Ciao, public option

So it’s looking like Obama’s not only dropping the public option, he may be using the rejection as a way of distancing himself from the “left.” As Politico reports:

On health care, Obama’s willingness to forgo the public option is sure to anger his party’s liberal base. But some administration officials welcome a showdown with liberal lawmakers if they argue they would rather have no health care law than an incremental one. The confrontation would allow Obama to show he is willing to stare down his own party to get things done.

It’s all about “choice and competition,” you see. Forget about the experience of all those funny foreign countries!

PS: When’s the last time a Republican “stare[d] down his own party to get things done”?

Tongue-tied liberals

Every passing day reveals the toxic side-effects of the Obama presidency more clearly. The activist liberal left has largely either gone silent or cast itself in the role of apologist for power.

Let’s look at two sad examples. First, the war in Afghanistan. The other day, the New York Times reported that the antiwar movement plans a nationwide campaign this fall against the administration’s escalation of the war in what we’re now calling AfPak. Among the challenges facing the campaign, aside from the usual public indifference when it’s mostly other people being killed, is that “many liberals continue to support Mr. Obama, or at least are hesitant about openly criticizing him,” in the words of the reporter, James Dao.

Armed with a magnifying glass, Dao spied some signs of a growing disenchantment among liberals with their Pentagon- and Wall Street-friendly president. But such disenchantment has its limits, at least for now. Ilyse Hogue, a mouthpiece for MoveOn.org, disclosed that “There is not the passion around Afghanistan that we saw around Iraq. But there are questions.” How’s that for boldness? Questions.

Robert Greenwald, most famous for his anti-Wal-Mart movie, is now doing a documentary called Rethink Afghanistan, which is being released serially on YouTube and the like. Greenwald says his approach is “less incendiary” than the Wal-Mart film. “We lost funding from liberals who didn’t want to criticize Obama,” says Greenwald. “It’s been lonely out there.” Well-off liberals are entirely comfortable blasting Wal-Mart, which is vulgar and largely Republican. But don’t be too bold in criticizing—I mean questioning—our president, who is an elegant Democrat.

And then there’s health care. The Internet and the liberal weeklies are full of defenses of ObamaCare against the slurs of the right. Now there’s no denying that some of those slurs are truly demented concoctions. And there’s no doubt that Obama’s harshest critics on the right are racists, xenophobes, and mouth-breathing reactionaries who move their lips when they read. No doubt. They’re now the major source of Keith Olbermann’s nightly material.

But you’d be hard pressed to find a liberal who could actually explain the substance of the health care proposals, or even tries to. They’re presumed to be good, just because they come from “our” guy and they’re wrapped in expansive rhetoric that effectively disguises their corporate-friendly content.

And the quality of much of the opposition has only deepened the liberals’ defensive ardor. A few weeks ago, I heard someone I love and respect, an otherwise sophisticated and thoughtful person, say that “we” have to support the scheme just because “they” oppose it. Professional journalists, who should know how to scrutinize the content, typically do little better. So we’re condemned to dueling caricatures, and our health care system will continue to suck enormously.

Inbox contradictions

Within minutes of each other this morning, I got two emails on the state of the world economy.

One, from In Defense of Marxism (such is the political scene that even Marxists are on the defensive—doesn’t anyone even dream of revolution anymore?), The Unfolding Capitalist Crisis – a nightmare for workers everywhere. Its nut graf: “[I]n many ways the present crisis is potentially even more serious than that of 1929-33. Its scope is much wider than the thirties and its impact has been far swifter.”

And, from a completely different perspective, this from Wall Street’s favorite economist, Ed Hyman of ISI: “Unprecedented synchronized global upturn…. To an unprecedented extent economies are recovering across the world at the same time.”

Which is it? My guess is somewhere in between. Hyman’s upturn is a bounce off a sharp decline, while Marxists.com’s analysis consists heavily of anxious quotes from bourgeois pundits uttered during that sharp decline, from December 2008 to June 2009. Average the two and you get a long period of a crappy global economy.

Radio commentary, August 27, 2009

Not all that much to say. The economy continues to stumble along, not really declining, but not really improving either. First-time claims for unemployment insurance fell by 10,000 last week, but remain quite elevated. On a graph, the picture is of a distinct improvement during spring and early summer, followed by a stall. The number of people continuing to draw benefits fell by 119,000 the week before (the continuing claims numbers are always a week behind the initial claims figures), but they too remain quite elevated, and are only in the mildest of improving trends. And some of that decline may be the result of the unemployed running out their benefits rather than getting new jobs.

In other labor market news, last week, the Bureau of Labor Statistics issued its quarterly report on gross job flows. The familiar monthly employment numbers are the rather placid-seeming net results of massive turbulence—literally millions of jobs created less millions of jobs destroyed every month. Unfortunately these numbers are only available with an eight-month delay, so we’re only just learning what happened at the end of 2008. Still, the story is pretty compelling. In the last three months of 2008, there 6.7 million jobs created in the private sector (a combination of existing employers expanding and new ones sprouting up), and 8.5 million jobs destroyed (through layoffs and business failures), for a net change of -1.8 million. In percentage terms, the net change was the worst since the series began in 1992. But it wasn’t the gross losses that set a record—the end-2008 figure was well below the damage done in the third quarter of 2001. The real outlier was the weakness in gross gains, which set a new low by a comfortable margin, capping a two-year downtrend. Employers never went on anything like the 1990s hiring spree during the recent expansion—and now they’re not hiring at all.

Compared with the early 1990s recession, job losses in this downturn have come more from contracting establishments than from outright closures. That may help explain the recent strength in the productivity numbers—which is amazing. Employers are laying off workers and forcing the remaining staff to work twice has hard. In the bloodless world of numbers, that appears as an acceleration in productivity. To use the old language, it’s an increase in the rate of exploitation.

That’s been very good for profits. On Thursday morning, the Bureau of Economic Analysis reported strong corporate profits figures for the second quarter of this year. That’s a remarkable performance in such a deep recession. And what profits damage occurred last year was mostly in the financial sector—which now looks to be recovering. In fact, the scuttlebutt on Wall Street is that the big banks are making scads of money, but they’re going to try to hide it through accounting tricks so as not to attract bad publicity.

It’s amazing that despite the severity of this recession, almost nothing has changed in the broad economic or political structure, or in popular or elite consciousness. Which makes me wonder if this is really all over, or just the eye of the storm.

Fresh audio

Just posted: my August 27 radio show.

Ned Sublette, author of The Year Before the Flood and The World That Made New Orleans, on that city, its culture and music, and the aftermath of Katrina (plus the radio premiere of his song, “Between Piety and Desire”) • Adolph Reed on the dismal state of the left and the waning usefulness of “race” as a category

Get your LBO sample here

Article from LBO #119 freshly posted to the web: Americans: sick, poor, undereducated, overworked, smug. Or, “How American awfulness stacks up.” A review of the OECD’s latest Social Indicators, showing just how bad off the USA is compared with most other rich countries in a host of important ways.

We post samples from LBO to the web for free consumption—but only a few, and with a delay. If you like what you see, subscribe.

De mortuis: Teddy Kennedy & dereg

According to just about everybody, Teddy Kennedy represented the “soul” of the Democratic party, which presumably refers to his long-professed concern the poor and the weak. Now that that soul is safely buried, the Dems can move on to the important stuff, like preserving Wall Street power and escalating the war in Afghanistan.

Let’s inspect that soul a little more closely though. I’ve never been inclined to hold my tongue about the recently departed. Well, yes, in personal life, but certainly not public life—especially in the midst of one of these orchestrated rituals of national morning that have become so damned compuslory since Ronald Reagan went on to his reward.

Sure, Teddy had his virtues, especially in contrast to his older brother John, who could wage imperialist war with the best of them, and who’s revered by supply siders as their political ancestor. (Since we’re talking politics, not personality, let’s bracket that little incident where Teddy drunkenly drove a woman to her death, left the scene of the crime, and then dispatched a family laywer to get to the Kopechne family before the press did. One can only imagine what went on at that meeting.) Let’s just look at Teddy’s role in one of the greatest assaults on working class living standards of the modern neoliberal era, transport deregulation.

Once upon a time, working for an airline or driving a truck was a pretty good way to make a living without an advanced degree: union jobs with high pay and decent benefits. A major reason for that is that both industries were federally regulated, with competition kept to a minimum. Starting in the early 1970s, an odd coalition of right-wingers, mainstream economists, liberals, and consumer advocates (including Ralph Nader) began agitating for the deregulation of these industries. All agreed that competition would bring down prices and improve service.

Among the leading agitators was Teddy Kennedy. The right has been noting this in their memorials for “The Lion,” but not the weepy left.

Why was Kennedy such a passionate deregulator? Greg Tarpinian, former director of the Labor Research Association who went on to work for Baby Jimmy Hoffa, once speculated to me that it was because merchant capital always wants to reduce transport costs—the merchant in question being Teddy’s father, Bootlegger Joe. Maybe.

In any case, Kennedy surrounded himself with aides who worked on drafting the deregulatory legislation. Many of them subsequently went on to work for Frank Lorenzo, the ghoulish executive who busted unions at Continental and Eastern airlines in the early 1980s. (Kennedy’s long-time ad agency also did PR work for Lorenzo.)

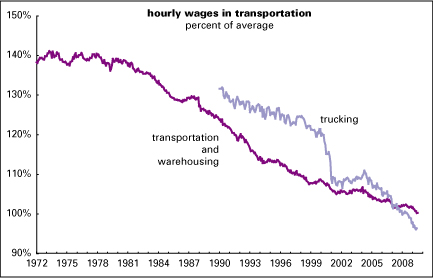

And what was the result of all this deregulation? Massive downward mobility for workers. The Bureau of Labor Statistics doesn’t provide earnings data for the airline sector, and its data on trucking only begins in 1990. (Start search for data here.) So for a longer-term view, we have to look at the entire “transportation and warehousing” sector (which is mostly transportation). The graph of that sector’s hourly earnings compared to the entire private sector average is below.

On the eve of dereg, hourly wages in transportation and warehousing were about 38% above average, where they had been for years. As soon as regulations were lifted, however, the averages began a long slide that continues to today. That wage premium has now disappeared completely. The pattern in trucking since the data begins in 1990 is pretty similar, going from a 32% premium in 1990 to a 4% discount today. And working conditions have gotten inexpressibly worse—longer hours, fewer benefits, less security. Perhaps there’s a perverse egalitarianism here, the dethronement of a labor aristocracy. Is that the soul of the Democratic party?

Ah, but partisans will respond, dereg has lowered costs, democratizing the formerly elite world of air travel. (Most of us have little to do with trucking, so I’ll leave that aside.) Fares are purportedly way down now that competition rules. Proponents point to their favored measure, real costs per seat mile—the inflation adjusted cost to a passenger of traveling a single mile by air. Those are indeed way down—good news if you’re a seat. If you’re an actual human passenger, however, flying today is a whole lot more challenging than it once was—more advance purchase restrictions, fewer nonstop flights, more transfers. (The last two mean that people are flying greater distances to get from A to B than they did pre-1979, so citing fares per mile is ludicrous.) Those restrictions and other unpleasantries are actually a hidden form of price increase.

The compilers of the Consumer Price Index try heroically to adjust for such quality declines. That’s why the airfare subindex of the CPI has been raced ahead of overall inflation since dereg hit in 1979. Graphed nearby are the two price indexes. Note that before deregulation, the lines moved in tandem. Since deregulation, airfares have taken off. The gap would be more impressive if it hadn’t been for the recent decline, a product of the collapse in oil prices in late 2008 and early 2009, compounded by weak demand thanks to the recession.

Since 1979, inflation in airfares has averaged 5.9% a year, vs. 3.8% for the overall CPI. From 1964, when the airfare subindex begins, to 1979, plane travel lagged overall inflation—an annual average of 4.4% for airfares, vs. 5.4% for the headline CPI.

You might think that rising prices and falling wages have been good for industry. Not so for the airlines, which are now mostly a wreck. According to the Air Transport Association, the industry as a whole lost a cumulative $40 billion since 1979. That more than offsets the industry’s total profits between 1947 (when their figures begin) through 1978. In its entire history, the U.S. airline industry has lost a total of $35 billion. Many major names have been through bankruptcy, some more than once.

What a remarkable achivement: a policy that has led to huge losses for both labor and capital. And any tribute to Teddy Kennedy that omits his prominent role in this disaster is incomplete.

LBO #120 out!

Already emailed to subscribers, and at the printer for the dead-tree crowd: LBO #120.

Contents:

Bad medicine, bad politics • That bad case of consumption • Why doesn’t USA Inc. support single-payer? • Deleveraging: how much? • Worst over—now what? • How much richer the rich have gotten

Click here for a taste. Click here to subscribe.

The reason for the prompt appearance of #120, reversing a 20-year history of missed schedules? The appointment of Liza Featherstone as counseling editrix. Many more to come…on time!

The Whole Foods brouhaha

So apparently a lot of high-minded liberals are annoyed by the reactionary WSJ op-ed written by Whole Foods CEO John Mackey. Mackey is afraid that Obamacare will take us further down the Road to Serfdom. The money quote: “The last thing our country needs is a massive new health care entitlement that will create hundreds of billions of dollars of new unfunded deficits and move us much closer to a government takeover of our health care system.”

HuffPo and Daily Kos types are doing what they do best: furiously venting in comments sections and vowing a boycott. The boycott probably an empty threat—so far, the stock market, for what it’s worth, seems to think so. But the suddenness of this attack of righteous indignation is a little strange. Mackey has long been rabidly anti-union; he once famously compared organized labor to herpes.

But the outrage is only a little strange. The NPR demographic that is the Whole Foods base has never been fond of unions. Yet you do have to wonder if the venters have any idea what’s actually in the awful health care reform bills circulating around Congress. They’re probably just outraged that Mackey’s dissing a Democrat. And we all know how much better Dems are than Republicans. Republicans are just so icky.

Radio commentary, August 15, 2009

On Wednesday, the Federal Reserve completed its regular policy-setting meeting, an event that happens every six weeks or so. The communiqué they issued after this one contained few surprises. They see the economy as leveling out, and the financial markets in an improving trend, but prosperity as anything but around the corner. More precisely, they expect economic activity “to remain weak for a time,” and anticipate that they will continue to engineer a regime of “exceptionally low,” in their phrase, interest rates. They see the risks of inflation as very low too—unlike a lot of Wall Street hawks, who are convinced, wrongly in my view, that all this government largesse will stoke the inflationary fires. (The wrongness of this was brought home by Friday’s report on the consumer price index for July, which showed prices outside energy to be almost flat.) The Fed will continue to buy up mortgage bonds—they’re now the major funder of mortgage lending in the U.S. economy, through such purchases, but they will phase out their purchases of U.S. Treasury bonds by October. That’s a month later than originally expected, but it’s still the beginning of something like the end of their extraordinary interventions in the markets that have gone on for two years now.

As regular listeners know, my view of the state of the U.S. economy is pretty similar to the Fed’s. Economist Ed McKelvey of Goldman Sachs—regular listeners also know that I’ve been pretty critical critical of Goldman’s tightness with the U.S. government, and their ability to use that relationship to make lots and lots of money, but their economists are first rate and always worth listening to—put it nicely the other day when he said that while the economy is stabilizing, it remains “vertically challenged.” Or, it’s stopped falling, but shows no signs yet of getting up.

The once indefatigable American consumer, for example, is still looking pretty tired now. On Thursday, we learned that retail sales excluding autos fell for the fifth straight month in July. The cash-for-clunkers program, that horrendous boondoggle, did stimulate some car sales, but most other categories were down. Most analysts, including me, had been expecting no change or a slight increase. The rate of decline has slowed markedly from last year’s record-breaking collapse, but we’re not seeing anything like a recovery yet.

Whenever I say things like that, I’m caught in a dilemma. Consumer spending is at the heart of our economic set-up, but in a rational world, the economy wouldn’t be so dependent on a frenzied pace of consumption. So on the one hand, I’m hoping for recovery, but on the other, I’m hoping for a long-term transformation. I don’t know how to resolve that contradiction. If you’ve got any ideas, please let me know!

In other news, we learned that bankruptcy filings by individuals rose by over 15% in the second quarter compared to the first, and by businesses, almost 12%. Personal bankruptcies are in a strong uptrend again. Filings soared in the run-up to the tightening of the bankruptcy code in 2006, as people rushed to beat th deadline, and then fell back sharply. But they started rising again almost immediately. Almost 5 out of every 1000 people filed for bankruptcy in the second quarter of 2009. That’s well below the peak of almost 9 per 1000 in the last quarter of 2005, in the last-minute filing rush, but it’s above the level we saw at anytime before 1997. The rise in bankruptcies—which, aside from being a major trauma for the people involved, can also be seen as a symptom of general debt distress and economic strain—over the last few decades is an amazing thing. In 1950, only about 2 people in 10,000 filed for bankruptcy. That rose some as the years went on, but we didn’t see 1 per 1000 until 1973. By 1990, it was almost 3 per 1000. It broke 5 per 1000 in 1997, then fell back some as the economy boomed. It rose again starting after the 2000 stock market bust and 2001 recession, peaking in 2005 just before the barbaric bankruptcy reform took effect. And, now it’s spiking again. Business bankruptcies, which were largely unaffected by the change in the law, are on track to come in at the highest level since the mid-1980s and early 1990s.

Early in the week, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that labor productivity—output per workhour—rose at a 6.4% annual rate in the second quarter, an extremely strong performance. Unit labor costs—how much employers have to pay workers per unit of output—fell by an also extraordinary 5.8%. To use the old Marxist language, these figures show that employers are coping with the recession by increasing the rate of exploitation: laying off workers and squeezing the remaining ones harder than ever. Over the long term, productivity can only grow if firms invest in equipment, which they’re not doing now. But in the short term, they can speed up the line and make one person do the job of two. And surviving workers won’t complain because they’re scared of losing their own job.

The level of fear was well measured in a recent Gallup poll, which found 31% of workers worried about being laid off, twice the 2008 level in this yearly poll, and easily the highest share since they started asking the question in 1997. Actually, this isn’t that much of a surprise. What is a surprise in the history of responses to this question is that even in relatively good times, 15–20% of workers are scared of losing their jobs. That state of fear, no doubt, brings a smile to the lips of employers—but it’s a helluva way to run a society.

And, finally, though the U.S. economy is likely to show some positive growth numbers by year-end, in an amazing development, it’s looking like the economies of Europe are doing even better. France and Germany are reporting modest growth for the second quarter, while we’re still contracting. This is a remarkable turnabout from the days when Americans routinely mocked the sluggishness of Europe and celebrated the alleged dynamism of the USA. Maybe, as a friend of mine pointed out, having a financial system that’s regulated to minimize bubbles and a fiscal system that provides generous support to people out of work really does have some economic benefits, aside from being more humane.

Liza Featherstone, counseling editrix

In LBO news—actual news related to Left Business Observer, a newsletter—Liza Featherstone has been appointed counseling editrix of the publication. Her responsibilities will include tightening and buffing the prose and disciplining the recalcitrant and tardy publication into a schedule. The masthead of #120, now in production, will reflect this change.

The staff of LBO is very excited about this development.

Radio commentary, August 8, 2009

[WBAI is fundraising this week and next. My fundraiser is next week—be sure to pledge during my slot, details to follow!—and I was pre-empted on August 6. My KPFA show for August 8 is mostly a rerun, but it did contain this fresh commentary.]

If you’re an American taxpayer, you’re an owner of AIG, the failed insurance company. According to a piece in Thursday’s Wall Street Journal (which did the research itself—God, I’m going to miss newspapers), AIG and the Federal Reserve, a branch of the U.S. government, will be paying Wall Street investment banks—familiar names like Morgan Stanley, Deutsche Bank, and, of course, Goldman Sachs—around $1 billion in fees to break the company into pieces and sell them off. More public money going to investment banks to break up a corpse that was done in because of lax regulation.

I hate to keep rubbing this in, but if this is change we can believe in, then I’m Marie, Queen of Romania.

And how about that cash for clunkers program? Almost everyone purports to hate governmment spending, but if it involves a $4,500 subsidy to buy a new car, well that’s ok! Estimates are that the first installment of the program, which cost $1 billion, moved about 180,000 units off dealers’ lots, and stimulated fresh orders from carmakers. Presumably another $2 billion, the amount of a second installement that Congress passed quicker than you can say “Free Money!,” will move twice that many. To what effect?

Not much, probably. First of all, it’s quite likely that some large but unquantifable prooportion of these sales were just moved forward from future months. But aside from the economic stimulus, getting old gas guzzlers off the road and replacing them with fresh, fuel-efficient vehicles is supposed to be good for the environment. Well, barely, if at all. According to estimates by the Associated Press, the first installment of the program is likely to save altogether the equivalent of an hour’s greenhouse gas emissions by the U.S. And that doesn’t adjust for the fact that making new cars emits a lot of greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere. It may take five or more years of post-clunker lower emissions to make up for that effect.

How will our cash-strapped leaders pay for Cash for Clunkers, the sequel? By raiding the funds for a new Energy Department loan guarantee program designed to stimulate innovative clean energy technologies. Created as part of the stimulus package, that $6 bilion program will now be a $4 billion program. So they’re diverting funds from something with considerable economic and environmental promise to finance something of dubious value. More change we can believe in!

And finally, some comments on the July U.S. employment report, released on Friday morning. It may seem a little odd to take the loss of a quarter of a million jobs last month as good news, but this is the best employment report we’ve seen in nearly a year. About half the 247,000 decline was in goods production, with construction leading the way, and manufacturing not far behind. The other half was in private services, with retail leading the way down. About the only plus signs were in health care, as usual, and leisure and hospitality rose by 9,000, thanks to performing arts and spectator sports and amusements, gambling, and recreation (suggesting that people are seeking diversion from their woes?).

Despite the improvement in July’s tone, longer-term measures still look dreadful. We’ve lost almost 7 million jobs since the recession began in December 2007, almost 6 million of those over the last year. In percentage terms, we’ve lost one and a half times as many jobs in this downturn as we did in the 1981-82 affair, which is widely regarded as the worst in modern times. Yes, the rate of deterioration in the yearly measures is slowing, but we’re not yet seeing less negative annual numbers (or, to put it more geekily, we’re not yet in the realm of the positive second derivative).

Those figures come from a huge survey of employers. The Bureau of Labor Statistics does a simultaneous huge monthly survey of households as well. That looked pretty bad. While the unemployment rate fell by 0.1 point to 9.4%, the first decline since April 2008, it looks like a lot of people have given up the job search as hopeless, meaning they’re no longer counted as officially unemployed. And the ranks of the unemployed are increasingly dominated by people who’ve been jobless for half a year or more—people whose prospects for re-employment in the future are usually quite damaged by these long spells outside the labor force.

So while there are some signs that the recession is drawing to a close—an impression confirmed by the drop in first-time claims for unemployment insurance last week—the job market is still awful, and the recovery that’s likely to follow the end of the recession sometime later this year will almost certainly be very weak and not very joyful. The U.S. economy has some serious structural problems that aren’t even being discussed, much less addressed.

20 Comments

Posted on September 4, 2009 by Doug Henwood

Radio commentary, September 5, 2009

[No, it’s not time travel. The commentary I read on WBAI on Thursday, September 3, came out before the August employment report. I added an analysis of that for the KPFA version, included here, to be broadcast on the morning of September 5.]

If you watch MSNBC, which I do most nights (before switching to Fox, because it’s so much more energetic and perversely entertaining), you’ll hear that the Republicans are unfairly demonizing a president with a fundamentally popular agenda. Uh, not exactly. Obama’s slide in the polls is actually one for the record books.

He started with a pretty high standing. Since Eisenhower, the average first-term president enjoyed a 58% approval rating in the Gallup poll. Obama’s was 8 points higher than average, 66%. George W. Bush was also at 66% as his term started. Those are among the highest figures for first-term presidents in modern history. Eisenhower was at 74%, and LBJ at 71%. But Reagan and Bush Sr were both at 51%, 7 points below average, and 15 points below where Obama started.

In the latest Gallup poll, Obama’s approval rating is down to 54%, a decline of 12 points. The average for first-term presidents is a gain of 5 points. Losses of Obama’s magnitude but him in company I’m guessing he’d rather not be in: George W had taken a 10-point hit just before Semptember 11—though his approval rating soared after that unfortunate day. Jimmy Carter took a 12-point hit in his first nine months in office. But Nixon, Kennedy, and Reagan all gained 7 to 9 points. Bill Clinton offers a more cheering precedent for Obama—though he started with an approval rating 11 points below Obama’s, he fell by almost as much during his first nine months in office, and left office as one of the most popular presidents in the history of polling.

So what’s this all mean? Though Obama’s lost a few points among Democrats, especially moderate and conservative ones, most of his erosion comes from Republicans and Independents—despite all his efforts to woo them. This suggests a few things. One is that it makes little political sense to try to win over people who are disposed to hate you. And two is that liberals are a bunch of credulous suckers. At some point, they will join those to their right in jumping ship—maybe as soon as next week, once Obama ditches the public option in his health care reform scheme. And then, maybe, politics could get more interesting.

Speaking of health care reforms, we’ve heard a lot from the Sarah Palin/Betsy McCaughey right about how ObamaCare would create death panels who’d pull the plug on grandma. Though there’s a lot to hate about the health care reform schemes, the death panel thing is a complete invention of the loony right, which either can’t tell true from false, or is happy just to make stuff up if it suits their purposes.

The other day, the California Nurses Association, a vigorous supporter of a single-payer, Canadian style system, put out an interesting study of actually existing death panels: the practices of private insurers. They found that more than one in every five requests for medical claims filed by insured patients are rejected by California’s largest private insurers. They looked at seven years of data, 31 million claims, and found that 21% were rejected, despite being for procedures ordered by licensed physicians. Some companies rejected 30–40% of claims submitted. These weren’t frivolous rejections. People died because of them. But since they’re done by private insurers, and not some phantasmic public body, Sarah and Betsy aren’t fulminating about them.

And now, a special update for the KPFA and podcast audiences. Friday morning brought the release of the August U.S. employment report. It was a mixed bag. The unemployment rate took a surprisingly strong leap, but the rate of job loss continued to slow.

Before proceeding, a technical note. The monthly employment statistics come from two separate surveys, one of employers, also known as the establishment or payroll survey, and another of households. The sample size on the establishment survey is huge—around 300,000 employers. The household sample is much smaller, 60,000 households, but that’s still 50 times as large as a typical opinion poll. Both provide pretty good estimates done in a very timely manner, but they’re not perfect—and given the smaller size of its sample, the household survey is noisier (meaning it bounces around some from month to month).

The establishment survey reported a loss of 216,000 jobs in August, a number that would normally look terrible, but is actually the smallest loss in a year. The private sector lost 198,000 jobs, also the smallest number in a year, and well below the -477,000 average for the previous six months. Construction lost 65,000—but this time, residential building wasn’t in the lead. Losses in residential construction are slowing, suggesting that while housing—an important leading indicator for the broad economy—isn’t yet turning around, the bleeding has largely been stanched. And more than a third of industrial sectors actually added jobs in August, the most in nearly a year. Normally, a third would be a terrible number, but we’ve been down so long that terrible is starting to look up to me.

Some wit or other labeled this a “mancession,” because so many more men than women have been losing jobs. (The term has really caught on: Google turns up 49,500 hits on the word.) One sign of this is that the share of women workers in the establishment survey was 49.9% in July (the sex breakdown is available only with a month’s delay). Given the recent trend, it’s likely that it hit 50.0% in August – or, if not exactly, it will in September. When the recession began, not quite 49% of workers in the payroll survey were women. Of course, this is a long-term trend – when the Bureau of Labor Statistics first started the gender breakdown in 1964, just 32% of workers were women – but it looked for a while, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, that the female share of the workforce had plateaued. But the recent disemployment of men has changed that, to the point where the workforce is almost perfectly divided between men and women (though, of course, women are more likely than men to work part-time, and to earn considerably less money: some things haven’t changed).

But the household survey was rather discouraging. The share of the unjailed adult population working fell 0.2 point to 59.2%, its lowest level since early 1984. It’s down more than 5 points since its peak in 2000. In other words, when you adjust for population growth, almost all the employment gains of the 1980s and 1990s have been reversed.

The unemployment rate rose 0.3 point to 9.7%, a surprise given the behavior of other indicators, like the weekly jobless claims numbers that I often cite here. The broader U-6 rate, which includes those working part-time because that’s all they could find and discouraged workers, who’ve given up the job search as hopeless, rose 0.5 point to 16.8%. In line with the recession’s continuing pattern, most of the rise in unemployment came from permanent job losers (as opposed to those on temporary layoff, or those quitting voluntarily, or those just entering or re-entering the workforce). Over the last year, the number of unemployed is up 5.4 million; 4.4 million of those are permanent job losers.

Although there were some encouraging signs in the report, they’re mostly of the less bad rather than the actively good variety. Forward-looking components like temp and retail employment suggest we’re in for more of the same (that is, more less bad but not yet good) for some time to come, even if GDP growth turns up in the next quarter or two.

And the longer-term picture remains horrible. Total job losses in the recession are now almost 7 million, or 5.0% of total employment. (That’s the worst percentage loss of any recession since the post-World War II demobilization.) According to an IMF study, job losses in recessions caused by financial crises average 6.3%, suggesting that we’ve got another 1.7 million jobs to lose. Since we’re about 80% of the way to the average, the best you could say is that the edge of the woods is coming into view.

Share this: