Ezra Klein thinks constructively about Walmart

Neoliberal über-dweeb Ezra Klein just unleashed one of those “balanced” efforts on the controversies of the day that are so characteristic of his species: “Has Wal-Mart been good or bad?” The conclusion, it might not surprise you to learn: it’s “a complicated question to frame and a devilishly tough one to answer.”

Drawing on—I’m not kidding—Reason editor “Peter Suderman’s 17-part Twitter defense of Wal-Mart,” Klein asserts that Walmart’s low prices are a gift to low-income consumers. (They’ve dropped the hyphen/star, folks; here’s the official timeline.) The Bentonville behemoth’s wages may be low, but not “when compared with the prevailing wages in the retail sector.” Walmart’s influence in setting wages is not a topic that they consider. Nor does either our neoliberal or our libertarian actually look at the history of retail wages, because it would be rather inconvenient for their argument.

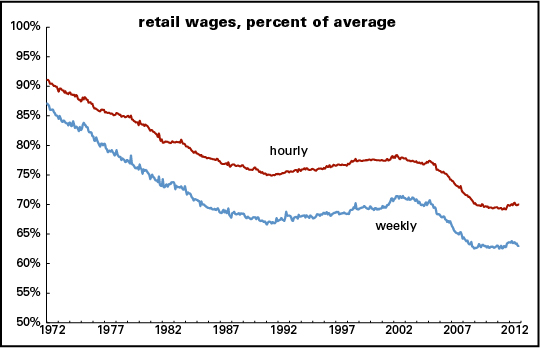

Over the last 40 years, as the real value of the hourly wage has fallen—down 9.3% since the January 1973 peak—the real retail wage has fallen three times as hard, 28.7%. The decline in weekly wages is even harsher, as workweeks have gotten shorter: down 17.2% in inflation-adjusted terms for all workers, but 38.3%, more than twice as much, for retail workers.

Or, looked at another way, the average retail hourly wage was 91% of that for all workers in 1972 (when the BLS’s retail wage stats begin) to 70% in October 2012. The decline in the weekly ratio was even steeper—from 87% of the average in 1972 to 63% in October. Here’s a graph of that history.

So clearly there‘s been a massive squeeze not only on the hourly wage, but also the number of weekly hours, in retail. (The average workweek is down about 3 hours since 1972 overall—but about 5 in retail.) And who has been the dominant force in retail over these decades? Walmart, of course. Not only is it famous for everyday low wages—it’s also famous for never providing its workers with as many hours as they’d like to work in a week.

And, yeah, it’s nice that Walmart has been able to provide a working class facing at best stagnant wages with lots of cheap stuff, but Walmart has itself had no small effect on dragging average wages down. It’s not just that they’ve been an inspiring business model for the rest for corporate sector, impressed by the chain’s growth and profitability. That’s led to endless rounds of outsourcing and speedup. But also by lowering the cost of reproduction of the working class, to use the old language, they’ve made it easier for employers to keep a lid on wages. You might think of the minimum feasible wage as the one that would assure that most of the workforce could show up and labor day after day. By lowering the cost of the bare minimum, Walmart makes it a lot easier for all employers to pay less. That brings a smile to the faces of stockholders, of course, but no so much the average worker.

Back in 1985, Alex Cockburn, reflecting on a creepy editorial about what Augusto Pinochet’s proper approach to fighting “terrorism” a decade into his dictatorial term should be, remarked that it was an instance of “our old friend The Washington Post editorialist trying to think constructively again.” Clearly Ezra Klein is extending a noble tradition, even though the Post is a mere shadow of its once-grand self.

Responding to Mike Konczal’s response

Mike Konczal responds to my criticisms of the Rolling Jubilee by rejecting arguments I don’t really make, though he runs some of them through a caricature machine, and then brings up other “more important” worries that bear no small resemblance to mine.

I can’t even make sense of some of the things he says. For example, I’m not sure what this even means, much less how it fairly represents anything I said:

Doug Henwood, for instance, believes that this is generated by activists’ uncritical populism, or the anarchist anthrology of David Graeber’s Debt, or the reification of Bowles-Simpson’s debt talk. But this is putting the carriage before the horse.

Just what is the carriage, and what is the horse?

The first part of this passage is a tendentious summary of my argument that the StrikeDebt! people have inherited from American populism an obsession with money and finance as the root of all our economic problems, while not paying much attention to the things they connect to in the real world. So, debt is a symptom of crappy wages, unemployment, expensive health care and tuition, and a cheesy welfare state. It’s fine to organize and propagandize around debt as long as you use it as a point of entry into that larger conversation—but the StrikeDebt! people have so far done that more in passing, while fixating instead on a so-called “debt system.” They say they’ll move on to that, and I hope that’s true.

Apparently Konczal actually agrees with me, because he says about 600 words later that it would be wrong to focus too much on debt itself, and declares himself happy that “the Strike Debt coalition has worked to link its concerns back to larger ones of public health care, free education, and a more robust safety net. Weaving these concerns with broader ones is precisely the work that needs to be done.” I’m not sure that the coalition is actually doing those things very prominently; almost everyone who’s commented on the scheme is talking about the buybacks, and not those larger issues.

Moving along, I assume the reference to “anarchist anthrology” is a typo, and not an invocation of Anthrax’s 2005 greatest hits compilation. Konczal is ignoring what I think is an important point: that the movement is influenced by Graeber’s analysis of debt, an analysis that really has little to say about how debt works in capitalist societies. It fixates on debt as a transhistorical category, encouraging an obsession with it to the exclusion of other economic categories.

Konczal is also skeptical about my proselytizing for bankruptcy. I hardly think it’s a “universal solvent” (solution?) and never said it was. But it could be used by a lot more people than are using it now. And, while it can be expensive, as I pointed out in the bankruptcy chapter of the Debt Resistors’ manual—a passage that thankfully survived the collective editing process—you can get free representation by contacting your local bar association. It’s a lot more promising way out of debt for more people than this debt buyback scheme. And here’s some testimony from someone who went through the process a bit over a decade ago—a passage that did not survive the manual’s editing process:

At the mere suggestion by a friend who claimed to know of a lawyer who could help me by declaring bankruptcy, I immediately felt a sense of relief. It made no sense that I was in this situation. I did not buy one thing that I didn’t need. It was extremely demoralizing. So I borrowed the amount for the small fee this lawyer asked for and was soon set free of that godawful ball and chain. And now my credit record is impeccable, and delivered from all that worry.

And another of Konczal’s “more important” worries is “whether or not this will build a community of people committed to the cause going forward.” Uncanny, since I said something very much like this myself:

It’s also difficult to imagine an organized political movement emerging from it. One of the beauties of the various Occupy encampments around the country is that it created deep bonds among participants that last to this day. These ties were the reason that Occupy Sandy emerged so quickly in New York in the wake of the hurricane. But the Rolling Jubilee operates largely through murky, near-anonymous secondary debt markets and through the media. It’s difficult to explain in itself, and it doesn’t lead easily into a discussion of larger issues of political economy. And it doesn’t create organization or social ties: even if the relieved debtors knew about their liberation, which they well might not, it would be viewed more as a deus ex machina than a political act.

Finally, I resent the hell out of the implication that I don’t care about people’s suffering, assuming that’s what it is, since it’s often hard to parse the prose in this post (though the Marx-baiting sneer is clear enough):

It’s fun to imagine people writing hostile comments on that 99% tumblr saying that all these people’s misery is not useful to the cause because it focuses on the sphere of circulation instead of the sphere of production. But this is what is behind young people’s suffering and it is an important project to address it as such.

Really, Mike, if I didn’t care, I could have chosen a more lucrative and/or less aggravating line of work. I’ve tried to be very comradely in my criticisms; you could too.

The debt obsession

As I was electronically discussing my comments on the Rolling Jubilee yesterday, I got an email from Fix The Debt, the deficit-obsessed austerian group founded by Erskine Bowles and Alan Simpson. Bowles and Simpson are, of course, the deficit scolds who led the failed commission created by Barack Obama in 2010 whose mission was to lead the U.S. back to the path of fiscal rectitude.

And though the StrikeDebt! people have little in common with that gang of ghouls who want to cut Social Security and Medicare, they do share one feature: an obsession with debt. (I want to say again that I like and admire the people who conceived this project, and I offer these criticisms in a comradely, not hostile, spirit.) Instead of talking about the challenge of recovering from the after-effects of the Great Recession, of thinking how to provide people at all stages of their lives with material comfort and security, of how to humanize our mad systems of health care and education finance, of how to deal with climate change, both parties focus on debt as central to everything.

There’s an old saying in the public opinion business: we can’t tell people what to think, but we can tell them what to think about. The orthodox are constantly telling us to think about debt. But aren’t radicals supposed to challenge that discursive tyranny?

Rolling Jubilee: PS

Some follow-ups to yesterday’s Rolling Jubilee post (“Rolling where?”):

• A correction: they’re not buying credit card debt—they’re buying medical debt to start with. Several RJ people complained about this bit of misinformation, saying that it was “widely known.” It’s not on their rather sparse website though, so it’s not clear how this widely disseminated information has been disseminated.

• There were also quite a few complaints about my missing how the campaign did indeed point to a larger strategy, including a wider conversation about debt as a symptom of a larger disease rather than the disease itself. Partisans point to this sentence on the website: “We believe people should not go into debt for basic necessities like education, healthcare and housing.” Well, yes, but that’s 16 words—and it immediately segues into “a growing collective resistance to the debt system.” But debt is only one part of the system—a competitive system built around wage labor which is always, by definition, inadequate to needs. Debt can often be a supplement to paltry wages, but that doesn’t make this a debt system.

• As I said yesterday, this obsession with the centrality of debt reflects Occupy’s inheritance of American populism’s emphasis on finance at the expense of how finance fits into a larger system of production of ownership. But I suspect it’s not just populism—it’s the influence of David Graeber’s book Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Graeber’s book has many virtues—and I mean that, it’s not just boilerplate—but it offers somewhere between little and no analysis of how debt works in capitalism. (See Mike Beggs’ review for more.) Debt (or credit, to use the more upbeat word) allows people and businesses to buy things beyond the limits of current income, which means that while many people view it as nothing but a burden, many others view it as a way to buy cars, houses, and capital equipment that they couldn’t afford out of the cash lurking in their pockets. And since one person’s debt is another’s asset, it becomes a repository of savings, and not just the savings of the proverbial 1%. Any serious debt strike—one that was more than symbolic, meaning measured in the billions and not the millions, much less the thousands—would threaten those savings, and be greeted by a large chunk of the population as not liberating, but dangerous.

• Speaking of popular opinion, people who have been sweating to pay their debts might not view the deliverance of the heavily indebted as a cause for celebration. They might view it as unfair. Debt aggregates are typically driven by a minority of very heavily indebted people or businesses, and simple averages can be very misleading.

• It’s really difficult to see how the buyback scheme leads to a larger conversation about debt. It’s also difficult to imagine an organized political movement emerging from it. One of the beauties of the various Occupy encampments around the country is that it created deep bonds among participants that last to this day. These ties were the reason that Occupy Sandy emerged so quickly in New York in the wake of the hurricane. But the Rolling Jubilee operates largely through murky, near-anonymous secondary debt markets and through the media. It’s difficult to explain in itself, and it doesn’t lead easily into a discussion of larger issues of political economy. And it doesn’t create organization or social ties: even if the relieved debtors knew about their liberation, which they well might not, it would be viewed more as a deus ex machina than a political act.

• Call me old-fashioned, and I’m sure many have already done so, but I think that a discussion of those larger issues—stagnant wages, high unemployment, a crazy system of health care finance, madly expensive higher education—would lead inevitably to making demands on the state. (So too would debt relief: it would be a lot more powerful and effective if the Federal Reserve and the Treasury were buying bad debt and liberating debtors with their vast resources rather than a volunteer effort raising funds through Paypal.) And given the prominent role that anarchists and anarchism play in the Occupy movement, there’s not much inclination to make demands on the state. But what other institution in this society could raise the minimum wage, make it easier to organize unions, fund a Green New Deal to address climate change and create decent jobs, create a single-payer health care system, and provide universal free higher ed? The lack of those things in this very rich society contribute a lot to debt and deprivation. But that lack is not the product of a “debt system.”

I am very willing, eager even, to be proven wrong. So should this thing take off in fruitful ways, I will happily eat my words—and my hat too, with a side of crow.

Rolling where?

Rolling Jubilee (RJ) has certainly gotten a lot of attention in the few days since it was launched. An initiative of Strike Debt!, an offshoot of Occupy Wall Street, the Jubilee describes itself as

a…project that buys debt for pennies on the dollar, but instead of collecting it, abolishes it. Together we can liberate debtors at random through a campaign of mutual support, good will, and collective refusal. Debt resistance is just the beginning. Join us as we imagine and create a new world based on the common good, not Wall Street profits.

Anything that attracts attention to the burden of debt and the potential of liberation from it is admirable. But it will not surprise regular readers to learn that I’ve got some serious reservations about the project.

A few words first on the mechanics. Banks and other creditors typically try really hard to collect delinquent debts, but when they give up all hope, they write them off and typically sell the claims for pennies on the dollar to collection agencies and other financial vultures. The new holders are often relentless and ugly in their pursuit of debtors in default. If they bought the bad debt for two cents on the dollar, they’re happy to get five—they’ve more than doubled the money, though they do have to pay the call centers that do the ugly work of harassment. The tools of the trade are relentless threatening phone calls. Many of these techniques are technically illegal, but the law rarely stops a collection agency. According to Strike Debt!, about 15% of Americans are being pursued by collection agents, and there’s no reason to doubt their numbers.

Strike Debt!’s strategy is to raise money from generous sympathizers and buy the debt from the collection agents and then just wipe it away. Debtors might not even know what’s happened—they tell me they’re reluctant to track down the debtors they’ve delivered from harassment, and in many cases might not even be able to—but the phone calls will at least stop.

Sounds great, right? And the scheme has gotten some great buzz. Blogger Alex Moore writes that it’s “a great new answer to all the doubters who ripped on them over the past year for not having a specific enough plan.” To Guardian blogger Charles Eisenstein, it’s a “genius move” with “significant transformative potential.” Celebrants, though, are rather vague on the mechanisms by which the transformation will occur.

So far, both Rolling Jubilee and the commentators have been rather light with numbers. As I’m writing this, RJ has raised $137,688. Since they figure they can buy bad debt for about five cents on the dollar, that means they could “abolish” (the evocation of the anti-slavery movement is no accident) $2,758,584 in debt. Though they don’t say, it’s almost certain that the debt they aim to buy is the credit card kind. Student debt, even if delinquent, isn’t sold into the secondary market. Debt backed by things—as auto loans are by vehicles and mortgages by houses—aren’t generally sold that way either, because lenders can seize the underlying assets. Though there are other kinds of unsecured personal loans (those backed by pledges only, and not things), the bulk of them are credit cards, so we’ll do the math on them.

According to the FDIC, there was $664.3 billion credit card debt outstanding in the second quarter of 2012. Of that, $16.5 billion was 30 days or more past due. Banks had charged off $8.5 billion. They’re required by regulators to do that once an account is 180 days past due, but that doesn’t mean the debt is extinguished. Though the bank removes the asset from its balance sheet and takes a (tax-deductible) loss, the debt still exists. The bank can try to collect it on its own, or sell the bad debt to the vultures described above.

Let’s think about that $8.5 billion. The people who owe that money are probably getting threatening communications from the banks or whoever now holds the claims. If RJ could raise $1 million—they’re more than 1/8th of the way there now—they could buy $20 million in debt, or 0.2% of what’s been charged off. To buy all the charged-off debt at five cents on the dollar, they’d need to raise $423 million. But of course if any more than notional amounts of money were put to this task, the price of the debt would rise dramatically. To buy a tenth of it at ten cents on the dollar they’d need $85 million. In other words, given those sums, the monetary angle for RJ is purely symbolic.

What about larger political points? Strike Debt! says its aim is:

to build popular resistance to all forms of debt imposed on us by the banks. Debt keeps us isolated, ashamed, and afraid. We are building a movement to challenge this system while creating alternatives and supporting each other. We want an economy where our debts are to our friends, families, and communities — and not to the 1%.

Totally marvelous. No argument from me about the goal. But why the intense focus on debt and its relief? Debt could be an excellent point of entry into a discussion about many other things. Why so much personal debt? Because wages are stagnant or down, unemployment is high, yet the cost of living continues to rise. Why so much mortgage debt? Because until sometime in 2007, housing inflation (meaning tax-subsidized homeownership) was practically the American national religion. Why so much student debt? Because higher education is too expensive—in fact, it should be free. Etc. But Occupy has inherited a lot of American populism’s obsession with finance as the root of all evil, without connecting it to the rest of the system.

And their call for debt repudiation also seems not to have been fully thought through. The world economy nearly collapsed a few years ago because maybe 10% of debtors were unable to service their debts. If we were to return to something like that, we’d return to the verge of collapse or beyond. And such a collapse wouldn’t hurt just the 1%. Workers’ pensions would be jeopardized. Banks would fail, and millions could lose their savings. Unemployment would rise towards 1932 levels of 25%. If you’re jonesing for systemic collapse in the hope of building something better out of the rubble, then be honest about it. But don’t expect to get much support for the agenda.

A more fruitful approach to lightening the burden of the heavily indebted would be to proselytize on behalf of filing for bankruptcy. Another project of Strike Debt! is their Debt Resistors Operations Manual. Here’s their description of the manual:

You’ll find detailed strategies and resources for dealing with credit card, medical, student, housing and municipal debt. Also included are tactics for navigating the pitfalls of personal bankruptcy, and information to help protect yourself from predatory lenders. Recognizing that individually we can only do so much to resist the system of debt, the manual also introduces ideas for those who have made the decision to take collective action.

There’s a lot of good stuff in there. But the chapter on bankruptcy is larded with unnecessary warnings and complications. I know, because I wrote the original draft and watched it get deformed by group editing. The opening sentence is a fine example: “Bankruptcy, for some people, sometimes, can be a way to fight back against the creditors and escape a life of indebtedness.” No, bankruptcy is much better than that. My original opening read: “Unlike the other chapters in this manual, which are organized around ways the rich screw debtors (and how debtors can get back at them), this one is almost entirely about how debtors can screw the rich—filing for bankruptcy. To get right to the point: if you have a serious problem with credit card debt, there is absolutely no reason you shouldn’t think seriously about doing that.” Much better, I think.

And the chapter concludes by saying that it’s an unsatisfactorily individualist solution to a collective problem—which is true in some sense, but not of much help to millions suffering from credit card debt today. Many people are unaware of what a deliverance a bankruptcy filing can be, and many others are inhibited by shame. They shouldn’t be. And filing for bankruptcy has a lot more to offer than some lightly funded scheme to buy bad debt on the secondary market. Why the Strike Debt! collective chose to tone down my exhortations mystifies me.

I feel somewhat bad writing this critique. There are a lot of fine people trying to do good things with this initiative. But as long as it focuses on debt without using it as a portal to a larger discussion, it’s not going to do much more than generate some publicity.

Fresh audio product

Just added to my radio archives:

November 8, 2012 Sarah Jaffe on Occupy Sandy • Anne Elizabeth Moore, author of Hip Hop Apsara, on Cambodia

No show last week, alas: blown off course by Hurricane Sandy.

Much fresh audio product

Some of this just posted to my radio archives, and some of it’s been around for a while without being noted on the web page. Subscribe to the podcast (here’s the iTunes page—details on other portals on my archive page), and you’ll get the audio files right after they’re posted, instead of waiting for me to update the web index.

Note: several of these shows were fundraisers for KPFA. I’ve cut out the pleas, but if you want to keep these coming, please support KPFA.

October 25, 2012 Jodi Dean, professor of political science at Hobart & William Smith and author of The Communist Horizon, on how we need to reclaim that cuss-word and stop fetishizing “democracy”

October 18, 2012 Josh Eidelson on the Walmart strikes (his Salon stories are here) • Ethan Pollack of the Economic Policy Institute on green jobs

October 11, 2012 David Cay Johnston, author of The Fine Print, on how Corporate America rips us off

October 4, 2012 Matt Kennard, author of Irregular Army, on the neo-Nazis, gangbangers, and sad/broken people who populate our military, and the damage they’ve done and will do.

September 27, 2012 Leo Panitch and Sam Gindin, authors of The Making of Global Capitalism, on U.S. imperial power, etc.

September 20, 2012 Bruce Bartlett on his scary former GOP comrades • Jared Bernstein on income, poverty, and the 47%

Ontario today

A few weeks ago, during the Chicago teachers’ strike, I had kind things to say about education reform in Ontario after the Liberals took power in 2002 (“How much do teacher strikes hurt kids?”). The piece drew on work by the OECD, part of an attempt to refute work by Washington Post boy blogger Dylan “Minipundit” Matthews.

After posting it, several emailers and commenters noted that things have changed in Ontario, as the Liberals have embraced U.S.-style austerity. Have they ever. The government has passed a monstrosity with a name that Rahm Emanuel couldn’t improve on: “the Putting Students First Act, that freezes teachers’ wages for two years and prevents them from striking.” Students are protesting the bill, as John Bonnar noted in Rabble.ca the other day (“Bramalea Secondary School students stage Queen’s Park protest against Bill 115”). And unions are suing. But clearly the Ontario Liberals have gone from a model school reform to one inspired by the colossus to the south.

Matt Yglesias has a pleasant fantasy about investment

Inspired by Mitt Romney’s low tax rate, Matt Yglesias defends the principle of taxing investment income more indulgently than labor income. To make the argument, Yglesias spins a morality tale about two well-paid doctors, one a profligates who eats fancily and travels the globe, the other a prudent sort who builds buildings and hires people to work in them. It’s only fair, concludes our Slate pseudo-contrarian, that the prudent doc deserves a break from the tax code, since he’s doing so many other people favors.

Leaving aside the fact that the profligate supports an army of chefs and flight attendants, this is not how investment works in the world we actually live in. Most investments are in previously existing financial instruments. As Alan Abelson used to say in the old Barron’s ad, someone buys a stock because he thinks it’s going to go up—but the person he buys it from thinks it’s going to go down. Almost all corporate investment in real things like buildings and machinery is financed internally, through profits. For the last few decades, corporations have been generating more money than they know what to do with, so they’ve been shoveling out to shareholders. (See here for more.) In Romney’s case, Bain largely invested in existing corporations—turning some of them around (mostly with other people’s money) and bleeding others dry (at great profit to Bain partners).

Really, Matt, you didn’t know this?

Dylan Matthews has a rethink on teacher strikes

Last week, Dylan Matthews made some strong claims about how damaging teacher strikes were to student achievement—claims that I spent some time challenging (here and here).

He has softened his line now. Today, writing up Rahm Emanuel’s suit to have the strike declared illegal, Matthews says:

So the “clear and present danger” argument seems a more promising avenue for Rahm than the strikable issues claim. But still, the empirical burden of proof there is weighty. While there exist studies suggesting that strikes, insofar as they reduce instruction, reduce student achievement, CTU could try to poke holes in those or dispute that the standardized tests upon which they are based constitute valid evidence. It could also reasonably argue that if the strike endangers students, regular vacations must as well. Though summer learning loss is a real problem, it seems unlikely that courts would rule vacation a danger to students.

Also, days lost to the strike may be made up at the expense of vacation.

But, that aside, it’s very gratifying to see Matthews walking it back, as they say. And gratifying to know that I might have had something to do with providing ammo to the CTU. I wish all my workdays were so productive.

Thanks to Corey Robin for leaving a sickbed on Rosh Hashana to point Matthews’ post out to me.

Fresh audio product, lots of it

Freshly posted to my radio archives. Sorry, don’t know why it took so long. Very often the podcasts are up for subscribers well ahead of the web page update, though.

September 13, 2012 Josh Bivens of the Economic Policy Institute on the State of Working America • Melissa Gira Grant, author of this fine piece, on sex workers and their self-appointed saviors

September 6, 2012 Christian Parenti talks about the politics of climate change on the occasion of the publication of the paperback version of Tropic of Chaos

August 30, 2012 Joel Schalit on a militarized, post-democratic Israel • David Cay Johnston on Romney’s taxes

August 23, 2012 Keith Hampton on Facebook etc. is not turning us into alienated oddballs • Hugo Bonin of CLASSE (the union of provincial student unions) on the Québec student strikes

August 16, 2012 Michelle Goldberg on Paul Ryan • Charles Juntikka, Manhattan’s leading personal insolvency attorney, on bankruptcy (and why it makes sense to file)

Why wait a year for it to show up in the NYT?

I have uncanny experiences reading the bigtime press sometimes. I’ve complained before about how Paul Krugman brings up the rear, sometimes years after I’d written about them. See here for some examples. Or here.

The newspaper of record—do we still call it that in the post-print days?—has done it again. Catherine Rampell the other day (“Does It Pay to Become a Teacher?):

The United States spends a lot of money on education; including both public and private spending, America spends 7.3 percent of its gross domestic product on all levels of education combined. That’s above the average for the O.E.C.D., where the share is 6.2 percent.

…

Despite the considerable amount of money channeled into education here, teaching jobs in the United States are not as well paid as they are abroad, at least when you consider the other opportunities available to teachers in each country.

In most rich countries, teachers earn less, on average, than other workers who have college degrees. But the gap is much wider in the United States than in most of the rest of the developed world.

The average primary-school teacher in the United States earns about 67 percent of the salary of a average college-educated worker in the United States. The comparable figure is 82 percent across the overall O.E.C.D. For teachers in lower secondary school (roughly the years Americans would call middle school), the ratio in the United States is 69 percent, compared to 85 percent across the O.E.C.D. The average upper secondary teacher earns 72 percent of the salary for the average college-educated worker in the United States, compared to 90 percent for the overall O.E.C.D.

Me, a year-and-a-half ago (“Schooling in capitalist America 2011”):

In 2007, the U.S. spent 7.6% of GDP on education, 1.9 points above the OECD average….

Putting all that together, as the graph above shows, the share of GDP devoted to teachers’ salaries is rather low in the U.S. Big spending on teachers doesn’t necessarily guarantee good results. But this is a strange place to be directing the budgetary axe.

Teachers aren’t all that highly paid in this country. Secondary teachers with fifteen years experience earn 35% less than the average college graduate, 22 points below the OECD average, and 38 points behind Finland (see graph below). The figures are worse for primary teachers — 40% below the average college grad.

A skeptic might counter, yes, but U.S. overall incomes are higher than many foreign countries, so teachers are doing pretty well in absolute terms despite their poor standing relative to other occupations. But that skeptic would be wrong. An American primary school teacher is paid about $40 per hour of teaching time, $10 below the OECD average, and more than $16 below Finnish rates. Upper secondary teachers (see graph below) earn $45 per classroom hour in the U.S. $26 below the OECD average, and almost $37 below Finland.

And my version has more graphs too.

Teacher strike miscellany

Word is that the Chicago teachers’ strike is on the verge of settlement. That probably means that school reform will fade as a political issue, but it shouldn’t. But before it does, a few odds & ends to address.

Dylan Matthews, revisited

In my critique of Dylan Matthews’ awful bit of apologetics for Rahm Emanuel (“How much do teacher strikes hurt kids?”), I spent a lot of time on his use of Michael Baker’s NBER working paper (“Industrial Actions in Schools: Strikes and Student Achievement”) that allegedly showed damage to student test scores after a strike, using Ontario in the late 1990s as a test case. I focused on the political context of the labor strife in that time and place, which both Baker and Matthews overlooked. But I didn’t really go after the core of Baker’s argument, which turns out to be rather weak on close inspection.

Baker wrote:

The results indicate that “long” strikes, which last 10 instructional days or more, in grade 6 have significant, negative effects on grade 3 through grade 6 test score growth in reading and especially math. The impact of a strike in grade 6 on math score growth is a reduction of 29 percent of the standard deviation of test scores across school/grade cohorts. The average impact of strikes in grades 2 or 3 on score growth is small, negative and statistically insignificant, although there is some heterogeneity in the impact across school boards.

So strikes during grade 6 have an impact on grade 6 scores, but strikes in grade 3 have none? If anything, that shows a short-term effect that decays over time. Baker’s work doesn’t address at all what happened to those allegedly injured 6th graders by the time they got to 9th. And, while 29% of the SD sounds like a lot, if you look at the actual scores in the appendix of the paper, the differences are quite small.

Also, Baker’s literature review at the beginning of his paper shows mixed findings in past studies, including some papers showing no effects at all. Matthews did not mention that.

The conventions of academic writing, even of the most mainstream sort, do impose certain disclosure requirements that journalists don’t always observe.

Yglesias explains why teachers’ unions are different

In a post yesterday (“Why teachers unions are different: A reply to Doug Henwood”), Matt Yglesias takes exception to my speculation on why elite liberals don’t like teachers unions (“Why do so many liberals hate teachers’ unions?”). Boiling it down to a soundbite: unlike labor disputes in the private sector, where raises would come out of the pockets of shareholders, raises for public sector workers come out of the pockets of “taxpayers,” meaning you, me, Matt, and everyone else—mostly, that is, people of fairly modest means.

This use of “taxpayers” is a fascinating bit of ideology. Its dispersion into wide use marks a very successful deployment by the right of a very conservative notion. It is founded on a view that one lives in this world primarily as an individual, and consumes privately. Any sense of collective consumption (or investment, if you prefer), via the public budget, is ruled out. As is so often the case with right-wing concepts, reactionaries have a much clearer and more consistent sense of the politics behind their buzzword. Liberals, or neoliberals, like Yglesias import the right’s concepts without fully integrating them into their worldview. Yglesias wouldn’t support Paul Ryan’s fiscal policy, but he’s happy to use a word that’s deeply implicated in its underlying concepts.

Also ruled out in this usage of “taxpayers” is any sense of the state as a contested realm for class struggle. We’re all taxpayers—even though the upper classes, who are overflowing with money, have long been evading their share of paying for public goods like education.

In Chicago, Hyatt heiress Penny Pritzker (who hates being called an “heiress,” so: heiress Penny Pritzker, heiress heiress heiress), the 719th richest person in the world according to Forbes, has been showered with tax breaks by Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s government while she sits on the board of the public school system. In fact, she got a $5.2 million tax break for a hotel development while the schools in the immediate vicinity of the proposed development are seeing a proposed budget cut for next year of $3.4 million (“Penny Pritzker’s TIF”).

As the sociologist Rudolf Goldscheid put it, “the budget is the skeleton of the state stripped of all misleading ideology.” In this case, using the word “taxpayers” is the misleading ideology. People who can pay more to support public schools aren’t being made to pay—the very same elites (including Rahm himself) who send their kids to private schools. Which leads us nicely on to the next item.

But before we get there, Yglesias praises my critique of some public sector unions that I aired after Walker’s victory in the Wisconsin recall. But that was a critique of the unions for not making any alliance with the broad public over the quality of services, or articulating any general interest in defending mass living standards. The Chicago Teachers Union is not that kind of union at all. It has been a model of how public sector unions should act, making it clear that it’s fighting for better public schools on behalf of just about everyone. They’ve been rewarded with strong public support, especially from parents (“A new poll proves majority of parents and taxpayers approve of fair contract fight”).

Ok, now on to the next item.

radical simplicity

Finally, this (“There’s a Simple Solution to the Public Schools Crisis”):

Billionaire wise hobbit Warren Buffet once told school reformer Michelle Rhee that the easiest way to fix schools was to “make private schools illegal and assign every child to a public school by random lottery.”

I suppose this is rather, um, impractical, but it does have a marvelous clarifying simplicity about it. And watching people who are comfortable with vast disparities in schooling come up with arguments against Buffett’s proposal is very amusing.

From the vault: Class

I wrote this for The Baffler back in 1998. A little old, but still full of truth. This is what I submitted; the published version was edited modestly.

On the first page of his awful book, One Nation, After All, Alan Wolfe writes, “According to the General Social Survey, at no time between 1972 and 1994 did more than 10 percent of the American population classify themselves as either lower class or upper class.” He says this to prove that the rest, 90%, are middle class. But they’re not. Wolfe forgot to say that over the same period, half the unnamed rest called themselves, quaintly, working class.

But Wolfe is a man on a mission — to probe the middle-class American mind and find it largely free of alienation and bigotry, and to pronounce the Culture Wars largely the figment of politicans and intellectuals. Wolfe’s Americans are tolerant (except for the queers), open hearted (except for the wrong kind of immigrants), striving, and utterly depoliticized. To take the measure of middle-class thought, Wolfe and his “Middle Class Morality Project” assembled a sample of 200 people drawn from 10 suburbs, and polled and interviewed them. And since America is a suburban nation, these thoughts, such as they are, become what “we” think — a “we” as spurious as USA Today’s, and no more sophisticated.

It’s not very fruitful to kick around a bad book unless it’s representative of something, and Wolfe’s crystallizes the stupidity of so much of American political discourse. In both this book and our public speech, class almost never appears (except maybe as a lifestyle choice). Everything is framed as a “moral” issue rather than a political one, an individual question of right and wrong rather than a matter for collective action. Politics becomes a cuss word. For Wolfe’s middle-class moralists, religion is marvellous as long as it’s not “political”; ditto multicultural education, even. How can those things ever be anything but political? Don’t they involve issues of social power and prestige, of who belongs to a society and who doesn’t? But, no, Wolfe and his subjects drain both religion and multicultural education of all their interesting content, rendering each just another consumer preference, another marketing niche. After all, a little multiculturalism, says one of Wolfe’s interviewees, can help you pick the right global mutual fund!

Technically, Wolfe’s Middle Class Morality Project is a joke. His 200 respondents are meant to stand for about 50 million suburban households; his 24 black respondents get to speak for the entire “black middle class.” He scores the interviews impressionistically; there’s no way to control for, or even second-guess, his bias in drafting the questions or inventing the categories. But even if his picture of “middle-class” suburbia were accurate, it’s a stretch to call that representative of the way a mythic unitary “America” thinks. Suburbanites are less than half the U.S. population, and affluent suburbanites of Wolfe’s sort are still less. Just 1.5% of his sample has an income under $15,000, compared with almost 10% of the U.S. population; people with incomes between $15,000 and $50,000 are greatly underrepresented, and those with incomes over $50,000, well under half the population, are two-thirds of his sample. Over three-quarters are married, compared with just over half of U.S. adults, and just 1% appear to be gay.

For Wolfe, the book is an act of penitence for having rejected middle-class suburbia as a youth. Now, as a grownup, he’s discovered its charms. Wolfe has taken quite a political journey over the years. Once a radical, Wolfe moved to the right starting in the late 1980s (around the time he moved to Scarsdale). In 1989, he published a book denouncing Swedish social democracy as harmful to family values — around the time he was dean of the New School and purged the Marxists and other troublemakers from the economics department and replace them with big-name mainstreamers. Though he’s long gone, New Schoolers still use phrases like “damaging and rotten” to describe the Wolfe years. It takes some repressive effort to produce the blandness that Wolfe reveres.

Of course, Wolfe didn’t invent the middle-class thought he portrays; you do hear manifestations it all over the place, even among people who should know better (including Wolfe). These Americans are “religious,” but their religion makes no particular demands on them. It doesn’t matter what religion you are really, as long as you’re something (except an atheist, or presumably a Satanist, but that doesn’t come up). Wolfe’s people seem tolerant less out of conviction than out of indecisiveness; as he helpfully writes: “Ambivalence — call it confusion if you want to — can be described as the default position for the American middle class; everything else being equal, people simply cannot make up their minds.” No wonder politics is a bad word in their lexicon; it does require some making up of the mind. People believe contradictory or nonsensical things — they love capitalism, but hate the fact that it destroys “community”; affirmative action would be fine if it were for “everybody” — without feeling any urge to think through, much less resolve the contradiction.

Tolerance finds its limits in Wolfe-world on one topic: homosexuality. One respondent refused even to talk about the issue, while “others responded with nervous laughter, confusion, or expressions of pity.” On most issues, says Wolfe, his people feel that differences can be “talked out.” But not this one. Why? Is this good or bad? Wolfe never says; mulling this one over might get in the way of his reconcilation with suburbia.

Wolfe’s people do complain about overwork, a lack of time. Though the reasons for this are, to use that cuss word, political — a direct consequence of what the New York Times’s Germany correspondent Alan Cowell (approvingly) called “the American approach of working longer for less” — Wolfe & Co. seem to accept this state of affairs as natural, if unfortunate, like a nasty heat wave or a killer tornado. Unions are nice, but in the past, as an object of “nostalgia,” appropriate for the day when you had twelve-hour days and child labor; those things are back, but Wolfe didn’t interview too many Chinatown garment workers. Besides, “solidarity can become counterproductive,” once you understand “the need of business to adapt to changing economic circumstances.”

Wolfe fautously interprets the harried situation of his middle class as “a moral squeeze rather than an economic one,” because “to politicize family issues” would “run against the grain of middle-class sensibility.” But the amount of time people have to work and the expense and availability of child care — forces that shape “family issues” — are political from the start, and only the status quo is served by blinding yourself to that fact.

No, the American middle class, or at least Wolfe’s version of it, isn’t interested in the big questions. Their religion is tepid; their tolerance, contentless; and their taste in virtues is decidedly “modest,” “writ small.” “Virtue, like religion, cannot be equated with politics, for that would lead to division and discord.” The horror! Better to stick to the safe ground of mediocrity and mere decency.

If the American middle really is this blandly tolerant, who keeps electing all those yahoos to public office? Can’t be the downscale — they don’t vote; can’t be the upper class — there aren’t enough of them. Maybe behind the apolitical contentment lurks a lot more alienation and rage than Wolfe can see. But on the face of it, it’s amazing how much his middle America sounds like, of all things, the USSR in its heyday, post-Gulag and pre-Gorby. Here’s Henri Lefebvre’s description of the moral code of Homo sovieticus from the early 1960s:

This code can be summed up in a few words: love of work (and work well done, fully productive in the interests of socialist society), love of family, love of the socialist fatherland. A moral code like this holds the essential answer to every human problem, and its principles proclaim that all such problems have been resolved. One virtue it values above all others: being a ‘decent’ sort of person, in the way that the good husband, the good father, the good workman, the good citizen are ‘decent sorts of people….’”

Change “socialist” to “American,” and you’ve pretty much got it. Oxygen, please!

“In a nutshell,” Wolfe summarizes, “what middle-class Americans find distinctive about America is that it enables them to be middle class. Unlike India or Japan, the very rich and the very poor are smaller classes here, and opportunity enables those with the desire and the capacity to better their lot in life.” He is, of course, wrong. India is poor in absolute terms, but, according to World Bank figures, the country’s distribution of income isn’t all that different from the U.S. (The poorest fifth of Indians actually have almost twice the share of national income as the poorest share of Americans). And of all the First World countries, the U.S. has the most polarized distribution of income, the smallest middle class (measured relative to average incomes), an average level of mobility overall, and and a terrible record on upward mobility out of the income basement.

Objectively speaking, then, the U.S. is one of the most class-divided societies on earth, a fact that has faded from public discourse, though it hasn’t completely gone from consciousness. As Wolfe says (only to drop the point), “In 1939, while America was experiencing a Great Depression right out of Karl Marx’s playbook, 25 percent of the American people believed that the interests of employers and employees were opposed, while 56 percent believed they were basically the same. By 1994, when unions and class consciousness were in steep decline, the percentage of those who believed that employers and employees had opposite interest had increased to 45 percent, while those who thought they were the same had decreased to 40 percent.” Class consciousness, or at least identification, hasn’t completely evaporated.

In 1949, Richard Center asked a sample of Americans to place themselves in one of four classes — middle, lower, working, or upper. (In that order. Things listed first have an advantage.) Just over half — 51% — said working class. In 1996, the General Social Survey (GSS), a near-yearly inventory of what the masses own, think, and feel, asking substantially the same question as Center (but in order going from lower to upper), 45% said working class — after decades of farewells to the working class. An equal share said middle class; 6%, lower; and 4%, upper. Two ABC polls that year asking people to place themselves in either of two classes found 55% working class, 44%, middle. A New York Times poll that year found 8% lower class; 47%, working; 40%, middle, and 3% upper.

A look at occupational distributions suggest that some people may be flattering themselves. If you assume that the middle class, in strictly labor market terms, consists of middle managers, professionals, and the upper reaches of sales, service, and production workers, then it accounts for about 28% of the employed population. Senior managers account for an upper class of 3%. (If you want to include lawyers and doctors in the upper class, shift 1% up from the middle.) That leaves a balance of 69% working class. In the government’s monthly survey of private employers, over 80% of workers are classed as production or nonsupervisory.

Where do myths of near-universal middleness come from? In their very useful book (useful, among other things, as an antidote to Wolfe’s idiocies), The American Perception of Class, Reeve Vanneman and Lynn Weber Cannon argue that the Wolfe-ish tendency to assimilate the upper reaches of the working into a broad, prosperous, and generally content middle class is a habit of the more upscale among us. People at sub-elite levels tend to draw the major social division between the upper class and everyone else, while the elite sees a broadly prosperous middle with a small underclass beneath them. Vanneman and Cannon, working with their own original research as well as crunching the raw GSS data, show surprisingly little regional or even ethnic/racial difference in these fundamental class perceptions.

They also show that people name their class based on some rather simple criteria — one’s supervisory role at work, and, not unrelatedly, the prominence of mental rather than manual labor on the job. So a building superintendent may supervise others, but since the work still dirties the fingernails dirty, it’s basically a working class job. And while data entry may be clean, indoor work, it still involves little thought or discretion, so it too, though some might call it white collar, is still a working class job.

Vanneman and Cannon quote a steelworker from a 1940 study who put the class divide very succinctly: society is divided into the “figuring-out group” and the “handling things group.” Within those groups, he conceded, “there’s a lot of divisions too, but those aren’t real class divisions.” Further, he said, “sometimes, you know, a man who’s a real skilled artisan will be getting more money than that [figuring-out] fellow, but it isn’t always the money that makes the difference; it’s the fact that you’re figuring out things or you ain’t.” Few intellectuals who spend their life studying social organization could hardly outdo this formulation in both its precision and nuance.

So, to define “middle class” using these guidelines, you’d have to take the middleness seriously: the middle class stands between the big owners and the line workers — giving orders, yes, but also taking them, filling in the operational details for corporate strategies decided upon several notches up the executive ladder. And even the most senior executives of the biggest companies — CEOs of Fortune 500 companies — who in many ways are the embodiment of the upper class, still have to answer to their shareholders. If the shareholders have to answer to anyone, I haven’t found out who yet.

For the moment, though, we’re too busy pretending we’re all shareholders now to talk about divisions between Wall Street and almost everyone else — though it’ll be very interesting to see how that changes when the great bull market finally dies. (Will masses of dispossed mutual fund speculators take over Fidelity headquarters, demanding restitution?) But underneath the apparent placidity of American class relations, there still lurks plenty of awareness that some of us work for others of us, and that even “middle class” prosperity can be a very tenuous thing. The usefulness of books like Wolfe’s is to try to keep all that potential trouble buried under a dense layer of constructed amity and narcotic cliché.

41 Comments

Posted on October 4, 2012 by Doug Henwood

Why Obama lost the debate

This is a lightly edited version of my radio commentary from today’s show.

First, I should say that while I am not a Democrat, and never had much hope invested in 2008’s candidate of hope, I do think we’d be marginally better off if Obama won. One reason we’d be better off is that when a Democrat is in power, it’s easier to see that the problems with our politics—the dominance of money and state violence—are systemic issues, and not a matter of individuals or parties. That’s not to say there are no differences between the two major parties. The Republicans are a gang of terrifying reactionaries, which flatters the gaggle of wobbly centrists that make up the other party. But the Dems have some serious foundational problems that help explain what is almost universally regarded as Obama’s dismal performance in the first debate.

First, Obama’s personality. In an earlier life, I spent a lot of time studying the psychoanalytic literature on narcissism. It was all part of a study of canonical American poetry, where I thought that the imperial grandiosity of the American imaginary could be illuminated by examining its underlying narcissism. But all that is by way of saying I’m not using this term recklessly. I think there’s a lot of the narcissist about Obama. There’s something chilly and empty about him. Unlike Bill Clinton, he doesn’t revel in human company. It makes him uncomfortable. He wants the rich and powerful to love him, but doesn’t care about the masses (unless they’re a remote but adoring crowd). Many people seem to bore him. It shows.

And the charms of the narcissist wear badly over time. All the marvelous things his fans projected on him in 2008 have faded. He’s no longer the man of their fantasies. And that shows too.

Which is not unrelated to a more political problem. Unlike Franklin Roosevelt, who famously said that he welcomed the hatred of the rich, Obama wants to flatter them. He made the mistake of calling them “fatcats” once, so his former fans on Wall Street turned on him. That has something to do with why he didn’t mention the 47% thing, or tar Romney as the candidate of the 0.1%. That would be divisive and offend the people whose admiration he craves. FDR came out of the aristocracy, and had the confidence to step on the fancy toes of the rich now and then. Obama came out of nowhere, was groomed for success by elite institutions throughout his impressive rise, and no doubt wants some of those nice shoes for himself.

More broadly, the political problem of the Democrats is that they’re a party of capital that has to pretend for electoral reasons sometimes that it’s not. All the complaints that liberals have about them—their weakness, tendency to compromise, the constantly lamented lack of a spine—emerge from this central contradiction. The Republicans have a coherent philosophy and use it to fire up a rabid base. The Dems are afraid of their base because it might cause them trouble with their funders.

What do liberals stand for these days? Damned if I know. It’s not a philosophy you can express in aphorisms. (Yeah, politics are complex, and slogans are simple, but if you’ve got a passionately held set of beliefs you can manage that contradiction.) Too many qualifications and contradictions. They can’t just say less war and more equality, because they like some wars and want to bore you with just war theory to explain the morality of drone attacks, and worry about optimal tax rates and incentives. Join an empty philosophy to an empty personality and you get a very flat and meandering performance in debate.

Romney believes in money. Obama believes in nothing.

Most liberals want to write off Obama’s bad performance as a bad night. It’s not just that. It’s a structural problem.

Share this: