Fitch lecture: 13th annual edition, with Robin D.G. Kelley

on Monday, March 18, at LaGuardia Community College in Long Island City, Queens. Kelley, a distinguished professor of history at UCLA, is calling his talk “From the Waterfront to the Sea: Working Class Democracy and the Question of Palestine.” I’ll be doing the intro.

More info here.

on Monday, March 18, at LaGuardia Community College in Long Island City, Queens. Kelley, a distinguished professor of history at UCLA, is calling his talk “From the Waterfront to the Sea: Working Class Democracy and the Question of Palestine.” I’ll be doing the intro.

More info here.

Fresh audio product: the bankers’ club and how to bust it, the problem with immediacy

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

February 15, 2024 Gerald Epstein, author of Busting the Bankers’ Club, on the finance racket and how to transform it • Anna Kornbluh, author of Immediacy, on our sped-up, unmediated cultural eternal present

Vibecession over

Though I’m certainly not the first to make this observation, it looks like the “vibecession” is over. The term was coined in June 2022 by multimedia economic analyst Kyla Scanlon (drawing on Keynes but also the poetry of Charles Bukowski), who defined it as “a disconnect between consumer sentiment and economic data. So basically, the economy is doing fine, but people are absolutely not feeling fine.” By recent measures, people are starting to feel somewhat finer, if not bounce-off-the-walls fine.

The Conference Board’s consumer confidence index rose 6.8 points in January to its highest level since December 2021. The index is the summary of a monthly survey the organization has conducted since 1967 that asks people questions about the state of the economy, the job market, and their personal finances, both in the present and their expectations for the future. Separate indexes for the present and expectations questions are computed, and then averaged into a composite. The history is graphed below.

January’s rise in the composite was led by its “present conditions” component, up 14.1 points to the highest level since March 2020. Driving the rise were improving evaluations of the job market, as the gap between those reporting “job plentiful” and those reporting them “hard to get” expanded 8.4 points to 35.7 in favor of plentiful—very high by historical standards (higher than 94% of all the months in its 57-year history). Expectations, alas, are more muted.

Gallup agrees on the improvement, though not on its degree. The present component of their economic confidence index rose to its highest level since November 2021 in January, but it’s still negative on balance. (It’s computed as the difference between the share of respondents calling the economy excellent or good and the share calling it poor. Just 5% of respondents in the January survey called it “excellent,” and 22% “good.” Far more, 45%, called it poor. for a net of -18%.) The expectations side, while also net negative, is at its least negative level since September 2021. There’s no graph of these because there are often long stretches between surveys and such a graph would be ugly.

And another: the University of Michigan’s consumer sentiment measure (graph below) was up 9.1 from December on its preliminary January reading, reaching its highest level since July 2021. It was also led by evaluations of the present, though expectations were somewhat loftier than the Conference Board’s counterpart. Sentiment had really been plumbing the depths: in June 2022, the month Scanlon coined the term, the index hit 50.0, its all-time low in over seven decades of history—below the depths of the Great Recession. Not coincidentally, it was also the month of peak inflation.* The sentiment index’s full-year 2023 average was 8 points below the long-term recession average. January’s improved reading was nonetheless still almost 10 points below the average of all business cycle expansions since 1952.

inflation down

Much of this improvement in outlook is the result of the decline in inflation, from 8.9% in June 2022 to 3.3% in December 2023, a fall of almost two-thirds. We hadn’t seen 8.9% in 42 years. December’s 3.3% is above the 1990–2019 average of 2.5%, but not profoundly so.

Along with the decline in actual inflation has come a decline in expected inflation. I’ve long thought that instruments that measure “expectations” are mostly about the present and recent past and have little or no prognostic content. (As the graph below shows, expectations for price increases over the next twelve months generally track the experience of the previous twelve.) Instead, expectations can be read as a measure of a subjective state—in this case, how established inflation feels as a part of life, what the current norm is.

By this measure, inflation’s psychological grasp looks to be slipping. As the graph shows, expectations for the next year have come down along with actual inflation, from over 5% in mid-2022 to 2.9% in January.

That matters a lot—people hate inflation! Liberals and leftists tend to dismiss inflation as a concern of anal-retentive reactionaries, but that badly misreads popular opinion. I made this argument at some length in my long Jacobin article on inflation, but here’s another piece of evidence to add to that: Scanlon cites a Morning Consult poll that found 63% of consumers prefer prices going down to their income going up. Economists natter on about “real” (inflation-adjusted) income, but they may not be giving enough weight to the price part.

partisan coda

Speaking of the Michigan sentiment numbers, the improvement in outlook over the last couple of months crosses partisan lines, but the gap between Democrats and Republicans widened. Partisan gaps have long been visible in the survey, but they were much less dramatic than they’ve been since January 21, 2017. During the Obama years, Dems’ consumer sentiment ratings were about 18 points higher than Republicans’. During the Trump years, the gap more than doubled to 39 points, though it switched parties to favor Republicans. For first three of the Biden years, the parties flipped again, as Dems’ evaluations exceeded Reps’ by 35 points, even though nothing had changed by conventional economic measures. Independents, not surprisingly, split these differences.

Between November 2023 and January 2024, both parties saw strong increases in their evaluations of the economy, but Dems, up 17 points, were more enthusiastic than Reps, up just 15. So the gap widened to 44 points.

Much of the lift to the overall sentiment measure for Republicans—over three-quarters of it—came from expectations, not evaluations of the present; perhaps they’re hopeful about November’s election results.

Otherwise, the end of the vibecession might be good news for the hapless warmonger Biden, who needs some.

* In June 2022, when the sentiment measure was at its record low of 50.0, the unemployment rate was 3.6%. It was also the high for the recent inflation surge: 8.6%. In October 2009, when the unemployment rate was 10.0%, the worst reading of the Great Recession, the sentiment index was 70.6. But there was literally no inflation: for the year ending October 2009, the consumer price index was down 0.2%.

Fresh audio product: why did SA bring case against Israel, organizing amidst sprawl, the widening war in the Middle East

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

February 1, 2024 Sean Jacobs explores why South Africa brought the genocide case against Israel • Eric Blanc (Substack post here) on organizing in a scattered and atomized society • Hassan El-Tayyab on the widening war in the Middle East

Fresh audio product: Houthis, Hezbollah

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

January 25, 2024 Shireen Al-Adeimi of Michigan State and the Quincy Institute, on the Houthis • political scientist Aurélie Daher with another view of Hezbollah

Unions had a flat 2023

Despite an apparent upsurge in labor militancy, unions made no gains in their share of the workforce last year. According to newly released figures from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, in 2023, 10.1% of the workforce belonged to a union, unchanged from the previous year and down 0.2 from 2019. There was a spike in union density in 2020, as more nonunion workers left the workforce than their organized counterparts in the early covid days, but that was quickly reversed in 2021.

Since 1965, union density has risen only four times from one year to the next; it’s fallen in 45. Although long-term comparisons are dangerous—definitions, coverage, and methods can change radically over time—it looks like the private sector union share today is lower than it was in 1900.

The public sector, once the brighter spot in the union picture, has lately been leading the way down. Since 2011, the decline in public sector density is four times that of the private sector’s. The right’s war on public sector unions has taken a serious toll. The grim story is graphed below.

pay

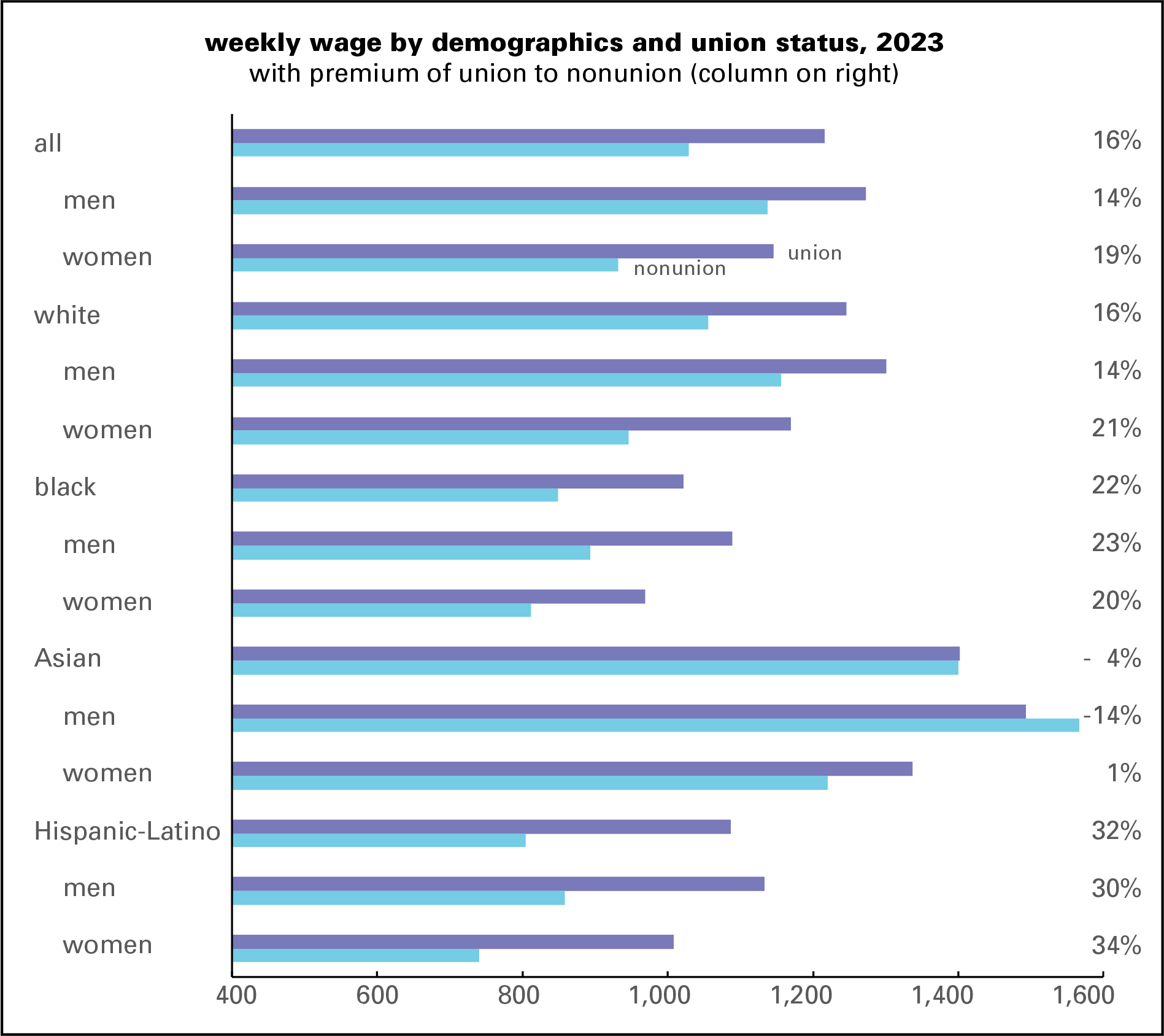

Much of the material difficulties experience by the working class over the last few decades can be traced the shrinkage of unions—lower wages, stingier benefits, less job security. Pay is the most obvious measure. As the graph below shows, union members have weekly paychecks 16% larger than nonunion workers. The union premium is larger for groups that are the victims of discrimination—women and non-whites. Women enjoy a 19% union premium overall; black women, 20%; and Hispanic (as the government calls them) women, 32%. Nonwhite men also enjoy bigger union premiums than white men. The only exception is workers of Asian origin; it’s likely that the high share employed in tech (a sector where unions are rare) is responsible.

geography

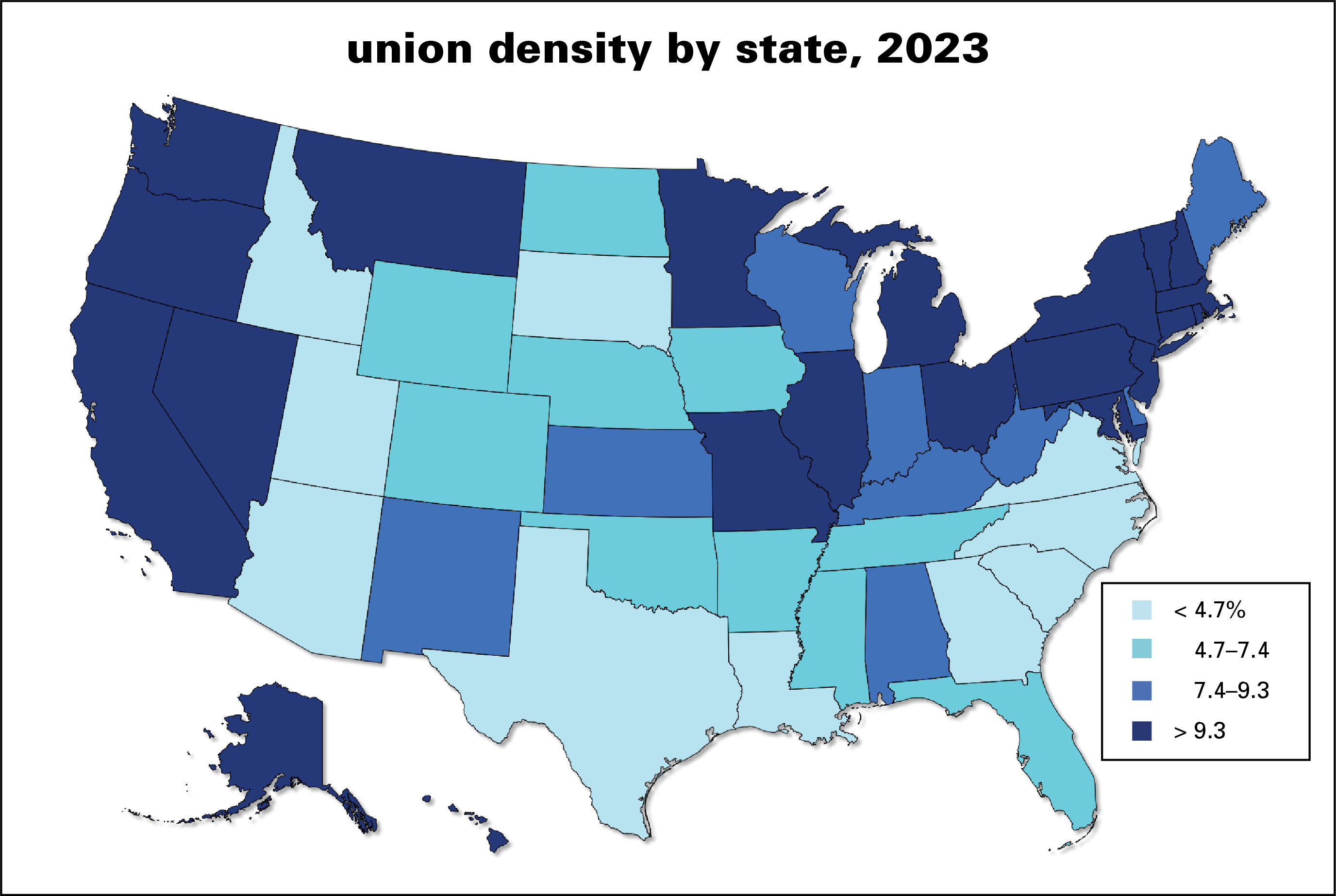

Union density varies widely by state, from Hawaii’s 24.1% to South Carolina’s 2.3%. The map below shows some clear regional patterns, with the Northeast, upper Midwest, and West showing the highest densities and the South the lowest. The ten states that gave Donald Trump the highest share of their 2020 vote have an average density of 6.3%; the ten lowest, 15.2%. The states of the old Confederacy have an average density of 4.8%; the rest, 10.7%. Curiously, the state with the lowest density, South Carolina, had the largest share of its population enslaved before the Civil War.

shrinking premium

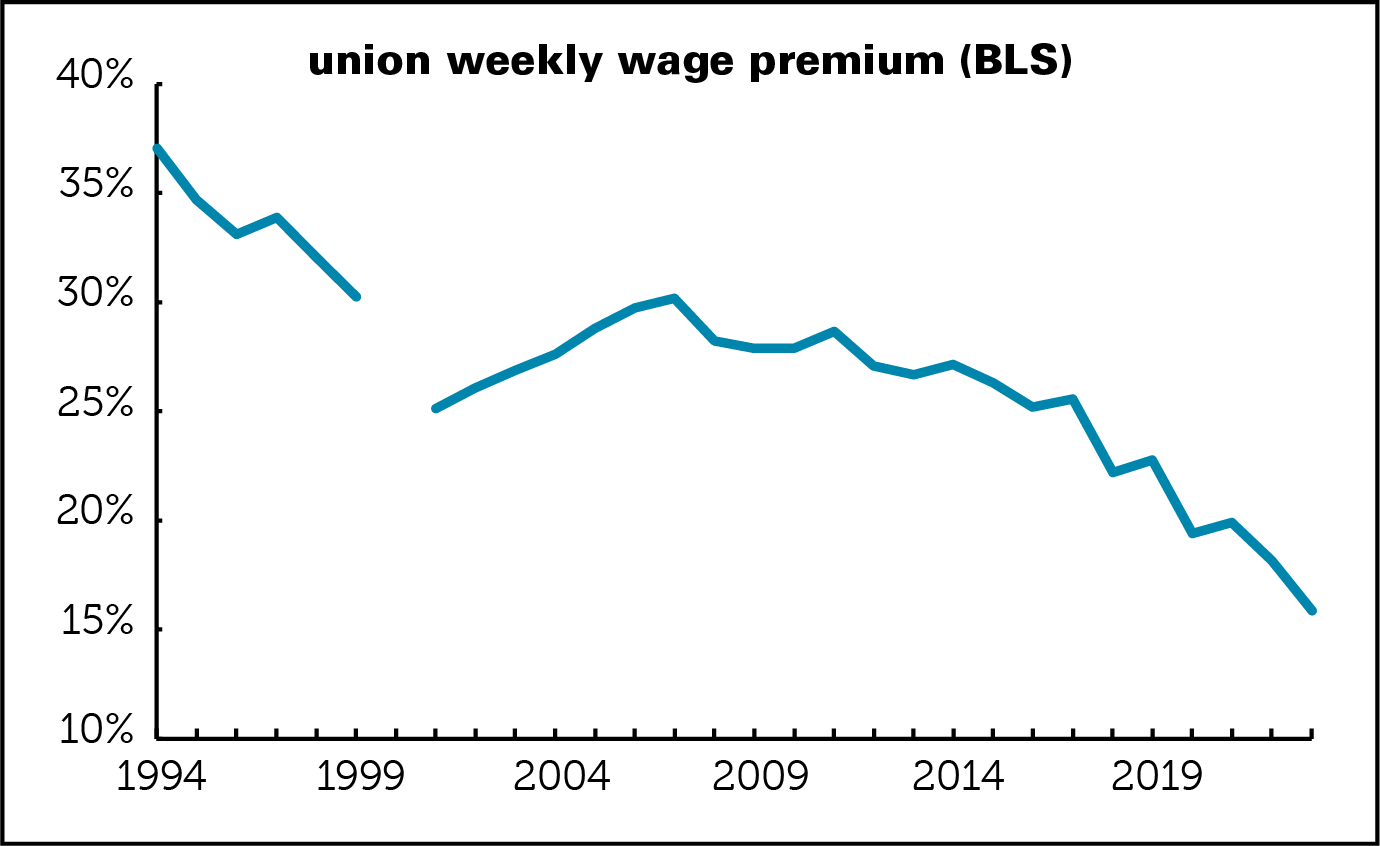

That union premium has been shrinking over time, as unions have weakened more generally. Here’s a history showing the ratio of the weekly pay of all union workers to nonunion since 1994. (Figures for 2000 are unavailable. There’s no simple source of the historical data—you have to enter it by hand from annual releases.) The premium has declined steadily for three decades, from 37% in 1994 to 16% in 2023. While 16% isn’t nothing, the premium is less than half what it was back in the early Clinton era.

This graph is based on weekly wages, which are a half-decent proxy for workers’ “normal” wage (though people do cycle in and out of work, and sometimes hours can be hard to come by). But since workweeks can vary by time, industry, region, and worker characteristics (as economists say) it’s also worth looking at hourly pay.

That too is in decline, as the chart below (from UnionStats data) shows. The “unadjusted” line has fallen from a high of 31% in 1977 to 6% in 2023, a decline of 80%. But the unadjusted average, like the BLS averages above, mixes together workers of varying demographics (like age, sex, region, and race) from a variety of industrial sectors, with wide differences in pay and unionization rates. As those mixes change over time, the averages change, which obscures the pure union effect.

The line marked “adjusted” is an attempt to control for those compositional changes and compare workers who are similar except for their union status. That too has declined, though not as much—from 21% in 1977 to 10% last year, or just over 50%. That’s a lot but it’s less than the 80% decline in the unadjusted numbers.

coda

Of course, any premium >0% will inspire bosses to hate unions and want to destroy them—and not just for the higher pay. Unions are a constraint on boss behavior; they can force them to be less racist, less abusive, and less able to fire. But clearly they’ve lost a lot of their bite over time.

As I say every time I do these reviews:

There are a lot of things wrong with American unions. Most organize poorly, if at all. Politically they function mainly as ATMs and free labor pools for the Democratic party without getting much in return. But there’s no way to end the 40-year war on the US working class without getting union membership up….

It’s still true, though I should probably add a few years to that “40” timespan.

fresh audio product: electronic monitoring, Hezbollah, an introduction

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

January 18, 2024 Wanda Bertram of the Prison Policy Initiative on electronic monitoring (the ankle bracelet kind) • Joseph Daher, author of Hezbollah: The Political Economy of the Party of God, on that demonized organization

Fresh audio product: perils of striking Trump from the ballot, a good year for labor

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

January 4, 2024 Samuel Moyn, law prof and historian, on the political and legal dubiousness of excluding Trump from the presidential ballot (article here) • labor journalist Alex Press on the year in labor (articles on that topic here and here)

Fresh audio product: what’s driving Israel’s war on Gaza, what’s with philanthropy

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

December 14, 2023 Joel Schalit, editor of The Battleground, on what it is in Israeli politics and society that’s behind the carnage in Gaza • Amy Schiller, author of The Price of Humanity, on what’s wrong with philanthropy and how to fix it

Fresh audio product: Gaza in a global context, Israeli spying on US campuses, fascism: this year’s model

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

December 7, 2023 Trita Parsi on the global context of the Gaza war • James Bamford, author of this article, on how Israel spies on US campuses • Alberto Toscano, author of Late Fascism, on the latest iteration of the rough beast

The private equity racket

This is the edited version of a talk I gave at New York City political education event on private equity, December 2, 2023. My fellow panelists were Kim Phillips-Fein and Holden Taylor. Video is here.

You’ve always got to start somewhere, so I think I’ll start as the 19th century was turning into the 20th. As the scale and technical complexity of production increased, the previously existing world of businesses that were run either as sole proprietorships or small partnerships were inadequate to the task. They gave way to what would become the large, professionally managed corporation, many of which were assembled from smaller pieces by the likes of J.P. Morgan. Morgan hated competition as a destructive force, and while his preference for private monopolies controlled by the likes of him is not our social ideal, neither should we romanticize the old world of small competitive firms. In his book on the Morgans (which I reviewed long ago, here), Vincent Carosso quotes an unnamed socialist observing on JP’s death: “We grieve that he could not live longer, to further organize the productive forces of the world, because he proved in practice what we hold in theory, that competition is not essential to trade and development.” Competition has never been a socialist virtue.

These new large firms were marked by what later would be called the separation of ownership from control. The official owners were outside investors, stockholders, who could sell those shares to other investors if they liked but they had little influence over corporate policy. That was set by an increasingly professionalized caste of formally trained managers. The first US business school, Wharton, was founded in 1881, and over the next couple of decades others sprang to life, including Harvard’s in 1908. The professionals’ victory wasn’t complete; financial operators still played a big role in what we call today corporate governance—how firms are run and for whom.

But with the crash of 1929, the financial operators who’d manipulated and cheated their way through the Roaring Twenties, were beaten back, their freedom to maneuver greatly hobbled first by shame (and a few prison sentences) and then by the regulatory reforms of the 1930s. Legal scholars and economists began reflecting on what it meant that it meant that shareholders were now mostly millions of dispersed individuals—concentrated among the affluent, of course, but incapable of communicating with each other about the companies they owned—and managers were largely free to run their firms. Sure, dissatisfied shareholders could sell their stock, but they had no leverage over their hired managerial hands.

That began to change in the 1970s, when, at the same time, institutional investors like pension funds replaced individuals as stockholders and corporate performance deteriorated with the stagflation of the 1970s. In the early post-World War II decades, profits, dividends, and share prices rose more or less reliably; that was no longer true. The major financial markets, stocks and bonds, had one of their most miserable decades in history. And these institutional stock owners were roused to action, led by the buyout artists who would become the commanders of the Shareholder Revolution. Their organizing revolutionary doctrine was that getting profits up, and therefore stock prices, was the only point of business enterprise; all notions of responsibility and stakeholdership should be junked in favor of pure profit maximization.

the Shareholder Revolution

The roots of modern private equity were in the early post-World War II years, but things didn’t really get rolling for a few more decades. In the lead were the trio Jerome Kohlberg, Henry Kravis, and George Roberts (Henry’s cousin), who were working at the investment firm Bear Stearns in the mid-1960s. They started small, doing debt-financed buyouts of family-owned companies in the 1960s and 1970s. The trio founded their own eponymous firm, Kohlberg Kravis Roberts, in 1976; many others soon followed. KKR would become one of the giants of PE. Kohlberg died in 2015; Kravis and Roberts are no longer running the show but still serve as co-executive chairs.

At first the buyout deals engineered by KKR and its early colleagues were small and financially sensible, but as the Roaring Eighties really got roaring, the deals and the loans that financed them got bigger. The archetypal deal of the decade was called a leveraged buyout, or LBO (which inspired the name for the newsletter I ran from 1986 to 2013). LBOs involved borrowing lots of money to take over companies, cutting costs sharply, and then offloading the property a few years later by going public again or selling it to someone else, like another buyout boutique or to the public by a stock offering. The LBO movement’s principal mode of funding was junk bonds, high-interest rate debt most famously associated with the rogue brokerage Drexel Burnham Lambert, run from an X-shaped desk in Beverly Hills by Michael Milken, who later went to jail for securities fraud. Milken assembled a coterie of buyout artists armed with money he could raise in an instant from his investors’ circle and for a decade they wilded their way across the corporate landscape.

The decade saw over 2,000 LBOs worth over $250 billion. Many of them were hostile takeovers, meaning unwelcome by management. It was quite an episode of intraclass warfare, as stodgy old-line CEOs were attacked by takeover artists and displaced. Along with KKR and the gang, raiders like Boone Pickens and Carl Icahn became household names, at least in households that got the Wall Street Journal home delivered.

There was a theory behind all the turmoil. Its chief proponent was Michael Jensen, a professor at the Harvard Business School, who wrote a series of papers arguing that corporate management was wasting money that should instead be going to shareholders, who in Jensen’s worldview were paramount for undisclosed reasons, on things like perks and employment. The ideal, he argued, was a world in which “alternative managerial teams compete for the rights to manage corporate resources.” Corporations should not be stable institutions, but instead exist in a state of capitalist permanent revolution. Managers, Jensen argued, should be paid principally in stock, so they’d think and act like shareholders, instead of being paid fixed salaries. And, he further counseled, loading up firms with debt would serve as an excellent disciplinary device: having to cover the interest bill would force the closure or sale of weaker divisions and cost-cutting in the survivors.

The mania is usually said to have kicked off with the 1982 buyout of Gibson Greeting Cards, a deal lead by former Treasury Secretary and political reactionary William Simon. The investors kicked in about a million dollars of a total purchase price of $80 million. Less than a year and a half later, Gibson went public by floating $290 million in stock. Simon personally made $60 million. This success inspired many imitations. The mania peaked with KKR’s 1989 buyout of RJR Nabisco, universally seen as a debacle. The company was sold off piece by piece and ceased to exist a decade later; 2,000 workers lost their jobs.

RJR’s fall was the emblematic end to the Roaring Eighties. Hundreds of firms found themselves unable to service their debts. Bankruptcies replaced buyouts in the headlines and Drexel got put out of business by the government. But the turmoil had a lasting effect on class relations. The challenge of servicing large debts meant firms had to hammer away at costs, and for most, their major cost is labor. Wage-cutting and mass layoffs hammered working class living standards and self-confidence. For the dwindling number of workers with unions, concessions became the norm, and workers were often grateful to have a job at all. That deferential reflex persisted for decades and may only now be lifting.

PE goes straight

At the top, the Shareholder Revolution transformed executive pay: Jensen’s dream of having CEOs paid in stock was realized, and the antagonism that characterized financial market–executive relations in the 1980s was resolved, largely on finance’s terms. PE began reviving from the early 1990s hangover, newly respectable, no longer associated with unsavory takeover artists and felonious investment bankers, and CEOs, their hearts with the stock price, often welcomed takeover offers.

PE entered another winter in the early 2000s, after the collapse of the late 1990s tech bubble, only to rise again. Deals got huge once again, and big PE firms like Blackstone, TPG, and Carlyle were all over them. An innovation in the period was PE firms going public by selling stock, notably Blackstone in early 2007. (At the time, I wrote in The Nation that the timing suggested that the great bubble of that decade was about to pop—those Blackstone guys are clever; the great financial crisis was underway just months later.) Blackstone was careful to keep all the voting rights for itself and took first cut of profits. A number of other PE firms followed; it was like free money.

The early 1990s were time of relative calm, financially. The economy was in what some on Wall Street called a “contained depression,” which they thought was a good thing since it meant the Fed would keep interest rates low and credit easy. That marked the onset of a change in the politics of money and credit. The hard money Wall Street of the late 1970s and early 1980s, when Fed chair Paul Volcker drove up interest rates towards 20% to break inflation was giving way to a Wall Street that loved a generous Fed, since it raised asset values and made it easy to borrow.

By the middle of the decade, the old LBO movement was reborn as private equity. PE stumbled some during the Great Recession following the 2008 financial crisis, and then boomed, as the Fed (led by PE alum—Carlyle specifically—Jay Powell) printed money in large quantities, stumbled briefly during the covid spill, and then soared along with everything from bitcoin to Nikes. Higher rates and tighter financial conditions have slowed it down over the last year or two, but these guys do have a habit of shrugging off adversity.

PE’s world

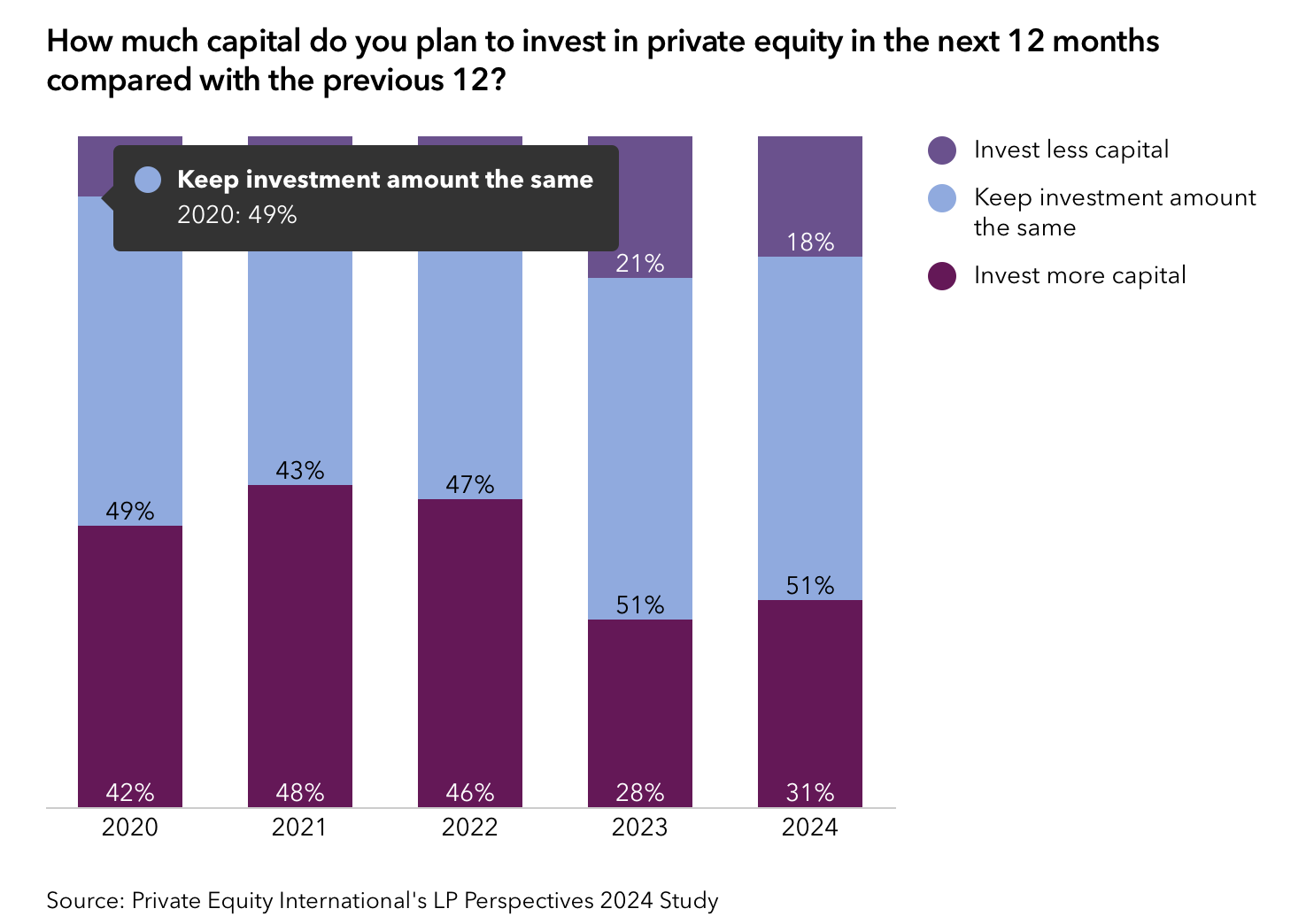

Today, a typical private equity firm is managed by a smallish staff that uses money contributed by institutional investors like pension funds and university endowments to buy up whole companies. They’re a worldwide phenomenon, but their spiritual home is in the US, as is the bulk of their money. Typically, they run the firms they own for a few years, cutting costs and rearranging their components, and then sell them, either to the public in a stock offering or to another private equity firm. Also typically, PE operators load the firms they own up with debt to pay themselves fees and dividends. These are not meant to be long-term relationships. The idea is to contribute as little as possible, extract as much as possible, and “exit” (the term of art) a few years later.

And those fees! The typical structure is 2 and 20, short for 2% of assets under management plus 20% of the profits. Since that could never be enough, they add to the take with whatever they can extract from their portfolio companies, as they are called. Top executives’ pay is very tax-favored; attempts to remove that break have always collapsed. When Obama suggested repealing it in 2010, Blackstone head Steve Schwarzman likened the suggestion to Hitler’s invasion of Poland in 1939.

PE has become a major presence in the US economic landscape. According to the industry’s trade association, the American Investment Council, 12 million people work at 32,000 PE-owned companies, about 8% of the total workforce.

PE’s appeal for outside investors is that the vehicles supposedly offer higher returns than the public stock markets, but the evidence for that proposition is shaky. In fact, it’s hard to argue, when taking risk into account, that the high fees produce better returns than what’s offered by a Vanguard index fund with fees close to 0.

Some of the big names in the field include Blackstone, The Carlyle Group (DC-based, unusually, and with deep associations with the federal government and the national security state in particular), TPG Inc. Silver Lake, and Bain (what made Mitt Romney rich). Let’s take a quick look at Blackstone.

Blackstone, founded in 1985 by Pete Peterson (now dead) and Steve Schwarzman (now #34 on the Bloomberg Billionaires List, worth, if you can call it that, $38 billion) has been the biggest player in private equity for most recent years. It sometimes loses the top spot to KKR, as it did last year, but it’s back on top now. (Along with PE, they also have real estate and hedge fund divisions.) It has a trillion dollars under management, about a third of it in the private equity division. Just 250 people work in the PE segment, which works out to $1.2 billion of capital to allocate per employee. (KKR has about 2,000 employees.) New investments over the year ending in June were about $29 billion, and proceeds from sales of companies came to $24 billion, numbers taken together that suggest a lot of turnover. For top management, the game is very lucrative; last year, Schwarzman’s pay was one and a quarter billion.

Among the 200 companies it owns, who all together have half a million employees: Emerson Climate Technologies, Ancestry.com, Bumble, and Reese Witherspoon’s Hello Sunshine. A fuller list than appears on their web landing page would include some recognizable names, but they’re mostly not headliners. A trip through KKR’s holdings leaves a similar impression.

Over the last couple of decades, PE has left a pile of corporate corpses in its wake, with some of its highest-profile victims in retail. Many shopping mall stalwarts who’ve disappeared over the last decade or two—most notoriously, Toys R Us— were driven under by PE’s depredations. You could argue that the decline of brick-and-mortar retail meant these stores were doomed anyway, but it’s not clear why vulture investors should drink their last drops of blood rather than the workers. PE firms are very active in the nursing home sector, which were already dominated by thin staffing and low wages. PE means thinner and lower. Dentistry chains are another popular target; there, they’re encouraging pointless root canals to boost the cash flow.

scattered speculations

Finally, a couple of sociological notes on the growth of PE.

• Liza Featherstone and I did a piece for In These Times back in 2018 showing how deeply invested public pension funds are in private equity (and many unions are happy to play along—and not only in the US: the Ontario teachers’ fund is a notorious partner of PE firms). They’re in search of higher returns, but as I said earlier, management fees eat up much of the notional gains. The PE strategy is deeply anti-worker; cutting labor costs is central to any debt-extraction strategy. Interest and fees must be paid.

Pension fund investment in PE has a long history. Back in the early 1980s, when KKR was first getting started and was desperate to legitimate itself with big institutional investors, it got a seal of approval from the Oregon state pension board. Other funds soon followed. As KKR’s George Roberts told the Oregon pension board in 2013, “You all are our longest standing partner. We always start with you.” Given that these funds are managed in the name of workers, this is class treason.

• PE a fitting symbol for a bourgeoisie that has lost any sense of mission. In the last Gilded Age, rampaging capitalists like Carnegie built libraries and like Rockefeller build cathedrals and universities. Now, our shallow and ludicrous titans use their riches to shoot themselves into space. They seem not to think they need to legitimate themselves; their money is enough.

PE’s strategy of asset stripping is an extreme example, but rates of net investment—net that is net of depreciation—which is accounting’s way to measuring decay—in both the private and public sectors are very low. Contrary to the worrywarts, profit rates have long recovered from their 1970s lows, and the capitalist class is rolling in money. Its financial branch, however, is claiming more of the corporate surplus for itself, thanks in no small part to the practice of corporations buying up their own stock to boost its price, one of the durable legacies of the Shareholder Revolution.

• The rightward move of the Republican party has been greatly lubricated by the increasing wealth and political engagement of these private actors, the PE titans like Schwarzman and the Charles Koch and his circle, which is heavy with the heads of private corporations like Koch himself. Schwarzman was an economic adviser to Trump, whatever that means, and was one of the last respectable businesspeople to break with him. Kravis, by the way, is a more establishment-style Republican—but he was not above giving a million to Trump’s inaugural festivities.

Trump’s business style was not unlike that of PE. He ran a real estate firm with a small staff and no outside shareholders. Like a private equity guy, Trump loaded up his casinos with debt and pocketed much of the proceeds of the loans. That’s what happened with his Atlantic City casinos; it’s pretty hard to lose money in that business but Trump’s all went bankrupt. He did fine, though. What unites these guys—PE mavens, the Koch circle—is that they don’t want to answer to anyone or anything other than their own money, neither shareholders nor the government.

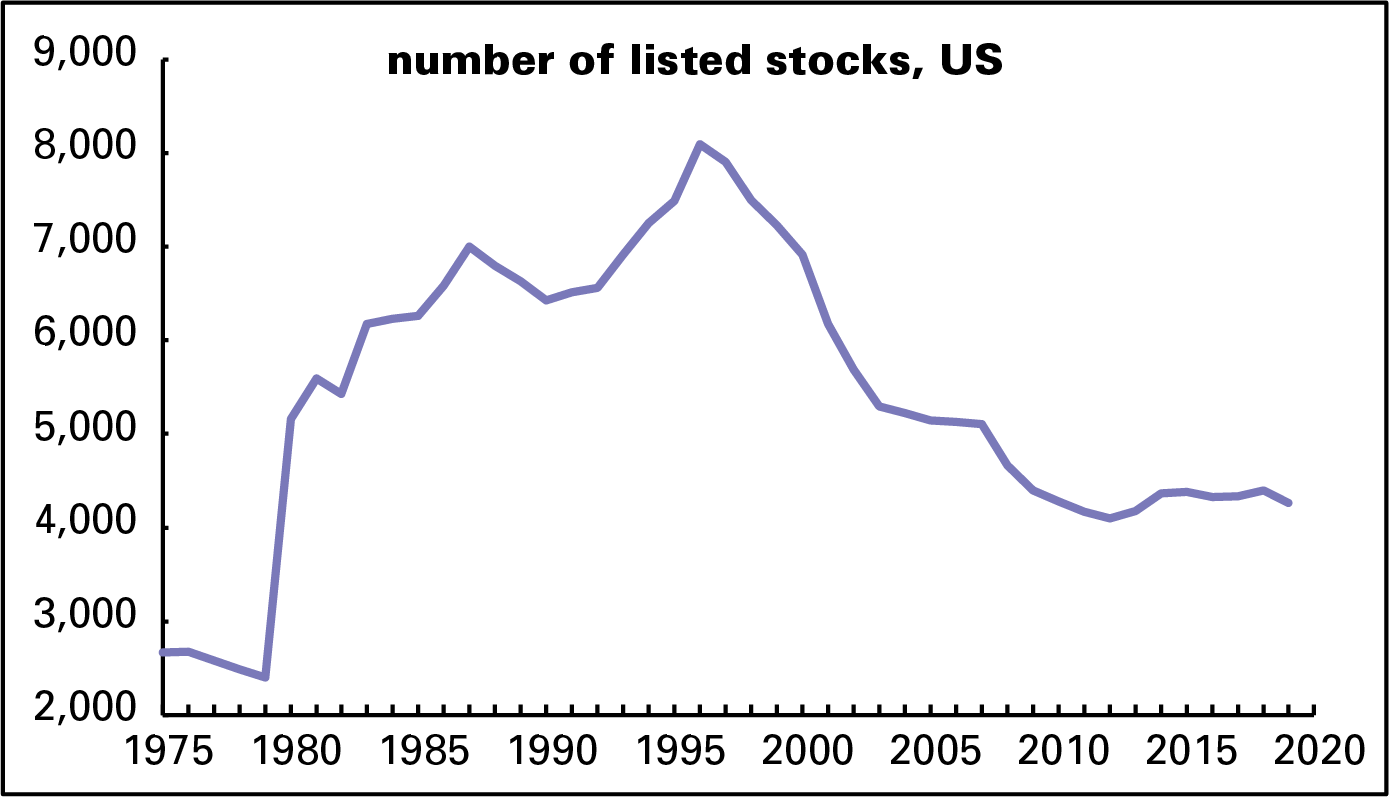

• This is all of great political importance, but there’s also something of theoretical interest here too. Over the last few decades, we’ve seen a sharp decline in the number of listed companies (those whose stock trades on public markets) alongside the rise of the fully private firm. (Graph above.) Marx described the emergence of the joint-stock corporation, with its separation of ownership and management, as “the abolition of the capitalist mode of production within the capitalist mode of production itself, and hence a self-abolishing contradiction.”

The self-abolition now looks to be of the public corporate form. The modest gains in transparency and accountability that have come with the public corporation and its disclosure requirements are being junked in favor of opacity and unchecked boss power. I suppose this is appropriate to a period of reaction, but it doesn’t sound like a good development.

Fresh audio product: political economy—the feline angle; understanding capitalism to smash it

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

November 30, 2023 Leigh Claire La Berge, author of Marx for Cats, on political economy and the human–feline relationship • Michael Zweig, author of Class, Race, and Gender, on understanding capitalism in order to transform it

Posted on February 8, 2024 by Doug Henwood

fresh audio product: exhausted humanity faces climate crisis, recessions raise lifespans

Just added to my radio archive (click on date for link):

February 8, 2024 Ajay Singh Chaudhary talks about his new book, The Exhausted of the Earth: Politics in a Burning World • Matt Notowidigdo, co-author of this paper, on how recessions increase life expectancy

Share this: