffer. Once again, a dire financial/fiscal crisis—the insolvency of an overindebted Mexican government—was used to further a capital-friendly economic agenda.

These fortunate uses of crisis first appeared in their modern form during New York City’s bankruptcy workout of 1975. This is no place to review the whole crisis; let it just be said that suddenly the city found its bankers no longer willing to roll over old debt and extend fresh credits. The city, broke, could not pay. In the name of fiscal rectitude, public services were cut and real fiscal power was turned over to two state agencies, the Municipal Assistance Corp. (MAC, chaired by Rohatyn), and the Emergency Financial Control Board, since made permanent with the Emergency dropped from its name. Aside from the most routine municipal functions, the city no longer governed itself; a committee of bankers and their delegates did, Rohatyn first among them. Rohatyn, who would later criticize Reaganism for being too harsh, was the director of its dress rehearsal in New York City. Public services were cut, workers laid off, and the physical and social infrastructure left to rot. But the bonds, thank god, were paid, though not without a little melodrama, gimmickry, and delay (Lichten 1986, chap. 6).

The city was admittedly borrowing irresponsibly—though the lenders, it must be said, were lending irresponsibly as well. When a bubble is building, neither side has an incentive to stop its inflation. But when it broke, all the pain of adjustment fell on the citizen–debtors. The pattern would be repeated in the Third World debt crisis, in many U.S. cities over the next 20 years, and, most recently, with the federal budget.

Obviously the bankers have the advantage in a debt crisis; they hold the key to the release of the next post-crisis round of finance. Anyone who wants to borrow again, and that includes nearly everyone, must go along. But that’s not their only advantage. The sources of their power were cited by Jac Friedgut of Citibank (ibid., p. 192):

We [the banks] had two advantages [over the unions]…. One is that since we were dealing on our home turf in terms of finances, we knew basically what we were talking about, and we knew and had a better idea what it takes to reopen the market or sell this bond or that bond…. The second advantage is that we do have a certain noblesse oblige or tight and firm discipline. So that we could marshal our forces, and when we spoke to the city or the unions we could speak as one voice…. Once a certain basic process has been established that’s an environment in which our intellectual leadership…can be tolerated or recognized…we’re able to get things effected.

It’s plain from Friedgut’s remarkably candid language that to counter this, one needs expertise, discipline, and the nerve and organization to challenge the “intellectual leadership” of such supremely self-interested parties. According to the union boss Victor Gotbaum (in an interview with Robert Fitch, which Fitch relayed to me), the unions’ main expert at the time, Jack Bigel, didn’t understand the budgetary issues at all, and deferred to Rohatyn, whom he trusted to do the right thing. For the services rendered to municipal labor, the once-Communist Bigel was paid some $750,000 a year, enough to buy himself a posh Fifth Avenue duplex (Zweig 1996). Gotbaum became a close friend of Felix Rohatyn. Politically, the unions were weak, divided, self-protective, unimaginative, and with no political ties to ordinary New Yorkers. It’s easy to see why the bankers won.

What was at stake in New York was no mere bond market concern. In a classic 1976 New York Times op-ed piece, L.D. Solomon, then publisher of New York Affairs, wrote: “Whether or not the promises…of the 1960’s can be rolled back…without violent social upheaval is being tested in New York City…. If New York is able to offer reduced social services without civil disorder, it will prove that it can be done in the most difficult environment in the nation.” Thankfully, Solomon concluded, “the poor have a great capcity for hardship” (quoted in Henwood 1991).

Behind a “fiscal crisis” lurked an entire class agenda, and one that has been quite successfully prosecuted in subsequent crises for the next two decades. But since these are fought on the bankers’ terrain, using their language, they instantly win the political advantage, as nonbankers retreat in confusion, despair, or boredom in the face of all those damned numbers.

How to stop worrying about class

Today’s New York Times contains a fine example of how ideology works at the high end: report information that might trouble the established order, but conclude on a tranquilizing note that allows the comfortable reader to turn the page (or click “close tab”) without changing his or her worldview. Both functions are important. Outlets like the Times do report tons of important stuff that one would be hard-pressed to learn otherwise. But, as Alexander Cockburn put it long ago, a primary function of the bourgeois press is reassurance.

The piece by Sabrina Tavernise, “Education Gap Grows Between Rich and Poor, Studies Show,” shows that “while the achievement gap between white and black students has narrowed significantly over the past few decades, the gap between rich and poor students has grown substantially during the same period.” (The paper from which much of the data is drawn, by Stanford sociologist Sean Reardon, can be gotten here.) While it’s long been well known that parental income and education have a stronger influence on educational outcomes than schools themselves, the gap between kids from affluent and poor families is widening.

All that information, and then some, is nicely presented in the first half of the article. But the second half consists mostly of quotes from three right-wing sources: University of Chicago labor economist James Heckman; Bell Curve ghoul Charles Murray (newly famous for his cultural take on the crisis of the white working class); and Douglas Besharov, now of the Atlantic Institute but formerly of the American Enterprise Institute, where he ran the Social and Individual Responsibility Project. Heckman says the last thing we should do is give poor people more money. Murray says it has “nothing to do with money and everything to do with culture.” And Besharov chimes in with the inevitable “no easy answers,” because “no one has the slightest idea what will work.”

Nonsense. The answers are conceptually easy, though politically anything but. You take money from rich people and give it to poor people, and spend at least as much, maybe more, educating the children of the poor as you do on the children of the rich. But that might make the Times’ audience uncomfortable. Better to flatter them on their excellent parenting.

Disclosure alert: I know Sabrina Tavernise and like her a lot. I just wish she’d written this piece differently.

Reflections on the current disorder

This is the text of the talks I gave at the University of California–Riverside and UC–Irvine, January 25 and 26, 2012. Graphs were added for the bloggy version.

It’s funny. I spend most of my life writing about economics, politics, and finance, yet about the only academics who ever invite me to speak are in the humanities. Maybe that’s because I dropped out of a graduate English program and can’t do a proper vector autoregression. But you guys are more fun than a bunch of dismal scientists anyway.

I took my title, “Reflections on the Current Disorder,” from William F. Buckley, who used it as an all-purpose label for his public talks back in the 1970s. Though it might seem odd for me, a non-conservative, to borrow a title from a paragon of American conservatism—one whose memory is fading, for sure, in these days of Fox News and Newt Gingrich—I was once a fan. In fact, I was once a conservative, for a year or two in the early 1970s. I was even a member of a strange formation called the Party of the Right in my early college days, a group that opens its meetings by reciting Charles I’s execution speech, which contains the striking revelation that government is no business of the people, because “a subject and a sovereign are clean different things.” (See here and here for more.) You may think that the U.S. fought a revolution against monarchy, but nostalgias for hereditary power still exist on the American right. Feel free to bring that up next time a Republican tells you that leftists are unpatriotic elitists.

Anyway, Chairman Bill and I have different feelings about the idea of disorder, I suspect. (Though my friend Corey Robin argues in his new book, The Conservative Mind, that rightists are often revolutionary nihilists under their placid exteriors.) But the present state of the U.S. economy is a wreck. For most people these day it’s a source of misery at worst or profound uncertainty at best. I suppose there are more than a few right-wingers who have no fundamental problem with this. You never have to wait very long for some apologist to cite Joseph Schumpeter’s famous phrase “creative destruction,” a phrase that gets 1.3 million hits on Google. Also, according to Google, use of that phrase really started to take off with the onset of the neoliberal era in the early 1980s, peaking into the dot.com bubble and its immediate aftermath around 2002, and then falling slightly into 2008 (when their ngram database ends).

A major problem with the phrase, aside from its unconcern (or at least its users’ unconcern) with the human distress associated with it—not to mention its indifference to Schumpeter’s original use, a Marx-inspired view of capitalism’s eventual demise—is that not much creation has been going on lately. I’m not talking about works of art, but conventional economic innovation—which may be going on in China, but sure isn’t going on here in the USA in any quantity.

Throughout our history, this has been a brutal society, but at least it had a certain dynamism in both commerce and in culture. I don’t see much of that today. The last gasp of economic dynamism was that dot.com boom, which was often thoroughly delusional, but did have some energy to it, and did leave us some byproducts, like many miles of fiber optic cable. It also paradoxically presumed to address some concerns historically associated with the left—a flattening of hierarchies, the provision of meaningful work, the erasure of borders, and even peace, love, and understanding. Of course it did all that firmly within a capitalist paradigm, but it did have an embryonic aspect about it, if only in fantasy. No longer. Our most recent bubble built a lot of subdivisions in exurban Las Vegas, with no payoff either in the productive or phantasmic realms. There might be some payoff were the homeless and underhoused allowed to move into the empty dwellings, but that’s not the way the USA works—though the Occupy movement seems to be nudging things in that direction.

So where are we, political economy-wise. Here are our coordinates in vulgar business-cycle terms. The Great Recession officially ended more than two and a half years ago, and to most people it doesn’t feel like much of a recovery.

savage recession…

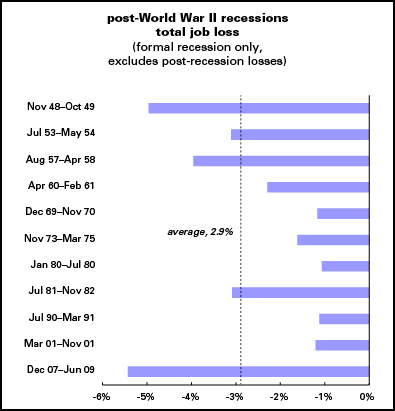

It was an awful recession. GDP, your orthodox economist’s favorite measure, contracted by over 4%, more than twice post-World War II recession average. The downturn officially lasted six quarters, a year and a half, two quarters longer than the average. Employment, the measure that matters most to regular people, fell by over 5%, almost twice the post-World War II average—and then fell by another 1% after the recession ended.

The reason that it doesn’t feel to many people like the recession never ended is that it’s been the weakest recovery since modern GDP numbers begin in 1929 and modern labor market numbers in 1939. As of the most recent quarter, the third of 2011, GDP, that most fetishized of all indicators, has only regained its pre-recession high; based on historical averages, it “should” be about 10% above. Total wage and salary income is about 2% below its pre-recession high; normally, it’d be up 13%. Ah, but profits! Corporate profits are up over 80% from their recession low; normally they’d be up about 50%. Profits are up nearly ten times as much as wages—the average in a recovery would be less than three times. Corporations are flush with cash—they’re spending some of it abroad and distributing some of it to their shareholders and executives. What they’re not doing is investing or hiring here.

The labor market, which is what most people depend on for their material welfare (about 80% of the population couldn’t live more than a few months without a paycheck at best), is a mess. We lost nearly 9 million jobs in the recession (actually we continued to lose jobs after the recession ended, well over a million of them) and have regained well under a third of them. In a normal post-World War II recovery, we would have regained those job losses in less than a year and would now be well ahead of the pre-recession high. If this were that elusive normal recovery, nearly 7 million more people would be employed now than are.

Yes, the unemployment rate has come down—in part because of the modest recovery we’ve experienced, but also because enormous numbers of people have dropped out of the labor force. If you’re not actively looking for work, you’re not counted as unemployed; if you haven’t looked for a job in the last year, you’re not even counted as “discouraged,” the official label for that brand of labor-market detachment. The share of the adult population working for pay, the so-called employment/population ratio, is exactly where it was when employment bottomed out in February 2010. It’s below where it was when the recession ended. It’s well below its all-time peak in 2000–2001. Over the long haul, the employment/pop ratio had risen steadily into that millennial peak, mainly because of the entry of women into the paid labor force. The male ratio had already been in a mild but steady decline since the end of World War II but its fall was more than offset by the rise in the female ratio.

The ratios for both sexes plunged during the recession, men’s worse than women’s, and have basically just stabilized over the last couple of years. Men have actually done a little better than women—the result, I suspect, of a surprisingly decent recovery in manufacturing employment (dispoportionately good for men) and the shrinkage in government employment (bad for women). The overall employment/population ratio is back where it was in 1983, meaning that the entire employment expansion of the 1980s and 1990s has been reversed.

At recent rates of job creation, it would take about five years to recover the jobs we lost, and that’s not allowing for population growth. If the population continues to grow at recent rates, it would take well over eight years.

Sad to say, none of this is really a surprise. the economy and job market are following the script of a post-financial-crisis recession almost perfectly: they take years to recover from.

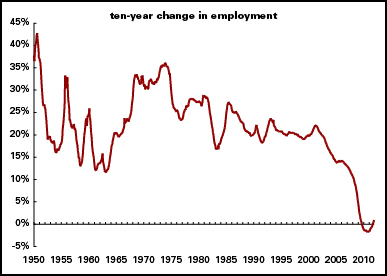

…after a weak expansion

But, as they say on TV, that’s not all. The 2002–2007 expansion was the weakest one in modern history. Jobs were created at a rate that was about a third the average of the post-World War II expansion. The combination of that tepid expansion, which was preceded by a long period of job market weakness, and the Great Recession, meant that employment from late 2009 through late 2011 was actually lower than it was ten years ealier—2% lower at its worst Since the 1930s, there had never been a period in which employment in the U.S. contracted over the course of a decade. The worst previous ten-year reading since the 1930s was a gain of 22% over ten years. We’re now recovered to where we’re not quite 1% above where we were ten years ago. That contrast is really striking: 22% previous worst, vs. an actual decline of about 3%.Back in the 1990s, cheerleaders used to love to talk about the Great American Job Machine. That machine has clearly popped a few gaskets.

origins

So how’d we get into this mess? We all know the story of the proximate causes of the economic crisis—a housing bubble enabled by not merely massive applications of credit, but credit packaged in unimaginably complex and obscure forms and a dispersion of responsibility that comes with securitization. There was a synergy of troublemaking here. Mortgage debt, after rising gently through the 1980s and 1990s, exploded after 2000. We know that lending standards deteriorated, to where the only requirement for getting a loan was having a pulse—and I bet you could even find some exceptions to that rule. (Some of that credit laxity may be coming back—my kid got a credit card solicitation a couple of months ago, well before his sixth birthday.) Downpayments became optional. The habit of packaging mortgages into bonds and selling them to distant investors removed any incentive for the original lender to scrutinize the creditworthiness of borrowers—and allowed trouble to proliferate around the world when things went bad.

My use of the word “bond” in the last sentence is as quaint as downpayment became, because the finest minds of Wall Street assembled all manner of mortgages into complex derivatives that no one, even some of the people who sold them, could understand. (Ok, “no one” is an exaggeration. I think the actual count of people who undersood these derivatives was in the hundreds.) Investors had absolutely no idea what horrors were hidden in the structured products they bought, even though many came with a Aaa ratiing. Either the rating agencies didn’t know what they were grading or didn’t care—the issuers of the dodgy securities were the one who were paying their fees; as one rater put it in a famous email, they’d rate things put together by cows. Of course they weren’t put together by cows—the were put together by investment bankers, who are far more dangerous.

further back

All this is true. But it’s a mistake to look only at that part of the story. Today’s crisis also has a prehistory going back to the problems of the 1970s and the neoliberal prescription for fixing those problems.

The “problem” of the 1970s was, of course, stagflation—stag as in stagnation, and flation as in inflation. The stag part is actually rather misleading; the expansion of the Carter expansion saw job growth four times as rapid as that of the George W. Bush expansion, and GDP growth half again as high. For the whole decade, GDP growth in the 1970s was also half again as high as so far in the 2000s—but such a comparison for employment is near impossible, since job growth in this decade is close to 0.

Note that job growth was far stronger relative to GDP growth in the Carter years than the W years. That gives a hint of the contrasting class dynamics of the two eras: labor got a much bigger share of the action in the much-criticized 1970s than it has lately, which is a clue to why it’s so fashionable to make fun of the decade, aside from its strange fashions.

But the inflation part of the 1970s was important. The CPI maxed out at nearly 15% in 1980, and hit an 18% annualized rate in March of that year. Wartime inflations were common in U.S. history, but never this chronic and deteriorating sort of thing.

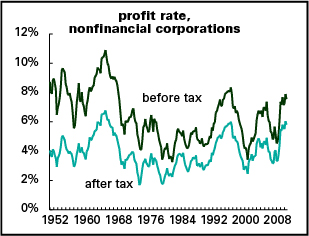

Inflation wasn’t just about rising prices—it was also about sagging productivity, falling profitability, limp financial markets, and, less quantifiably, a general loss of discipline in the workplace and the erosion of American power in the world. Corporate profitability, which had peaked at 11% in 1966, fell by two-thirds to under 4% in 1980. With high inflation, holding bonds became a losing proposition; Treasury bonds were nicknamed certificates of confiscation. Stocks turned in one of their worst decades ever—not as bad as the 1930s, but close.

But it wasn’t just a matter of numerical indicators. The U.S. lost the Vietnam War, and oil and other commodity exporters were jacking up prices, and the Third World was demanding redistribution on a global scale. Though it’s largely forgotten now, the working class was restive and rebellious. Formal strikes were common (as they were in the 1950s and 1960s), but so were the wildcat kind. Back in 1970, Richard Nixon called out the National Guard to deliver the mail because postal workers went on a self-organized strike (they had no union). Later in the decade, we heard a lot about the blue-collar blues, and in 1978, the appropriately named country singer Johnny Paycheck scored a hit with “Take This Job and Shove It.”

the crackdown

Obviously something had to give, and what gave was the working class, domeestically and internationally. Paul Volcker came into office in October 1979 declaring that the American standard of living had to decline, and he made it happen by driving up interest rates towards 20% and creating the deepest recession since the 1930s. (We just beat that record, but it took 30 years!) To the one-sided class war, Reagan added the ammunition of firing the air traffic controllers—the very opposite of what a Republican president had done with strikers only a decade earlier—and it was open season on organized labor. Wages and social spending were squeezed, and the deregulatory agenda that began under Carter was intensified. Abroad, Latin America was thrown into debt crisis, a crisis that for a while threatened to take down the global banking system—but instead, the problem was solved through the now-familiar neoliberal agenda of privatization and opening up to cross-border trade and financial flows. Debtor countries were forced to dismantle their nationalist–protectionist development regimes as a condition of new finance, and to open to foreign trade and capital flows.

The program was very successful. Internationally, Latin and other debtor countries were brought into the global flow of goods and money. Domestically, the recession scared the hell out of the working class; people were glad to have a job, and wouldn’t dream of telling anyone to shove it. Business became essentially free to do whatever the hell it wanted to. Profitability recovered strongly, rising throughout the 1980s and 1990s to a peak of over 8% in 1997—not quite 1966 levels, but still more than twice the trough of 15 years earlier. It took a while, but productivity finally joined in. In the military–political sphere, U.S. power was enhanced, and we kicked the Vietnam Syndrome too. Discipline problems were a thing of the past.

There were a few interruptions—a stock market crash in 1987 that looked scary for a while, a long stagnation and jobless recovery in the early 1990s, the bursting of the dot.com bubble ten years later. But all in all, the system managed to recover from, even thrive, on its troubles, and state managers perfected their bailout techniques. Of course, each bailout laid the groundwork for the next bubble, but Alan Greenspan famously said that one needn’t worry about bubbles because one can always repair the damage after the fact. He lately seems chastened on that topic.

the contradictions

But through those bubbles, busts, and recoveries, one constant persisted. A system dependent on high levels of mass consumption has a hard time living with a prolonged wage squeeze. I mean that not only in the economic sense, but also a political/cultural one. American life is very insecure and volatile, and the ability to buy lots of gadgets assuages that to a considerable degree. Mass consumption staves off what could be a serious legitimation cdrisis. For the last few decades, the economic and political contradiction has been managed, if not resolved (not that it could ever be) through the liberal use of debt—credit cards at first, and then mortgages from the mid-1990s onward. The explosion in household credit —from 65% of disposable income in 1983 to 135% at the 2007 peak (most of it from mortgages, by the way)—is what made the booms and bubbles of the last three decades possible. This is especially true of the 2001–2007 expansion, which featured the slowest employment and aggregate wage growth of any cycle since numbers the numbers begin in 1929. Without the massive cashing in on appreciating home equity—Americans withdrew several trillion dollars worth of home equity during the decade of boom, all of it borrowed against rising house values that would soon go into reverse, and spent much of it—consumption would have languished and the home improvement business would have gone under (since home improvements during the bubble were financed almost exclusively by equity withdrawals). And since we have almost no domestic savings, much of the cash for that adventure came from abroad, from places like the People’s Bank of China.

Lest you think that this analysis, tying debt growth to increased inequality, is just the fevered product of a radical mind, let me assure you that it recently got support from a very orthodox corner. A bit over a year ago, the International Monetary Fund—normally thought of as a bastion of economic orthodoxy—published a working paper with the provocative (by IMF standards) title “Inequality, Leverage and Crises.”

In any case, in the paper, IMF economists Michael Kumhof and Romain Rancière wondered aloud whether the increase in inequality we’ve seen over the last few decades contributed anything to the causes of our economic crisis. They attempt to model, in rigorous mathematical fashion, the perception that poor and middle-income households borrowed aggressively to maintain or expand their standard of living while wages and employment were growing only weakly, at the same time that rich households had more money than they knew what to do with, so they sought profitable opportunities to lend all that spare cash to those below them on the income ladder.

Kumhof and Rancière draw parallels between the recent period and the 1920s. In both periods, the share of income claimed by the top 5% rose dramatically, and by similar magnitudes. And during the 1920s and the recent period, roughly the last 25 years, the ratio of household debt to underlying incomes doubled.

Sometimes conservatives defend income inequality in the U.S. by appeals to our instinctive but untested assumptions about mobility. That is, the alleged ability of people to raise their incomes over time, over that of their parent or their own young selves, is thought to compensate for the high levels of inequality at any one moment. But actually this excuse doesn’t hold water. The U.S. is no more mobile, and is often less so, than other rich countries; that is, people here are no more likely, and are often less likely, to surpass the income levels of their parents than they are in Western Europe. And the U.S. today is, if anything, less mobile than it was a few decades ago.

And over the last 25–30 years, nonrich households have increased their indebtedness far more than those at the top. Back in 1983, the richest 5% were significantly more indebted, measured relative to their incomes, than the bottom 95%. That position has since reversed. So almost all of the increase in U.S. debt ratios—a household debt level of not quite 70% in 1983 compared with 135% at the peak in 2007, a near-doubling—has come from the nonrich portion of the population.

At the same time, the financial sector has grown enormously (more on this in a moment). A major reason for this growth has been its arrangement of all that borrowing and lending between the capital-owning class (the top 5%) and the bottom 95%, the workers. By the way, despite the Marxish cast of these labels, they come from the IMF economists, not me.

We don’t have the same sort of detailed statistics covering the 1920s, but the broad outline is very similar: polarization offset by increased borrowing, followed by a major financial crisis.

way out

In their analysis, Kumhof and Rancière, following the argument of the IMF’s former top economist, Rajuran Rajan, “that growing income inequality [and I’m quoting them, not me] created political pressure—not to reverse that inequality, but instead to encourage easy credit to keep demand and job creation robust despite stagnating incomes.” So what is to be done in the face of this?

Kumhof and Rancière, quite plausibly, say there are only two ways of dealing with our present pickle. On the one hand, we can have an orderly debt reduction—a policy of slow and careful writeoffs and debt forgiveness rather than massive default leading to financial crisis. Well, we’ve already had some of that, and we’ve made more than a dent household debt levels, but the result has been a rather glum economy.

A second possiblity is, of course, as Kumhof and Rancière put it, “a restoration of workers’ earnings—for example, by strengthening collective bargaining rights.” That is, raise wages and strengthen union power. In the recent political environment, that looks like a tall order, but maybe things are changing.

Kumhof and Rancière acknowledge the political obstacles to the wage-raising strategy. But, as they put it in that gentle and sober way that mainstream types are fond of, “the difficulties of doing so must be weighed against the potentially disastrous consequences of further deep financial and real crises if current trends continue. Restoring equality by redistributing income from the rich to the poor would not only please the Robin Hoods of the world, but could also help save the global economy from another major crisis.” I should point out that this paper was a product of an IMF run by the French quasi-socialist, Dominique Strauss-Kahn, who ran into a bit of trouble in a New York hotel.

financial hypertrophy

I quoted that IMF paper as noting the enormous increase in the size of the financial sector. I’d like to say a few words about that. I’d thought that the financial crisis that began in 2007 and got truly awful in 2008 would put an end to the long rise of the financial sector in the U.S. economy. Maybe not lead to a major political transformation, but at least some downward adjustment to Wall Street’s enormous economic and political power.

Didn’t happen, did it? If anything, Wall Street has used the crisis if not to enhance its power at least to demonstrate it.

There are several dimensions to Wall Street’s rise to pre-eminence over the last few decades. One can simply be measured in money. For example, in almost every year since the U.S. national income accounts begin in 1929, securities and commodities brokers have been the highest-paid of almost the almost 90 industries reported by the Bureau of Economic Analysis. And the securities industry’s premium has grown enormously over time. From 1929 through 1939, it was 237% of average pay. It fell during World War II and the immediate postwar decades, at just under 180% of average pay. But with the takeoff of the bull market in 1982, the premium began to swell, crossing 300% in 1992 and 400% in 2006. It fell back some in 2008, to a mere 409%. It fell back some more in 2009 to 366%, which, though below the massive heights of a few years ago, is still higher than anything before 2004.

Or take profits. As the bull market was about to take off in 1982, the financial sector claimed 12% of pretax profits in 1982; that nearly tripled to 34% at the 2008 peak. It fell by more than half in the heat of the crisis, to 15% at the end of 2008—but it back to nearly 30%. That’s a remarkable share for a sector that employs less than 6% of the workforce.

Or take the proliferation of assets. Financial assets of all kinds—not just debt, but equities and everything else the Federal Reserve counts in its flow of funds accounts—were equal to 462% of GDP in 1982. That measure rose steadily for the next 25 years, more than doubling to a peak of 1,058% of GDP in 2007. The ratio came down a bit with the early stages of the financial crisis, but bottomed in the first quarter of 2009 and has been more or less flat ever since.

So here’s the story the numbers tell us: after a long period, mainly the Golden Age of the post-World War II decades through the 1970s, Wall Street was something of a torpid backwater. Its denizens lived well, but not large. But since then, they’ve accumulated an enormous amount of wealth.

Then there’s the issue of power. The financial sector has surprisingly little to do with raising money to finance real corporate investment. It rarely has. That’s especially true of the stock market. Even in the boomiest moments of the late 1990s dot.com bubble, IPOs—first offerings of stock to public investors—financed only a small fraction of corporate investment, about 5–6%.

Or, looked at another way, if you combine net equity offerings—which, given the heavy schedule of buybacks over the last quarter century, have been negative most of the time since 1982—takeovers (which involve the distribution of corporate cash to shareholders of the target firm), and traditional dividends into a concept I call transfers to shareholders, you see that corporations have been shoveling cash into Wall Street’s pockets at a furious pace. Back in the 1950s and 1960s, nonfinancial corporations distributed about 20% of their profits to shareholders. In the 1970s, that fell to 15%, which helped create the sour mood on Wall Street in that decade. After 1982, though, the shareholders’ share rose steadily. It came close to 100% in 1998, fell back to a mere 25% in 2002, and then soared to 126% in 2007. That means that corporations were actually borrowing to fund these transfers. It fell during the crisis, bottoming at 21% in mid-2009, but as of late last year, it was almost 70%.

Businesses do get outside financing, yes, but the most important source of that is old-style banks. So what exactly does Wall Street do? Let’s be generous and concede that it does provide some financing for investment. But an enormous apparatus of trading has grown up around it—not merely trading in certificates, but in control over entire corporations. I think it’s less fruitful to think of Wall Street as a financial intermediary than it is to think of it as an instrument for the establishment and exercise of class power. It’s the means by which an owning class forms itself, particularly the stock market. It allows the rich to own pieces of the productive assets of an entire economy. So, while at first glance, the tangential relation of Wall Street, especially the stock market, to financing real investment might make the sector seem ripe for tight regulation and heavy taxation, its centrality to the formation of ruling class power makes it a very difficult target.

the shareholder revolution

For a long while, shareholder ownership was more notional than active. After the 1929 crash, Wall Street sort of receded into the background, giving us the Golden Age of Galbraith’s managerial capitalism—when managers and technocrats ran corporations and shareholders were at most silent partners. But when economic performance faltered in the 1970s, when the Golden Age was replaced by Bronze Age of rising inflation and falling profits, Wall Street, meaning shareholders, finally asserted themselves. They unleashed what has been dubbed the shareholder revolution, demanding not only higher profits but a larger share of them. The first means by which they exercised this control was through the takeover and leveraged buyout movements of the 1980s. By loading up companies with debt, they forced managers to cut costs radically, and ship larger shares of the corporate surplus to outside investors rather than investing in the business or hiring workers. This cost-cutting mania helped drive the outsourcing movement.

The 1980s debt mania came to a bad end, as highly leveraged companies found themselves unable to cope with the early 1990s recession. So the shareholder revolution recast itself as a movement of activist pension funds, led by the California Public Employees Retirement System (CalPERS). The funds lobbied management, drew up hit lists of badly run companies, and generally pushed the idea that firms should be run for their shareholders. It had some successes. Compensation structures were rejiggered to emphasize stock over direct salaries; the idea was to get managers to think and act like shareholders, since they were materially that under the new regime.

But pension fund activism sort of petered out as the decade wore on. Managers still ran companies with the stock price in mind, but the limits to shareholder influence have come very clear since the financial crisis began. Managers have been paying themselves enormously while stock prices languished. If the stock price wasn’t cooperating, well, options could always be back-dated. The problem was especially acute in the financial sector: Bank of America, for example, bought Merrill Lynch because its former CEO, Ken Lewis, coveted the firm, and if the shareholders had any objections, he could just lie to them about how sick the brokerage firm was. It was as if the shareholder revolution hardly happened, at least in this sense. But all that money flowing from corporate treasuries into money managers’ pockets has quieted any discontent.

political coda

Wall Street demonstrated its immense political power during the financial crisis and its aftermath. Financiers may bellyache about increased regulation over the last couple of years, but the actual changes have been very minor. The major bill that changed the regulatory architecture, nicknamed Dodd–Frank, was weak tea to start with and is being watered down further as the detailed regulations required in the legislation are written.

So in return for hundreds of billions of dollars in public funds used to keep the financial system from going under, the banks will emerge from this crisis largely unscathed. One reason for this is Wall Street’s skill at lobbying, and its ability to spread huge amounts of cash around Washington. As Public Citizen documented, between 1998 and 2008, Wall Street spent $5 billion in campaign contributions and deployed 3,000 lobbyists across Capitol Hill to get its way. While $5 billion sounds like a lot, it was less than a third of the Goldman Sachs bonus pool for 2009, and spread out over a decade. Wall Street has a lot of money, and Congress can be bought on the cheap.

But, as I argued earlier, Wall Street also represents the commanding heights of the economy, the central mechanism by which ruling class economic power is formed and exercised. It’s only surprising to people who don’t understand this that Washington dances so faithfully to the bankers’ tunes.

In giving talks like this over the last few years, this is the point at which I’d moan about how in the midst of the worst sustained economic crisis in 80 years, the major political energy was coming from people with tea bags on their heads. It seemed that we needed—even in relatively mainstream terms—a serious rethink of the neoliberal economic model, and none was forthcoming. I would lament the lack of interest in doing anything serious about our economic situation, except embracing varying doses of austerity, which would only make things worse (see, for example, the periphery of Europe, which in this case includes Britain). I would worry about the inability even to admit, much less do anything, about the challenge of climate change. Then I’d move on to expressing a wish that I could detach myself from the consequences and find it all amusing, in the style of H.L. Mencken. But I couldn’t do that. Now that I’ve got a six-year-old who is growing up in this nuthouse, I’ve come to take it all more personally.

All this has changed dramatically in the last few months. Thanks to a small band of people who moved into a private park near Wall Street last September 17, political discourse and activism have taken the most hopeful turn that I can remember. I have my reservations about the ideological orientation of a lot of the Occupiers. And it’s hard to know whether this spirit will survive the winter—or the banalizing tendencies of presidential election campaigns. But I’m going to bracket that for now and admit to more than a shred of hope that things are turning in a seriously better direction. Finally.

Fresh audio product

Just posted to my radio archives (and, as always, the audio is often posted before the web page is updated, so for maximum timeliness, subscribe to the podcast—see headnote on archive for details):

January 28, 2012 Kevin Gray on South Carolina • Catherine Liu, author of American Idyll, on education, testing, anti-intellectualism, and the bogus politics of “anti-elitism”

January 21, 2012 Erin Siegal, author of Finding Fernanda, on adoption tragedies • David Cay Johnston on why Mitt is lightly taxed

Me in SoCal

I’m giving two talks in Southern California later this week (actually two versions of the same talk, “Reflections on the Current Disorder,” a title cribbed from William F. Buckley). Both are free and open to the public.

Wednesday, January 25, 3:30–5:00 PM

University of California–Riverside

CHASS INTS 1113Thursday, January 26, 4:30–6:00 PM

University of California–Irvine

1030 Humanities Gateway

I hope they won’t be too dull.

New audio product

Just posted to my radio archives:

January 14, 2012 Lane Kenworthy, author of this paper (PDF), on just how much economic growth trickles down, and why (spoiler: U.S. does very badly) • Enrique Diaz-Alvarez, chief strategist for Ebury Partners, on the eurocrisis, with an emphasis on Spain

A chat with Larry Summers (from 2000)

This is from Left Business Observer #94, May 2000.

chatting with Larry

LBO’s editor was lucky enough to run into Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers at a party in Washington on April 15, and got to overhear some of his thoughts on the weekend’s events and even ask a few questions.

Early in the evening, surrounded by what appeared to be some loyal scribes, Summers enthused about how “proactive” the DC cops were, having arrested some 600 demonstrators, “including many of the leaders.” Summers is evidently unaware that the Direct Action Network types who constituted the hardcore of the demonstrators are resolutely anti-hierchical and don’t have leaders in the sense that he understands them. Later, as Summers was leaving, I got to ask him a few questions. Asked what he made of the crowds filling the streets, Summers, evidently forgetting his earlier enthusiasm for mass preemptive arrests, said he “admired their moral energy,” but thought their prescriptions would only make the poor poorer. When it was pointed out to him that the gap between the world’s rich and poor had been widening under the policies he and his like-minded predecessors have pursued, he claimed that this has been a great time of progress for the world’s poor. Finally, when asked if Africa was still vastly underpolluted — a reference to his infamous 1991 memo, written when he was chief economist of the World Bank, suggesting that it was — he seemed a bit startled, conceded that it was a “fair if unfriendly question,” and said that it’s been well established that he (or rather Lant Pritchett, the author of the words that went out under Summers’ name) was merely being sarcastic and not serious.

Looking at the state of the world’s poorest continent, it seems that truths are told in moments of “sarcasm” that elude the powerful in their more serious capacities.

PS: As this issue goes to press, we just learned that on Summers’ orders, former World Bank chief economist Joseph Stiglitz (LBO #93) had his consulting contract cancelled. A critical article in The New Republic, in which, among other things, Stiglitz dis’d the quality of the IMF’s staff economists, was apparently the last straw.

Larry Summers, future World Bank president?, on how Africa is vastly underpolluted

So Obama’s going to nominate Larry Summers to be president of the World Bank. Recall this passage from 1991 memo, actually written by Lant Pritchett but signed by Summers when he was the Bank’s chief economist, on how “Africa is vastly under-polluted.” The last paragraph is important, and should not be overlooked in fighting these mofos.

3. “Dirty” industries

Just between you and me, shouldn’t the World Bank be encouraging more migration of the dirty industries to the LDCs [less-developed countries]? I can think of three reasons:

1) The measurement of the costs of health impairing pollution depends on the foregone earnings from increased morbidity and mortality. From this point of view a given amount of health impairing pollution should be done in the country with the lowest cost, which will be the country with the lowest wages. I think the economic logic behind dumping a load of toxic waste in the lowest wage country is impeccable and we should face up to that.

2) The costs of pollution are likely to be non-linear as the initial increments of pollution probably have very low cost. I’ve always thought that underpopulated countries in Africa are vastly under-polluted, their air quality is probably vastly inefficiently low compared to Los Angeles or Mexico City. Only the lamentable facts that so much pollution is generated by non-tradable industries (transport, electrical generation) and that the unit transport costs of solid waste are so high prevent world welfare enhancing trade in air pollution and waste.

3) The demand for a clean environment for aesthetic and health reasons is likely to have very high income elasticity. The concern over an agent that causes a one in a million change in the odds of prostrate [sic] cancer is obviously going to be much higher in a country where people survive to got prostrate cancer than in a country where under 5 mortality is 200 per thousand. Also, much of the concern over industrial atmospheric discharge is about visibility impairing particulates. These discharges may have very little direct health impact. Clearly trade in goods that embody aesthetic pollution concerns could be welfare enhancing. While production is mobile the consumption of pretty air is a non-tradable.

The problem with the arguments against all of these proposals for more pollution in LDCs (intrinsic rights to certain goods, moral reasons, social concerns, lack of adequate markets, etc.) could be turned around and used more or less effectively against every Bank proposal for liberalization.