The housing boom (cont.)

Matt Yglesias responded, sort of, to my comments (“Was there a housing boom? Yes.”) from yesterday, countering his curious assertion that there was no building boom in the mid-2000s, by conceding that there was a boom in construction employment after all. But he refuses to give up on the argument that there was no building boom. A few more words on this topic before laying it to rest.

Yglesias graphs construction employment as a percentage of the civilian labor force with a line marking the average:

Before proceeding, a little overview to the employment stats. (No doubt CAP has a generous research budget, so if they want to send along a tuition check on their fellow’s behalf, that would be dandy.) Yglesias seems not to know that there are two surveys behind the monthly employment figures—one of about 60,000 households and one of about 300,000 employers (known as the establishment or payroll survey). He’s dividing construction employment from the establishment survey by the civilian labor force from the household survey. That’s unusual. The reason that the two surveys are rarely combined this way is that the concepts underlying the two are significantly different. The definition of employment in the household survey includes agricultural workers and the self-employed, who are not counted in the payroll survey.

Even odder is the use of the labor force as the denominator, since it includes the unemployed as well as the employed. (The labor force consists of those who are working or actively looking for work. The first set are the employed; the second, the officially unemployed. The unemployment rate is the number of unemployed divided by the labor force.) It would make more sense to use total employment as the denominator, but not the household version. My analysis yesterday took construction employment as a share of total employment from the establishment survey, which is the right way to go about this.

All that geekiness aside, Yglesias’ graph does show a marked elevation around 2005–2006. When I reproduce his numbers, I see construction employment as a share of the civilian labor force peaking at 5.4% in the spring of 2006, which is more than 20% above its long-term average. It also stayed above that average for 138 consecutive months, easily eclipsing the previous record of 75 consecutive months in the late 1960s/early 1970s. (And it was a lot further above average in the recent period than it was 40 years earlier, too.) His commentary doesn’t acknowledge the extent of the employment boom, but at least he walks back his earlier assertion, as they say in DC.

But he just won’t give up on the claim that there was no building boom, and grasps instead at remodeling. To reprise a couple of points from yesterday’s post: 1) As a share of GDP, residential investment—that is, the building of new houses and work done on older ones—hit a peak of almost 60% above its long-term trend in the mid-00s. And, 2) between 2001 and 2006, residential investment accounted for 12% of GDP growth, twice its share of the economy. If “60%” and “twice” don’t sound like big numbers, then I don’t know what does.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics also reports finer detail on construction employment (from the establishment survey), though data for most of the subcategories begins rather recently, making long-term comparisons impossible. Still, residential construction as a share of total employment peaked at 24% above its long-term average in 2006 (it’s now 30% below). Single-family contractors peaked at almost 30% above average; it’s now almost 40% below. And residential remodeling peaked at about 25% it average; it’s still slightly above that average now. A lot of the boom in mortgage debt mid-decade came from people borrowing against their inflated home equity values and using the proceeds to spiff up the kitchen or add a wing to the house. But clearly there was a lot of new building going on—much of it McMansions and other bloated structures, whose size is missed in a simple tally of starts.

Finally, the four major housing bubble states—Arizona, California, Florida, and Nevada—saw their total employment rise by 9% from the 2003 trough to the peak in 2007; the other 46 states gained just 6%. And the Bubble Four got hammered in the recession, with employment falling by almost 10%, compared with just over 5% for the other 46. The Bubble Four contributed 35% of the employment loss during the recession, nearly twice their 19% share of employment going into the downturn. The housing bubble had a lot of spillover effects, notably the use of home equity lines of credit to pay for everything from wide-screen TVs to dental work. But the direct effects of the building boom were considerable—as are those of the building bust.

Does productivity = unemployment?

There’s a controversy aflame in the left–liberal blogosphere around a revelation in Ron Suskind’s new (and apparently error-riddled) book, Confidence Men. (Brad DeLong has the page.) Suskind reports on tense high-level meetings within the Obama administration as it became clear that the StimPak wasn’t really working. Unemployment was drifting higher, and the Keynesian faction—Christina Romer, then chair of the Council of Economic Advisors, and later Lawrence Summers, then resident wise man—was calling for more stimulus. Obama said no. It was politically impossible, but Obama also argued that the productivity revolution has made workers obsolete. Against that, a few hundred bill in further stimulus—which would be DOA in Congress in any case—would do little.

Romer and Summers (who, it hurts to say, has been looking pretty good recently) argued that productivity need not create unemployment. After Obama supported an orthodox briefing by former OMB head (and inexplicable sexpot to some) Peter Orzag (who also recently said that we need less democracy to have a sensible fiscal policy), Romer objected, urging a more expansive fiscal policy. Obama cut her down in what Suskind calls “an uncharacteristic tirade.” A few months later, with unemployment now over 10%, Summers essentially made Romer’s earlier argument, and Obama listened “respectfully.” After the meeting, Romer said to Summers, “Larry, I don’t think I’ve ever liked you so much.” He told her that the feeling would pass—but then noted that Obama had been a lot more “generous” with him than her. When you’re on the wrong side of Larry Summers on feminist issues, you’ve got a serious problem.

Matt Yglesias assures us that his conversations with administration officials report that Summers and Romer won the productivity=unemployment argument eventually, and convinced him that the problem was low demand, not high productivity. But Yglesias himself also reports on an interview that Obama gave in June in which he blamed ATMs for high unemployment. And airport self-check-ins too. Stuff like that, that any globetrotter sees. So apparently Obama still believes that there’s only so much gov can do because all these business geniuses are using machines so cleverly.

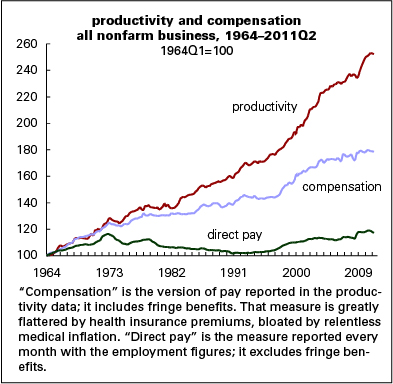

Respectable Keynesians argue that the problem is demand, which is a cyclical argument more or less, while the productivity story is more structural. But maybe both sides are right in a way. Productivity is way up but wages are flat. Workers have seen little of the productivity revolution.

The canonical tech-driven productivity acceleration took hold around 1995. From then until the cyclical peak year of 2007, productivity growth averaged 2.6% a year—4.3% in manufacturing. Compensation, which includes fringe benefits (see graphic caption), rose 1.7% a year—and 1.5% in manufacturing. Direct pay overall rose 0.9% a year—0.3% for factory toilers. During the recession, productivity growth slowed, employment collapsed, and wages rose modestly. In the “recovery years” of 2010 and 2011, productivity growth—this time not from a tech revolution but from sweating a shrunken workforce harder—has resumed growing at a 2.6% pace (2.1% is the very long-term average, by the way). But both compensation and direct pay have fallen by an average of 0.3% a year.

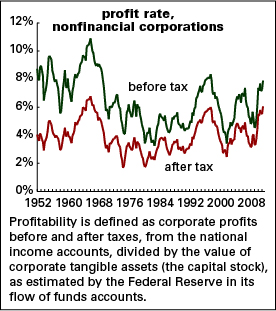

If workers were paid better, there wouldn’t be so much of a demand problem, would there? But then we stumble upon a contradiction: the entire recovery in corporate profitability that began in 1982 came from squeezing wages and workers. The trajectory of profit expansion is very uplifting—returns are roughly double what they were in the early 1980s:

After the profitability collapse of the 1970s, things began to turn around as the Volcker recession and the PATCO firing transformed capital–labor relations. Corporations enjoyed dramatically improving returns from the early 1980s through the late 1990s. Profitability took a major hit in the early 2000s recession, with the bursting of the tech bubble, but it recovered, only to stumble again in the 2007–2009 recession. But it’s staged a remarkable recovery. In the second quarter, nonfinancial firms were more profitable than they were at any time since 1997, in the frenzy of the dot.com moment.

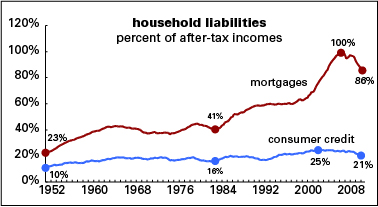

For most of the last 30 years, much of the working class was able to borrow what it wasn’t earning to make ends meet. Household debt rose strongly:

Mortgage debt rose from 41% of after-tax income in 1983 to 100% at the 2007 peak. It’s since come down hard, and the economy and political mood show it. Consumer credit—auto loans and credit cards and such—went from 16% to 25%. It’s come down too.

So here’s the demand problem: there’s no longer an endless supply of easy credit to make up what’s not in the paycheck. The greatest product of the productivity revolution is the production of profits, which has enabled a vast upward distribution of income and wealth. No one really wants to touch that one. So what’s a capitalist order under no serious political challenge to do except dither and squabble?

Was there a housing boom? Yes.

Matt Yglesias, striking that contrarian tone beloved of bloggers (something you’d never find here, of course!), declares that there was no housing boom. Or, more precisely, though there was a boom in house prices, there was no boom in construction.

To make this point, Yglesias uses one on those ubiquitous St. Louis Fed graphs, this one of the history of housing starts since 1970. Sure enough, it sorta supports his point.

But this is only a very partial view. Here’s a fuller one.

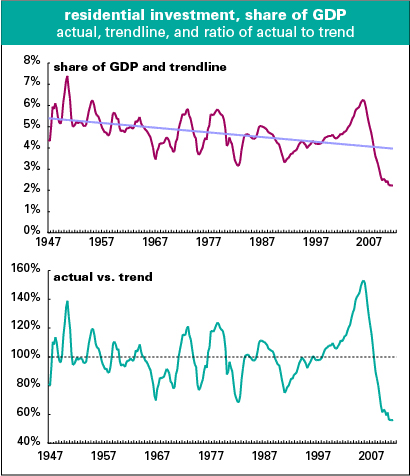

First of all, the boom wasn’t just about new houses—there was a lot of renovation and expansion of existing housing stock. That sort of thing, as well as new construction, is included in the category residential fixed investment in the national income accounts. As the graph below shows, this rose strongly in the late 1990s and early 2000s:

But note the blue trendline on the upper graph: housing’s share of the economy, despite cyclical ups and downs, has been in a steady decline since the highs of the early post-World War II years. The late 90s/early 00s boom was a sharp departure from that downtrend. The lower graph shows the relationship of the actual level to that underlying trend—when it’s above the 100% level (dotted horizontal line), it’s above trend. At the peak in 2005, the housing share of GDP was almost 60% above trend, a record by a comfortable margin. It was also above that trendline for a long time—from 1998 to 2007. Most earlier soujourns above trend were less than half that long. It’s since fallen dramatically, to almost 50% below trend, and it’s likely to stay there for some time.

Construction’s share of employment tells a similar story—

—that is, a declining trend from the mid-1950s through the mid-1990s, followed by a long spike, and then collapse. At the peak in 2006, construction’s share of total employment came close to matching its all-time high, set in 1956, during the post-World War II building boom.

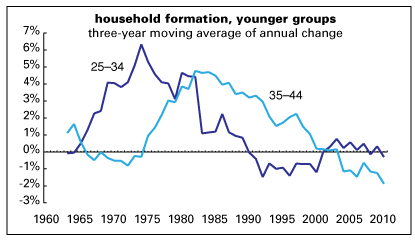

And finally, this boom came despite a low level of household formation among those aged 25–44. The boom in younger household formation in the 1950s and 1960s drove that building boom. But this time around, the building wasn’t to accommodate a population bulge, but to satisfy a lust for more space, often far from town. Between 1973 and 2007, the size of the average house increased by almost 50%, while average household size fell by 15%.

So yes, there was a building boom. Between 2001 and housing’s 2006 peak, residential investment accounted for 12% of GDP growth, twice its share of the economy. And it’s led the way down, too. And it’s helping to keep us here.

Fitch memorial this Sunday

A reminder that the memorial to the wonderful Bob Fitch, who died in March (my remembrance of him is here), is this Sunday, 4–6 PM, at the Brecht Forum, 451 West St (between Bank & Bethune), Manhattan.

New radio product

Freshly posted to my radio archives:

September 10, 2011 Mike Lofgren, former Congressional staffer and author of this spirited farewell to his long-time party, describes the furious insanity of the GOP • Jonathan Kay, author of Among the Truthers, and Kathy Olmsted, UC–Davis prof and author of Real Enemies: Conspiracy Theories and American Democracy, on conspiriacism, esp the 9/11 kind

Me on Al Jazzera English

I’m going to be on Al Jazeera English around 9 AM New York time discussing Obama’s jobs plan, such as it is.

Watch here.

Me & Graeber on the TV this weekend

A reminder: my chat with David Graeber about his new book, Book TV this weekend:

- Saturday, September 3rd at 12pm (ET)

- Saturday, September 3rd at 7pm (ET)

- Monday, September 5th at 7am (ET)

New radio product

Just added to my radio archives:

September 3, 2011 David Cay Johnston on how corps and the megarich get away with paying almost no taxes (his Reuters column on GE is here) • Adolph Reed on the Dems, the inflated threat of the Tea Party, and the diminishing usefulness of race as a political category

New radio product

Just posted to my radio archive:

August 27, 2011 Mark Brenner, director of Labor Notes, reflects on the state of labor as Labor Day approaches • Alexander Cockburn, occasional Nation columnist and co-editor of Counterpunch, on the media and the media criticism racket

Graeber & me on the TV

My interview of/conversation with David Graeber about his book Debt: The First 5,000 Years will be on C-SPAN 2’s BookTV on Saturday, September 3 at noon and 7 PM and again on Monday, September 5, at 7 AM.

Here’s the C-SPAN page: Debt: The First 5,000 Years – Book TV.

Obama’s “progressive base”

I just read this in a magazine: “Obama will also need a push from the progressive base that elected him in 2008….”

Wow. Sad. Give it up, guys. He’s just not that into you.

Me interviewing David Graeber

A reminder—this is tomorrow:

Debt

A Conversation with Doug Henwood and David Graeber

August 23, 7:30pm

Melville House Bookstore

145 Plymouth St, Brooklyn

Debt is now the central issue of our time: With the rise of cheap and unsustainable credit, un-repayable mortgages collapsed the world economy in 2008. In Europe, Greece, Spain, Ireland, Iceland and Portugal have pushed the European economy to a perilous point, threatening the Euro. And we’ve just lived through a debt crisis of our own, with congress nearly forcing U.S. default.

We’ll be joined by two guests to discuss the role of debt in the world economy: author and radio show host Doug Henwood, an expert on bubble economics and Wall Street, and anthropologist David Graeber, who has just published a history of debt from ancient Mesopotamia to the present day, Debt: The First 5,000 Years.

New radio product

Freshly posted to my radio archives:

August 20, 2011 Max Ajl, the Jewbonics blogger, on why Israelis are in the streets and how talk of the Occupation is not welcome • Yanis Varoufakis updates the eurocrisis as it spreads westwards

New radio product

Freshly posted to my Radio archives:

August 13, 2011 Dacher Keltner of UC–Berkeley on the psychology of class and social interactions • David Graeber, author of Debt: The First 5,000 Years, provides an anthropologist’s POV on money and debt

July 30, 2011 Joel Schalit on Brevik, the European right, its attitude towards Israel, and Israel’s own right • Brad DeLong on the political economy of austerity

The audio files are often posted far more promptly than I update the web page, so if you’re into timeliness, subscribe to the podcast!

Christian Parenti in NYC

Alas, we’ll be out of town, but everyone without an excuse must go to this:

Tropic of Chaos

Christian Parenti in conversation with Vijay Prashad and David Harvey

Sponsored by the Center for Place, Culture and Politics

Co-sponsored by the Center for Humanities at the GC and The Brecht Forum

Monday, August 29, 2011 from 7-9 pm

The James Gallery

CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue @ 34th Street

In Tropic of Chaos: Climate Change and the New Geography of Violence (Nation Books; July 1, 2011), award-winning writer Christian Parenti argues that the new era of climate war has begun, intertwining environmental disasters, poverty, social inequality, and violence in the Global South. Parenti, historian Vijay Prashad and Marxist scholar David Harvey will discuss the historical legacy of Cold War militarism, neoliberal economic restructuring, and the convergent onset of climate change expressed as warfare, crime, repression, state failure, and a planet in peril.