OWS takes a walk uptown

No doubt you’ve all heard and read about the huge and wonderful Occupy Wall Street satellite rally in Times Square this afternoon.

This crowd was anything but the shiftless hippies of Ann Coulter’s imagining. I bet a lot of them were Democrats, which means that the process of productive disillusionment I’d hoped for in the summer of 2008 is finally kicking into gear, after a long delay:

Enough critique; the dialectic demands something constructive to induce some forward motion. There’s no doubt that Obamalust does embody some phantasmic longing for a better world—more peaceful, egalitarian, and humane. He’ll deliver little of that—but there’s evidence of some admirable popular desires behind the crush. And they will inevitably be disappointed.

As this newsletter has argued for years, there’s great political potential in popular disillusionment with Democrats. The phenomenon was first diagnosed by Garry Wills in Nixon Agonistes. As Wills explained it, throughout the 1950s, left-liberals intellectuals thought that the national malaise was the fault of Eisenhower, and a Democrat would cure it. Well, they got JFK and everything still pretty much sucked, which is what gave rise to the rebellions of the 1960s (and all that excess that Obama wants to junk any remnant of). You could argue that the movements of the 1990s that culminated in Seattle were a minor rerun of this. The sense of malaise and alienation is probably stronger now than it was 50 years ago, and includes a lot more of the working class, whom Stanley Greenberg’s focus groups find to be really pissed off about the cost of living and the way the rich are lording it over the rest of us.

Never did the possibility of disappointment offer so much hope. That’s not what the candidate means by that word, but history can be a great ironist.

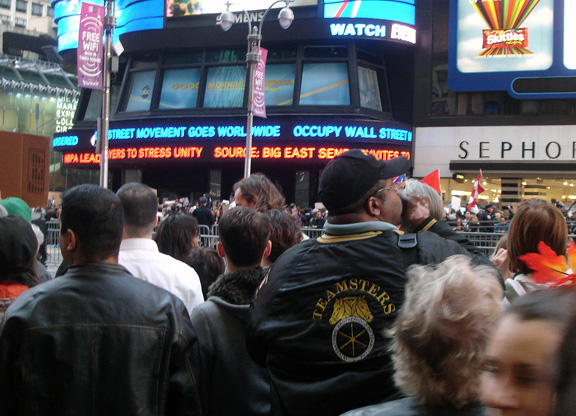

Here are some pix. It was hard to get a good perspective on the crowd from ground level, but it seemed to stretch for blocks, with people lining both sides of the Crossroads of the World.

A guy in a Teamster jacket attracted some press attention (“so you’re not all hippies,” asked the reporter). Beyond, the news zipper reports that “Occupy Wall Street Movement Goes Worldwide.”

The proceedings enjoyed a visit not only from the Comics Convention folks, but also the Z O M B I E C O N n y c crew:

Meanwhile, Beavis & Butt-head look on:

And over on 8th Ave., a delegation of 99%-ers visit Danny Meyer’s Shake Shack—where we repaired soon after young Ivan began chanting: “The people, united, will now have dinner.’

We had to get home to put our 5-year-old to bed, so we missed the part where the NYPD reportedly started arresting people. There sure were a lot of cops on the scene. Next up: Washington Square Park? That’s a city park that closes at 1 AM, so the police will have a challenge on their hands.

On the Fed (from my book Wall Street

This is the section on the Federal Reserve from my book Wall Street: How It Works and for Whom (Verso, 1997). The complete text can be downloaded here. It’s a little out of date—the Fed is more open now than it was 15 years ago, at least superficially—but it’s still fundamentally right. Two quick updates: 1) The Fed now releases summaries of its policy decisions right after the FOMC meeting. They’re somewhat sanitized, but still informative. 2) The annual profit it turns over to the Treasury has more recently been around $25 billion. Last year, it was twice that—they made money on all the crappy securities they bought during the financial crisis.

The most important government agency in the realm of money is undoubtedly the Federal Reserve. If something as decentered as a financial system has a center, it’s the central bank, and since the dollar remains the world’s central currency, the Fed is the most important of all central banks. All eyes are on it, and the tone of both financial and real business is heavily dependent on its stance. When a central bank is in an expansive mood, finance bubbles; when it’s tight, things sag.

The Federal Reserve is a study in how money and the monied constitute themselves politically. Ironically, though it’s now an anathema to populists of the left and right, its creation perversely fulfilled one of the demands of 19th century populists: for an “elastic” currency — one administered by the government that could provide emergency credit when a financial implosion seemed imminent — as an alternative to the inflexibility of the gold standard. Instead of becoming the flexible, even indulgent institution the populists dreamed of, the Fed quickly evolved into Wall Street’s very own fourth branch of government (Greider 1987, chap. 8).

Despite a couple of attempts in the early and mid-19th century to create an American central bank, they were allowed to die because of Jeffersonian–Jacksonian objections to concentrated financial power. That left the anarchic, volatile U.S. financial system without any kind of lender of last resort, but in booms all kinds of funny money passed.

Canonically, it was the panic of 1907 that led to the Fed’s creation. In the frequent panics of the late 19th century, a cabal of New York bankers would typically band together to organize lifeboat operations in emergencies; in the panic of 1895, J.P. Morgan and his cronies bailed out the U.S. Treasury itself with an emergency loan of gold. The panic of 1907, however, proved too much for these private arrangements; that time, the Treasury had to be called in to bail out the cabal. After that brush with disaster, Wall Street and its friends in Washington came around to thinking that the U.S. could go no longer without a central bank (ibid., chap. 9; Carosso 1987, pp. 535–549).

Gabriel Kolko (1963) traced the loss of the Wall Street circle’s power to several things — the aging of personalities like Morgan and Stillman (the Rockefeller representative); the growth of the economy and financial markets, and the evolution of financial centers outside New York; and the shift of industry towards internal finance, which lessened Wall Street’s influence. The loss of raw financial power, however, was compensated for by the creation of the Fed, an institution that has been dominated by Wall Street since its birth in 1913. To Kolko, the Fed was an example of an interest group using the state to reverse its fading market fortunes. This line resonates in populist discourse today.

That canonical story, however, doesn’t comport with the convincing evidence massed by James Livingston (1986). To Livingston, the struggle for a U.S. central bank had a much longer history, and one central to the creation of the modern corporate–Wall Street ruling class beginning in the 1890s. Livingston showed that the campaign for a more rational system of money and credit was not a movement of Wall Street vs. industry or regional finance, but a broad movement of elite bankers and the managers of the new corporations as well as academics and business journalists. The emergence of the Fed was the culmination of attempts to define a standard of value that began in the 1890s with the emergence of the modern professionally managed corporation owned not by its managers but by dispersed public shareholders.

Though the U.S. had become a national market deeply involved in global trade and finance in the decades following the Civil War, in the early 1890s it was still dominated by small producers and banks. As any Marxian or Keynesian crisis theorist can tell you, the separation of purchase and sale is one of the great flashpoints of capitalism; an expected sale that goes unmade can drive a capitalist under, and unravel a chain of financial commitments. Multiply that by a thousand or two and you have great potential for mischief. This is one reason the last third of the 19th century was characterized by violent booms and busts, in nearly equal measure, since almost half the period was one of panic and depression. In panics, the thousands of decentralized banks would hoard reserves, thus starving the system for liquidity precisely at the moment it was most badly needed. But the up cycles were also extraordinary, powered by loose credit and kinky currencies (like privately issued banknotes). There was no central standard of value, unlike the way we think of assets of all kinds, from cash to inverse floaters, as denominated in the same fundamental unit, the dollar. “Progressive” corporate thought, which had mastered the rhetoric of modernization, wanted a central bank that would control inflationary finance on the upswing — which in the mind of larger interests, meant keeping small operators from “overinvesting” and laying the groundwork for a deflationary panic — and extend crucial support in a crunch.

Trusts were one attempt by leading industrialists and bankers to manage the system’s instabilities, but those were prohibited by the Sherman Act of 1890. The corporation, argued Livingston, was a response to the outlawing of trusts. By internalizing lots of the the competitive system’s gaps — by bringing more transactions within the same institutional walls — corporations greatly stabilized the economy.

With the emergence of the modern firm at the turn of the century came a broader rethink of the business system. Writing in 1905, Charles Conant, a celebrity banker–intellectual, explicitly cited Marx (and anticipated Keynes) in emphasizing that the presence of money as a store of value, the possibility of keeping wealth in financial form rather than spending it promptly on commodities, always introduces the possibility of crisis. In other words, the possibility asserted by Marx but denied by classical economics, the possibility of an excess of capital lacking a profitable investment outlet, and an excess of goods that couldn’t be sold profitably on the open market, had proved all too real in practice. A system for regulating credit was essential — one that while operating through the state would be taken out of politics; the regulation of money and credit would be turned over to “experts,” that is, creditors, industrialists, and technocrats who thought like them.

The struggle around the definition of money, Livingston showed, marked the emergence of corporate and Wall Street bigwigs as a true ruling class: energized, confident, highly conscious of its mission — capable of promoting its case to a broader public using PR and friendly expertise, and to Congress with deft lobbying. Universities became rich sources of expertise for the new class, and they endowed institutes and foundations to act as a marketing and distribution mechanism for the new ideas.

The fight for sound money was also consciously exapnsive, even imperial; the economic theory of the day held that chronic oversupplies of capital and goods could be alleviated by conquering foreign markets. Big business managers with global ambitions wanted their bankers to be international, and wanted the dollar to be firm against the British pound rather than a junk currency. They wanted their paper accepted in London money markets in dollars, not pounds, and to do that required a central bank to anchor the U.S. financial system. They were also tired of the federal state being weak and small.

The panic of 1907, rather than being the catalyst it’s sometimes presented as, was taken as the “evidence that validated conclusions [the corporate–financial establishment] had already reached” (Livingston 1986, p. 172). The elite had been agitating for sterner money for a decade. The PR campaign heated up, as did the political campaign; in 1908, Congress formed a monetary commission led by the blue-chip Senator Nelson Aldrich, and the next year, the Wall Stree Journal ran a 14-part editorial on its front page arguing the case for a central bank, written by Conant. This institution would regulate “the ebb and flow of capital,” and stabilize the economy. Among the elite there was a great loss of faith in the self-regulating powers of the free market; a central bank was just the sort of expert and dispassionate intervention required to brake its frequent tendency towards derailment.

This history helps explain the essential absence of a finance–industry split, minor family quarrels excepted, over central bank policy in the U.S. and elswhere. There was remarkable regional and sectoral agreement on the need to rationalize the banking system, both for reasons of stabilizing the economy and to promote overseas commercial and imperial interests.

This history also helps explain populist thinking in the U.S. today, with a similar analysis often shared by left and right, greens and libertarians. Their opposition to central banks, centralizing corporations, and global entaglements in favor of a decentered, small-scale system reflects the historical processes by which these modern institutions formed each other. They typically forget the volatile, panic-ridden history of the late 19th century in their dreams of simpler times.

From its founding, the Fed has consisted of twelve district banks scattered around the country — a concession to the decentralized traditions of American finance and politics — and a central governing board in Washington. The district Federal Reserve banks are technically owned by the private banks in their regions, which choose six of each district bank’s nine directors. Of the New York district’s nine serving in 1996, three were bankers (from the Bank of New York, and smallish banks on Long Island and in Buffalo); two were CEOs of giant companies (AT&T and Pfizer). The balance: conservative New York City teachers’ union leader, Sandra Feldman; private investor John Whitehead, formerly of Goldman, Sachs and the Carter cabinet; investment banker Pete Peterson of The Blackstone Group, formerly of the Nixon administration, and sworn enemy of Social Security; and the head of a giant pension fund, Thomas Jones of TIAA–CREF. Recent alums include the CEO of a large insurance company, a small business-owner, and the head of an elite foundation. Of all these, only two were outside the Big Business/Big Finance orbit — three if you’re generous, and want to count the foundation executive, but foundations have big financial holdings, and are politically and socially intimate with the corporate class. So while the Federal Reserve System is technically an agency of the federal government, an important part of the system is directly owned and controlled by private interests.

Despite the original decentralizing intent of the district structure, power quickly gravitated toward two centers — Washington, where the Fed is headquartered, and New York, the site of the most important of the regional banks because of its location just blocks from Wall Street. Day-to-day monetary policy is carried out, based on broad instructions from Washington, at the New York Fed’s trading desk. The system’s executive body is a Board of Governors, consisting of seven members nominated by the President and confirmed by the Senate, who serve for a term of fourteen years. That long term is supposed to insulate the governors from political pressures; in reality, it insulates them almost completely from anything like democratic accountability. From the seven board members, the President nominates, subject to Senate confirmation, a chair and a vice chair, who serve four-year terms. The board has in practice been pretty well dominated by the chair; after leaving the vice-chairship in 1996, Alan Blinder complained publicly about his difficulty in even getting information out of the staff economists. From the chair down to the vice presidents and directors of the district banks, the Fed’s senior staff is overwhelmingly male, white and privileged (Mfume 1993).

Unlike ordinary government agencies, the Fed is entirely self-financing; it need never go to Congress, hat in hand. Almost all its income comes from its portfolio of nearly $400 billion in U.S. Treasury securities. It’s not a difficult trick to build up a huge piggy bank when you can buy bonds with money you create out of thin air, as the Fed does. In fact, at the end of every year, the Fed returns a profit of $15–20 billion to the Treasury — after deducting, of course, what it considers to be reasonable expenses. Salaries are far more generous, and working conditions far more comfortable, than in more mundane branches of government — and there’s not much that mere civilians can do to challenge its definition of reasonableness.

Monetary policy is set by a Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), which consists of the seven governors plus five of the district bank presidents, who serve in rotation —five of the twelve votes are cast by the heads of institutions owned by commercial banks, a very strange feature in a nominally democratic government. Imagine the outcry if almost half the seats on the National Labor Relations Board were reserved for staunch unionists.

The FOMC meets in secret every five to eight weeks to set the tone of monetary policy — restrictive, accommodative or neutral, in Fed jargon. Until very recently, the committee didn’t announce policy decisions until six to eight weeks after they’d been made. In a departure from almost eighty years of history, the sequence of tightenings started in February 1994 were announced immediately, a frank attempt to steal some of the populist reformers’ thunder. Until early 1995, those reformers were led by Texas Rep. Henry Gonzalez, who spent his few years as chair of the House Banking Committee deliciously torturing the Fed in every way possible. The threat of subpoenas from Gonzalez caused a sudden bout of recovered memory syndrome at the Fed; for 17 years, it had denied that it even took detailed minutes at FOMC meetings; in fact, it had been taping and transcribing them all along. The Republican takeover of Congress in 1994, however, ended Gonzalez’ reign of terror.

Still, despite this whiff of glasnost, the Fed remains an intensely secretive institution. This opaqueness has spawned an entire Fed-watching industry, a trade reminiscent of Kremlinology, in which every institutional twitch is scrutinized for clues to policy changes. One of the sacred moments in Wall Street life is “Fed time,” just before noon every day, when the central bank intervenes or doesn’t intervene in the market (by buying Treasury securities in the open market to inject liquidity into the banking system, or selling them to drain liquidity). In the days before the Fed announced policy changes immediately, these interventions or their lack — whether they were more or less generous than Fed watchers had been expecting — were read as signs of a possible change in policy. Fed watchers, many of them recent alumni of the central bank, “earn” salaries well into the six figures for such work; greater openness at the Fed would reduce their importance, if not put them out of business, a rare form of unemployment that would be entirely welcome. The Fed also manipulates the media ably; reporters, eager for a leak from a central bank insider, will print anything whispered in their ears, whether or not it’s true — leaks sometimes designed to mislead or enlighten the markets, and other times the product of some internal struggle.

Even though FOMC members would no doubt invent all sorts of clever euphemisms to express the dangers of excessively low unemployment, televising the FOMC’s proceedings on C-SPAN would still provide an enlightening glimpse into the mentality of power.

Jacobin OWS correction

Bluestockings is at 172 Allen St, not 72 as I said earlier. 172! At least I got the time right: it’s at 7.

Jacobin event tonight in NYC

A reminder—I’m part of a panel organized by the excellent posse at Jacobin on Occupy Wall Street, along with Jodi Dean, Malcolm Harris, Natasha Lennard, and Chris Maisano.

Bluestockings

172 Allen St (Stanton–Rivington)

Manhattan

7 PM

Likely to be crowded, and Bluestockings is small—so get there early!

On OWS and the Fed

[I haven’t been posting my radio commentaries here in a while. Here’s some of October 8’s.]

Rethinking OWS

Turning to larger issues, not only does Occupy Wall Street continue, it’s grown in numbers and prominence—several major unions marched in solidarity earlier this week in Lower Manhattan—and it’s spreading around the country. It’s focusing attention on issues of inequality and exploitation in a way we haven’t seen in ages. And Democratic politicians are looking pressured to say sympathetic things—though I suspect they’re just looking to take advantage of the thing for their own electoral reasons. But, as my wife Liza Featherstone remarked the other night, at no time in her life (she’s 42) have politicians felt compelled to co-opt a movement on the left. This is extremely good news.

I’ve also rethought some of my earlier skepticism about where all this will lead. Last week, after professing my love for the protesters—a love that has only deepened—I said that they need to develop some organization and demands. On further reflection, I don’t think that’s their job as a group. Some of the individuals may do that—who knows what kinds of contacts and networks are developing and where they will go. But I think they’re now doing what they’re best at: getting a wide variety of people to think and talk about the disastrous state of the U.S. economy and our aspirations for making it better. Organization and program can be left to others. I’m full of ideas, for example, though I’m not so organized. Unions are showing signs of political life they haven’t shown in living memory. I don’t trust what Democrats are doing with this movement—even supposed good guys like Van Jones. But if they’re forced to tax millionaires to fund a jobs program, or at least say they’re into that idea, then something’s moving.

I’m also proud that my hometown is inspiring people across the country and around the world. It’s been a long time since the city of JP Morgan and Michael Bloomberg have done that. Like I said last week, who knows where this will lead—but so far, it’s leading to some good places.

On the Federal Reserve

I have noticed some strange, Ron Paul-ish stuff about the Federal Reserve around Occupy Wall Street. I do want to file a complaint about that.

The Federal Reserve is admittedly manna for conspiracists. It’s a fairly opaque institution that does work for the big guys. But it’s not their puppet exactly. A friend who spent many years at the New York branch of the Fed once told me that within the institution, the thinking is that bankers are short-sighted critters who come and go but the Fed has to do the long-term thinking for the ruling class. So it has more autonomy than the popular tales allow.

The founding of the Fed is also a great subject of mythmaking—like secret meetings involving more than a few Jews. (The conspiratorial mindset often overlaps with anti-Semitic stories about rootless cosmopolitans, their greed and scheming.) There were some secret meetings, but the creation of a central bank was a major project of the U.S. elite for decades around the turn of the 19th century into the 20th. There’s a great book on that topic by James Livingston that I urge anyone interested in the topic to read. It was a long, complex campaign, and not the task of a secret train ride to a remote island.

Although the Fed does put U.S. interests first, it is internationally minded, and consults constantly with its foreign counterparts. This is also rich soil for conspiratorial thinking—that, plus, of course the Jews. (Greenspan. Bernanke. You’d almost forget that 1980s Fed chair Paul Volcker’s middle name is Adolph.) You know the story—dastardly plots involving foreign financiers (with names like Rothschild) whose victims are good patriotic Americans. As anyone who watches the Fed closely, like me, could tell you, that’s just not the case.

And it’s tempting to see this body as controlling everything—it’s complicated and messy to think about how financial markets work, and the Fed’s relationship to those markets. Much easier to think of the Fed controlling everything. But in fact the Fed sometimes reacts to the markets, sometimes leads them, and on occasion fights with them.

In the 1980s, the Federal Reserve under Paul Volcker ran a very tight ship. It deliberately provoked a deep recession in 1981-82 by driving up interest rates toward 20% to scare the pants of the working class. It was a very successful class war from above that led to a massive upward redistribution of income. More recently, the Fed handed out massive amounts of money—I’m not citing actual figures since they’re vague and mind-boggling, but they’re very big—with no strings attached to major banks. Something like this was necessary to keep everything from going down the drain, but it didn’t have to be done so secretly and with no accountability. Banks were basically given blank checks to restore the status quo ante bustum. That’s terrible. You could say the same for the TARP bailout—massive giveaways with no accountability or restrictions. This is all odious.

But more recently, Fed chair Ben Bernanke has been about the only major policymaker in the world pushing for more stimulus for the U.S. economy. He’s not a partisan of austerity, like the Republicans or much of the pundit class. For this he’s earned some criticisms on the right. The right would be happy to let things go down to prove a point. They think we need a “purgation.” I was recently on a panel with a Fed-hating libertarian who invoked the concept of “purgatory,” as if we’ve all sinned. But that would create far more misery than we know now.

There’s a video (#OWS Protester Nails It! Federal Reserve) of an Occupy Wall Street protester calling for an end to the Fed and urging a vote for Ron Paul. It, and the comments, are straight out of the right-wing critique of the Fed. I’ve seen signs calling for that around the occupation. This is bad news. Ron Paul has a coherent political philosophy. He’s a libertarian. He may hate imperial war, but he also hates Social Security and Medicare. The reason he wants to end the Fed is that he wants to get the state out of the money business and return to a 19th century gold standard. A gold standard is painfully austere. The gold supply increases by less than 2% a year. That means tremendous pressure on average incomes. It’s great if you’re a big bondholder, but hell if you’re a regular person. When we were on a gold standard in the 19th century we had frequent panics, crises, and depressions. Almost half of the last three decades of the 19th century was spent in recession or depression. It put both rural farmers and urban workers through the wringer.

We need to democratize the Fed, open it up, and subject money to more humane and less upper-class-friendly regulation. But let’s not sign on with Ron Paul, please. And let’s not join with the simple-minded right-wing critique that blames all of capitalism’s systemic problems on government institutions.

The Wall Street worldview

Wall Street’s favorite economist, Ed Hyman, likes to annotate headlines and news snippets. In today’s morning report, he groups some under “depressing” and others under “encouraging.”

Depressing

Unions Join Wall St Protest (NYT)

Senate Democrats proposed a 5% surtax on incomes over $1m (WSJ)Encouraging

Merkel Ready to Aid Banks (IBD)

The BoE expanded its bond-purchase plan to $420b from $300b (Bloomberg)

IMF Considers Plan to Purchase European Bonds (WSJ)

Gotta love that state when it supports The Market, eh?

Jodi Dean on phases of struggle

[posted to Facebook]

Ideological notes

I know this will prompt more rebukes for trying to impose an anachronistic old left on the spontaneously new, but someone’s got to do it.

I read this quote in the New York Times the other day. I know that that may not be the go-to medium for reports on Occupy Wall Street, but it’s not unrepresentative of some of the things I’ve seen and heard first hand from that quarter:

“This is not about left versus right,” said the photographer, Christopher Walsh, 25, from Bushwick, Brooklyn. “It’s about hierarchy versus autonomy.”

Autonomy in this context sounds like a hipster version of bourgeois individualism. I’ve also seen a bit of Ron Paul-ish “end the Fed” stuff around OWS, which is a topic in itself, something I’ll take up in the near future. But I don’t want to get that wonky just now. I just want to make a simple point. Occupy Wall Street is hardly about autonomy. It’s about living out solidarity and about attracting people to a movement. They’re living a collectivity, even if they’re not articulating it that way.

I suspect the problem is that three decades of neoliberalism have destroyed any available vocabulary for solidarity. My guess is that most of the people in Zuccotti Park were born after Thatcher and Reagan took office. There’s no such thing as society, as the Lady said. But there is, and we need more of it.

Maybe 99% is a bit much, but…

The last day or two I’ve been seeing some complaints that the chant of the Occupy Wall Street protesters that “We are the 99%” casts the net too widely, effacing all kinds of class, race, and gender distinctions. Well, yes, probably so. But I still find it cheering.

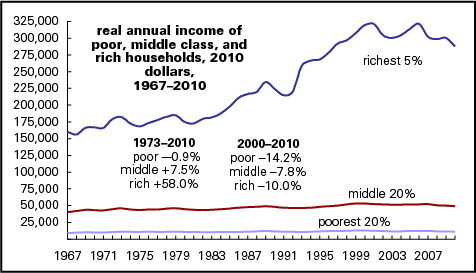

It is a fact that over the last couple of decades, much of the growth in total income in the U.S. has gone to the upper reaches of society. For example, based on Census data, between 1982 and 2010, the richest fifth of society have claimed a little over half of the increase in total personal income; the top 5%, nearly a quarter the gain. The bottom 60% of society, though, has gotten less than a quarter. And, for a number of reasons, the Census figures seriously underestimate the action at the very top. (For more, see the forthcoming LBO, now in prep.) Using data compiled by the economists Emmanuel Saez and Thomas Piketty from IRS records, we can estimate that the top 1% took in a quarter of the income gain between 1982 and 2008. The bottom 90%, though, only took in 40% of the gain. (1982, by the way, is when the great bull market in stocks took off, corporate profitability began a long upsurge, and the Roaring Eighties really began.) And the further you go down the ladder within the bottom 90%, the smaller the gains.

Looked at another way, here are two graphs of average incomes, adjusted for inflation, the first from the Census data:

and this from the Piketty–Saez data (the line marked “99” means the income of those richer than 99% of society, and “0–90,” the average for the bottom 90%):

Since percentiles may be a bit abstract, here’s something more concrete: the income in 2008 at the 99th percentile was $368,238; the average for the bottom 90%, was $31,244. The disparity would be even greater if we looked at only the top 0.1%—and even greater at the top 0.01%. And if we looked at only the Forbes 400, their line would probably blow the top off your computer monitor.

Yes, so the 99% thing is an exaggeration. People at the 90th percentile have done pretty well—not as well as the 99th, but a lot better than the 80th, 50th, or 20th. With few exceptions, the further down you go, the worse you’ve done.

What’s refreshing, though, about the 99% chant is that it strives towards something like universality. For the last few decades—pretty much those in which the rich have gotten a lot richer—many of us have been obsessed with slicing society into finer and finer pieces. That’s far from a useless effort; many stories are hidden behind averages, and we’ve learned that there’s a lot of particularity behind abstractions like the “working class.” This experience has given us the chance, as Kim Moody put it in a 1996 New Left Review article, “to get the active concept of class right this time,” in contrast with the 1930s or 1960s.

So yeah, the 99% thing may be a stretch; maybe 80% is more like it, and even so there would be a lot of tensions within such a large population. (Keeping those under cover is one of the advantages of not articulating an agenda, though that blessed state can’t go on forever.) But 99% is catchy, and it can lead in very fruitful directions.

New radio product

Just posted to my radio archives:

October 1, 2011 Corey Robin, political scientist at Brooklyn College and author of The Reactionary Mind, on how the right thinks

Bloomberg sheds a tear for bankers, makes up bogus numbers

Asked to comment on the Occupy Wall Street protests, plutocrat Mayor Michael Bloomberg—#12 on the Forbes 400, net worth almost $20 billion—painted a heart-rending portrait of suffering bankers:

The protesters are protesting against people who make $40-50,000 a year and are struggling to make ends meet. That’s the bottom line.Those are the people that work on Wall Street or on the finance sector.

We need to be nice to them, Bloomberg continued, so they’ll make loans and help the economy recover. No need to dwell on the past—let’s move forward.

Fact-checking the Mayor, who is far from a stupid or ignorant man: According to the Bureau of Economic Analysis, the agency that produces the GDP statistics, the average salary in the finance and insurance sector was $88,118 last year. In the “securities, commodity contracts, and investments” sector, which is what people mean when they say “Wall Street,” the average salary was $204,539. That’s four times the national average. Struggling indeed.

(The ThinkProgress reporter in the linked article only got some spotty and misleading numbers. For the BEA originals, go here: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. Click on the “Begin using the data” button, choose section 6, and then choose table 6.6D. There’s no direct link to that table, thus the roundabout route.)

Shaking a fist at the NYPD

There was a demonstration this afternoon organized by my friends Penny Lewis and Alex Vitale, among others, in front of NYPD headquarters to object to the nasty treatment of the Occupy Wall Street protesters and years of repression of dissent in what was once a rambunctious city. (Here’s the event’s Facebook page.) Since Giuliani and continuing through Bloomberg, the cops have used “quality of life” pretexts—keep the traffic moving!—to limit marches. And they’ve spied on organizers, arrested protesters en masse, and generally made peaceful dissent very difficult. The fact that a senior cop was videotaped pepper-spraying penned-in people who’d done nothing violent now seems to have the force on the defensive, thank god. But the longer the OWS protest goes on, the risk of more brutality rises.

When I got there, about a half hour after scheduled starting time, Penny was addressing a small crowd.

It was a spirited gathering, and Penny was terrific, but I was a little worried that the demo would turn out to be an anticlimax. Still, the cops were ready—on the ground

and in the air.

Any gathering in New York is guaranteed to have an aerial audience like this—there were at least three helicopters hovering overhead.

But then there was kerfuffle at the entrance to Police Plaza (through the Manhattan Municipal Building, a borough hall on a rather grand scale). People began chanting “Let them in.” I was too far away to see if the police were blocking the way, but if they were, they didn’t for long as a large throng of reinforcements came in from the main OWS site at Zuccotti Park.

Soon, Police Plaza was filled with a giant, noisy crowd. This is what the area where the white-shirted cops were standing in the photo above looked like about seven minutes after that photo was taken.

(That’s Rev. Billy with the preacherly pose in the center, and Greg Grandin, the Latin America scholar at NYU, in the green shirt, front right.)

Still, despite the size of the crowd, and the fact that there was no permit for the demo, the cops just stood back. There was a line of them in front of the entrance to police HQ, but they just stood around. Earlier, they’d looked a bit taken aback by the influx. Who knows what they’ll do if all this continues, but for now, free speech had the upper hand in lower Manhattan.

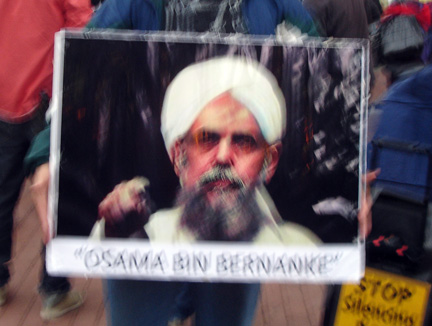

There were union signs and the usual crop of protest slogans, but there was also one odd image crafted presumably by a critic of quantitative easing:

But that was just an amusing curiosity. The overwhelming tone was spirited, determined, and thoroughly inspiring. As I’ve said before, who knows where this is going, but right now it’s exciting. It didn’t hurt that this particular demo had a very clear message—stop beating people and let people speak freely. But with the original OWS encampment persisting, and cities across the country joining in, I thought of Wallace Stevens’ line about searching “a possible for its possibleness.”

The Occupy Wall Street non-agenda

I’m not here to disparage Occupy Wall Street; I admire the tenacity and nerve of the occupiers, and hope it grows. But I’m both curious and frustrated by the inability of the organizers, whoever they are exactly, or the participants, an endlessly shifting population, to say clearly and succinctly why they’re there. Yes, I know that certain liberals are using that to malign the protesters. I’m not. I desperately hope that something comes of this. But there’s a serious problem with this speechlessness.

Certainly the location of the protest is a statement, but when it comes to words, there’s a strange silence—or prolixity, which in this case, amounts to pretty much the same thing. Why can’t they say something like this? “These gangsters have too much money. They wrecked the economy, got bailed out, and are back to business as usual. We need jobs, schools, health care, and clean energy. Let’s take their money to pay for them.” The potential constituency for that agenda is huge.

Why instead do we see sprawling things like this (A Message From Occupied Wall Street), eleven demands, each identified as the one demand? Or this: The demand is a process? A process that includes this voting ritual: Select Below and Vote to Include in the Official Demands for #Occupy Wall Street.

Why the emphasis on multiplicity and process? I think it’s a living instance of a problem that Jodi Dean identified last November—a paralysis of the will, though one disguised as a set of principles:

Once the New Left delegitimized the old one, it made political will into an offense, a crime with all sorts of different elements:

- taking the place or speaking for another (the crime of representation);

- obscuring other crimes and harms (the crime of exclusion);

- judging, condemning, and failing to acknowledge the large terrain of complicating factors necessarily disrupting simple notions of agency (the crime of dogmatism);

- employing dangerous totalizing fantasies that posit an end of history and lead to genocidal adventurism (the crime of utopianism or, as Mark Fisher so persuasively demonstrates, of adopting a fundamentally irrational and unrealistic stance, of failing to concede to the reality of capitalism).

An agenda—and an organization, and some kind of leadership that could speak and be spoken to—would violate these rules. Distilling things down to a simple set of demands would be hierarchical, and commit a crime of exclusion. Having an organization with some sort of leadership would force some to speak for others, the crime of representation.

But without those things, as Jodi says, there can be no politics. “It is instead an ethics. Is it any surprise, then, that under neoliberalism ostensible leftists spend countless hours and pages and keystrokes elaborating ethics? The ethics of this or the ethics of that, fundamentally personal and individual approaches that obscure and deny the systems and structures in which they are embedded?”

Occupiers: I love you, I’m glad you’re there, the people I talked to were inspiring—but you really have to move beyond this. Neoliberalism couldn’t ask for a less threatening kind of dissent.

1930s phantasms from the right: how to make up stories with numbers

Economists Harold Cole and Lee Ohanian have a piece in the Wall Street Journal that deserves a prize for the devious use of statistics. They want to argue that fiscal stimulus is bad, and the New Deal only made the Depression worse. This is a familiar argument on the right—and I even heard it once from a Marxist economist—but it’s just not true.

Here’s the prize-eligible statement:

But boosting aggregate demand did not end the Great Depression. After the initial stock market crash of 1929 and subsequent economic plunge, a recovery began in the summer of 1932, well before the New Deal. The Federal Reserve Board’s Index of Industrial production rose nearly 50% between the Depression’s trough of July 1932 and June 1933. This was a period of significant deflation. Inflation began after June 1933, following the demise of the gold standard. Despite higher aggregate demand, industrial production was roughly flat over the following year.

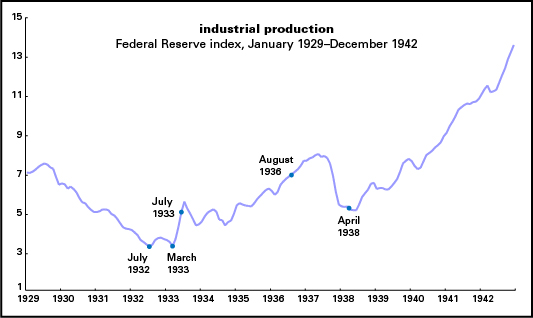

Here’s a graph of the Fed’s industrial production index for the period:

Crucial months are marked. July 1932 is the phantasmic trough of the recession named by Cole and Ohanian. Note that there was little recovery at all in industrial production between July and March 1933—the official Depression trough, so designated by the arbiter of these things, the National Bureau of Economic Research. March 1933 also the month that Roosevelt took office and declared a bank holiday, ending a four-year run on the banks. A month later, he severed the dollar’s link to gold and made it clear that the U.S. government was determined to put an end to deflation. Though the alphabet soup of New Deal programs was yet to come, the break with previous orthodox economic policy was clear. And industrial production began a sharp recovery.

August 1936 [note: I’d originally, and wrongly, said April 1936] is marked because that’s when the Fed began to double reserve requirements for banks, a policy move that Milton Friedman indicted for causing the relapse of Depression in 1937. (Though widely accepted, that argument has been disputed in a paper by Charles Calomiris et al, but that’s not relevant to the politics of this, given Friedman’s right-wing credentials.) Keynesians have also pointed to a marked tightening of fiscal policy, announced in 1936, for the return to slump.

In other words, stimulus worked as advertised, and so did austerity.

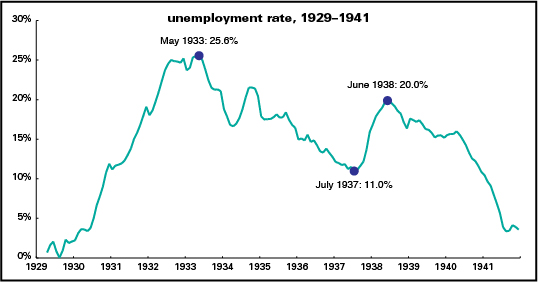

Cole and Ohanian grudgingly concede that unemployment declined between 1933 and 1937, but they don’t let on by how much. Here’s the history, from the NBER (official BLS monthly unemployment stats don’t begin until 1948):

The unemployment rate fell by more than half between the May 1933 peak (two months after FDR took office) and the July 1937 low. They want to minimize this, but a decline of that magnitude is remarkable.

They also want to minimize the broad economic recovery that occurred in the mid-1930s. But real GDP rose 30% between 1933 and 1937, an average of almost 7% a year. Again, nothing to sneeze at.

As Irving Fisher wrote in his classic paper, “The Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions”:

Those who imagine that Roosevelt’s avowed reflation is not the cause of our recovery but that we had “reached the bottom anyway” are very much mistaken…. According to all the evidence, debt and deflation, which had wrought havoc up to March 4, 1933, were then stronger than ever, and let alone would have wreaked greater wreckage than ever, after March 4. Had no “artificial respiration” been applied, we would soon have seen general bankruptcies of the mortgage guarantee companies, savings banks, life insurance companies, railways, municipalities, and states. By that time the Federal Government would probably have become unable to pay its bills without resort to the printing press, which would itself have been a very belated and unfortunate case of artificial respiration. If even then our rulers should still have insisted on “leaving recovery to nature” and should still have refused to inflate in any way, should vainly have tried to balance the budget and discharge more government employees, to raise taxes, to float, or try to float, more loans, they would soon have ceased to be our rulers. For we would have insolvency of our national government itself, and probably some form of political revolution without waiting for the next legal election.

If you think stimulus is a bad idea, make that argument. But don’t make up stuff about the past.

Visiting the occupiers of Wall Street

Occupying Wall Street

We—my wife Liza Featherstone and son Ivan Henwood and I—paid a visit to the Occupy Wall Street protest yesterday afternoon. Here’s an illustrated report. I also did a segment for my radio show. Audio for that is at the bottom of this entry.

The big media have largely ignored the OWS protest (though if you’re part of a certain kind of network on Facebook, you can’t miss it). Called first by Adbusters with only the most minimal agenda, it’s taking on a life of its own, as people trickle in from all over. And I do mean minimal—the agenda is supposed to evolve spontaneously. When I talked with one of the organizers last week, she told me that they merely hoped “to build the new inside the shell of the old,” and though that sounds seductively wonderful, I’m not sure how robust such an approach can really be.

Or, to quote the event’s Facebook page, named in the now-ubiquitous hashtag fashion (#OCCUPYWALLSTREET):

we zero in on what our one demand will be, a demand that awakens the imagination and, if achieved, would propel us toward the radical democracy of the future

I don’t think that has Lloyd Blankfein trembling in his shoes. Not that I know what could make him tremble, aside from a few quarterly losses for Goldman.

When we got to Wall Street, a band of what appeared to be several hundred were conducting the “closing bell” march, joining in the traditional observation of the end of the trading day on the New York Stock Exchange. The dominant chant was: “Banks got bailed out, we got sold out.” Here’s glimpse of what it looked like, from the corner where George Washington was inaugurated for the first time.

It’s not often you see a quote from Ronald Reagan at an event like this, but the politics of the participants looked like a mixed bag, a topic I’ll return to.

This being New York, a healthy contingent of cops was on the scene.

At the corner of Wall and Broadway, things dispersed some, with some of the crowd (including us) heading towards the base camp, Zuccotti Park at the corner of Broadway and Liberty, not far from the “Freedom Tower” (under construction). Here’s what the park looked like from the Broadway side.

Within, one quickly encountered familiar iconography, e.g., this U.S. flag with corporate logos in place of the stars (photo by Ivan Henwood).

Posters promoting the event, exhibiting that Adbusters style that’s a reminder that Judith Butler was so right to say that you have to inhabit what you parody.

The crowd was a mix of locals and migrants. I chatted with people who’d come from Missouri and Maine to express frustration and show solidarity. (They’re on the audio segment.) The woman from Maine was unemployed for a year and willing to stay as long as anyone else is there—through January, if that’s what it takes. But I also talked with locals from Brooklyn and Queens. Onlookers and passers-by were neutral to friendly—there were no jeers except some aimed for a lone and odious anti-Semite.

A celebrity local: the original pie-wielding Yippie Aron “Pieman” Kay.

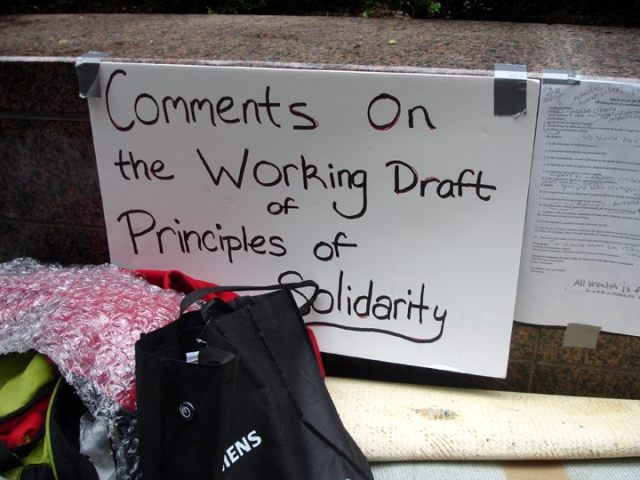

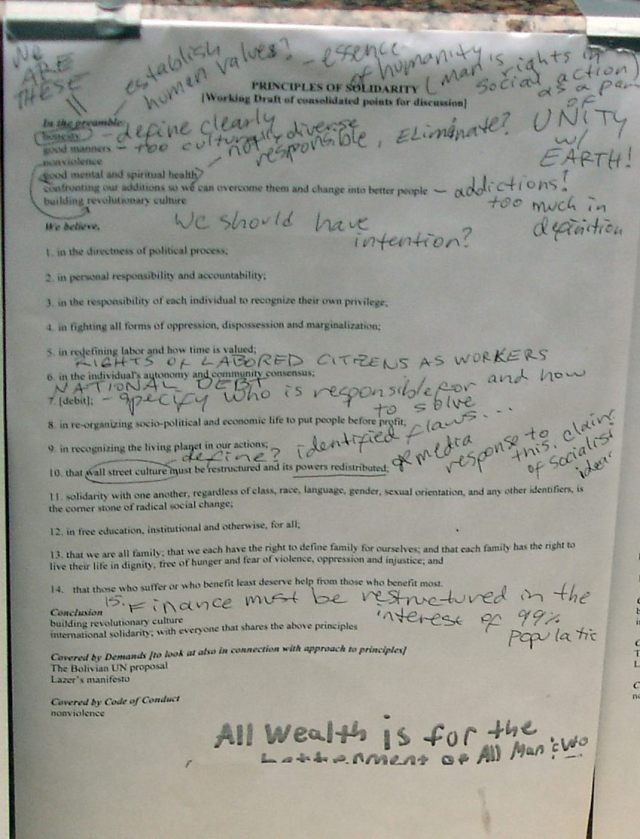

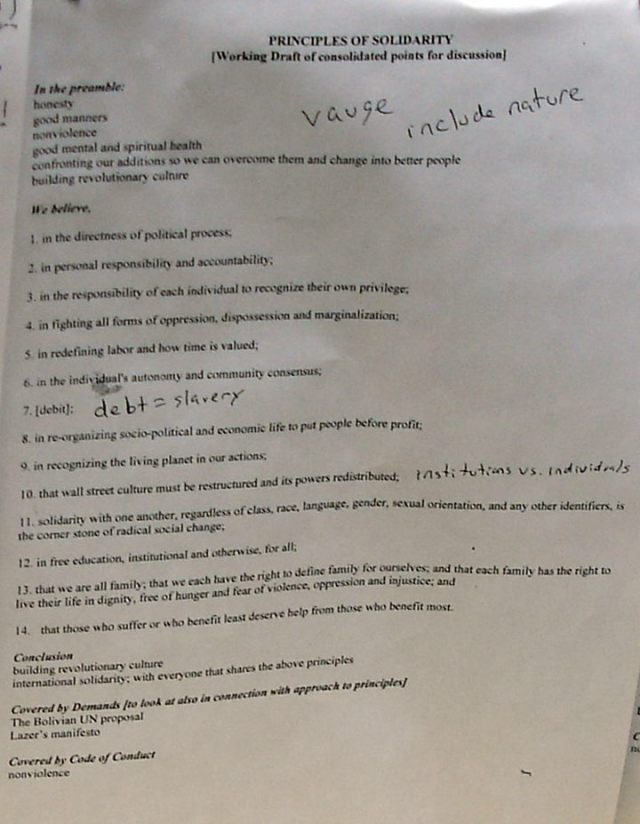

Principles were being worked on in standard “consensus” fashion, which apparently means writing comments on pages taped to a wall. (The type is readable if you click on the pix to enlarge them.)

“Vauge” indeed.

Signs were being made constantly.

I asked the guy who made the “utopian experiments” sign what he had in mind. (The interview is on the audio segment.) He said he wanted to see a rebirth of 1960s-style “intentional communities,” though more entrepreneurial this time, capable of supporting themselves through green business and cyberschemes. Aside from this apostle of green entrepreneuriship, I overheard others talking about how Wall Street stifled small business—as if small business didn’t pay worse and support more right-wing politicians than big business. It was a very mixed bag ideologically. It seems like the latest iteration of American populism, which hates Wall Street and internationalization but loves small business and the local. Of course, livestreaming the proceedings on the web (see here) depends on a huge technical infrastructure, but no one thinks about that at these events.

I was skeptical of this at first, and I still am. There’s no agenda at all. It’s mostly about process—meaning consensus. There’s no organization to speak of. But maybe people will just keep trickling in and it will grow and persist and something good could come of it. Word is that some buses will be coming in from Wisconsin soon. At some point, though, I fear the NYPD will stop putting up with a semi-permanent occupation of a small park. I hope not. But if you’re listening to this, and are in a position to head to lower Manhattan, check it out. Zuccotti Park, at the corner of Broadway and Liberty St.

Give the NYPD something to watch.

Here’s the report on the event from my radio show. For the full show, click here. This is just a six-minute excerpt.

Occupy Wall Street: audio report

All photos by Doug Henwood except the corporate logo flag, by Ivan Henwood.